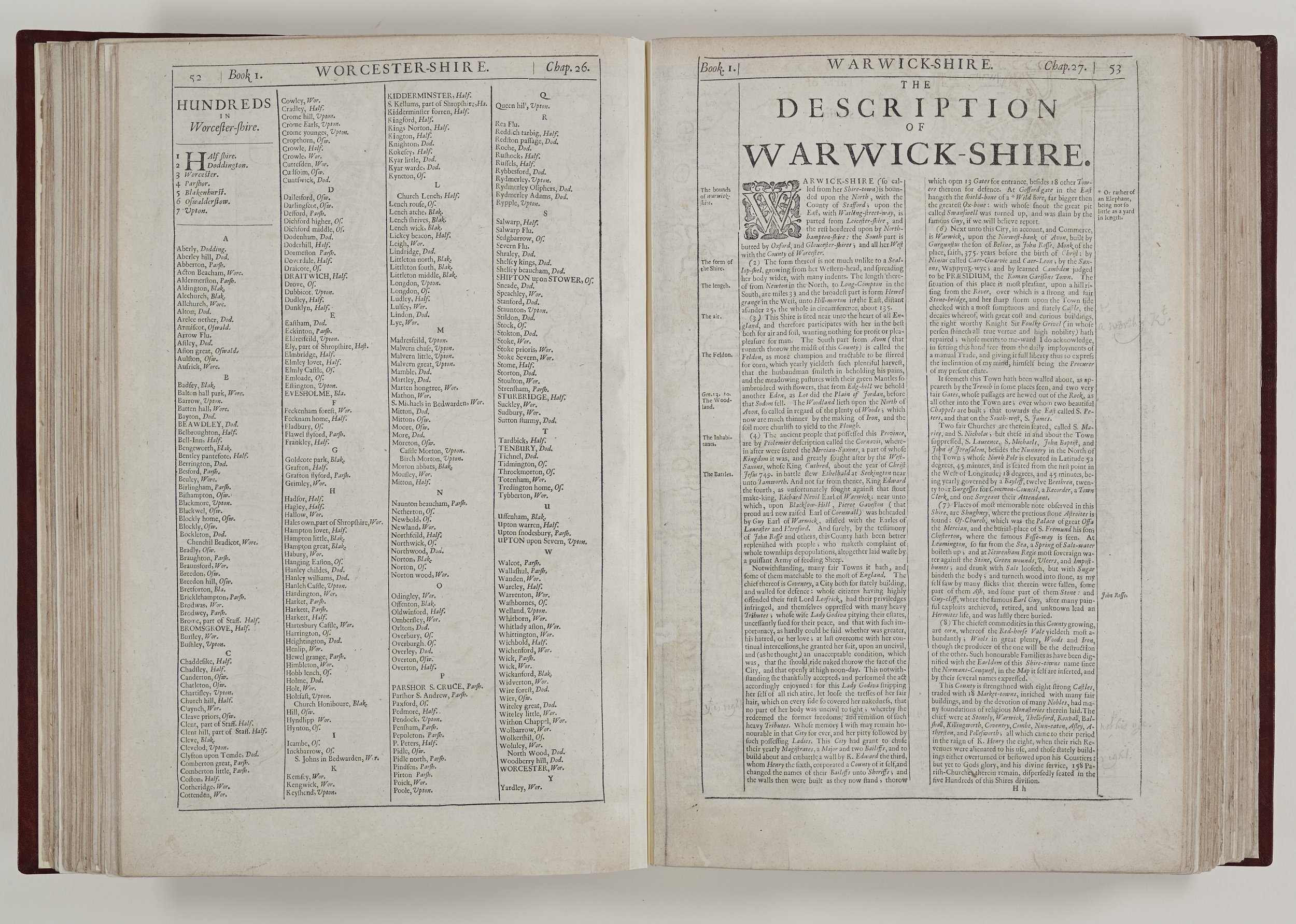

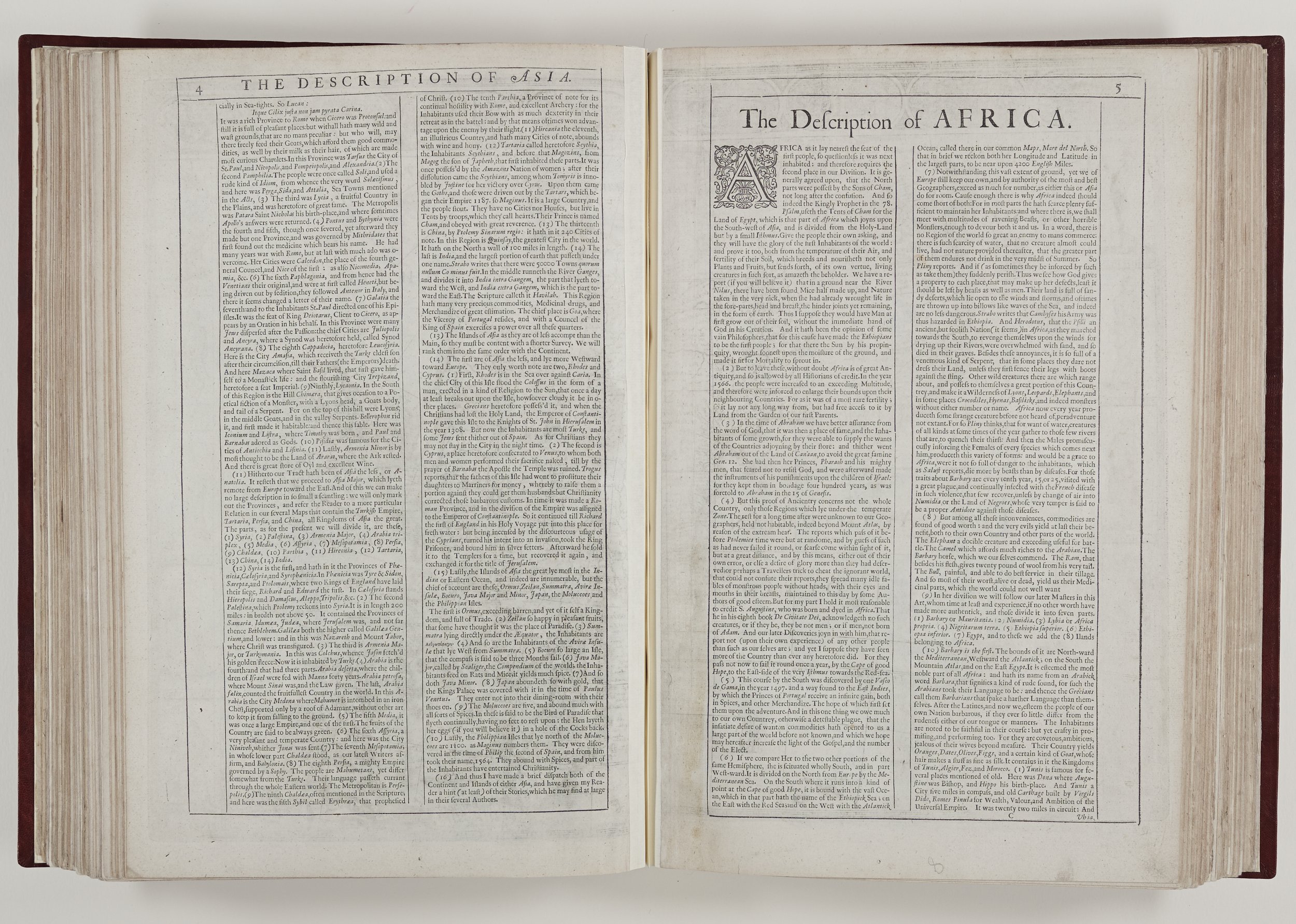

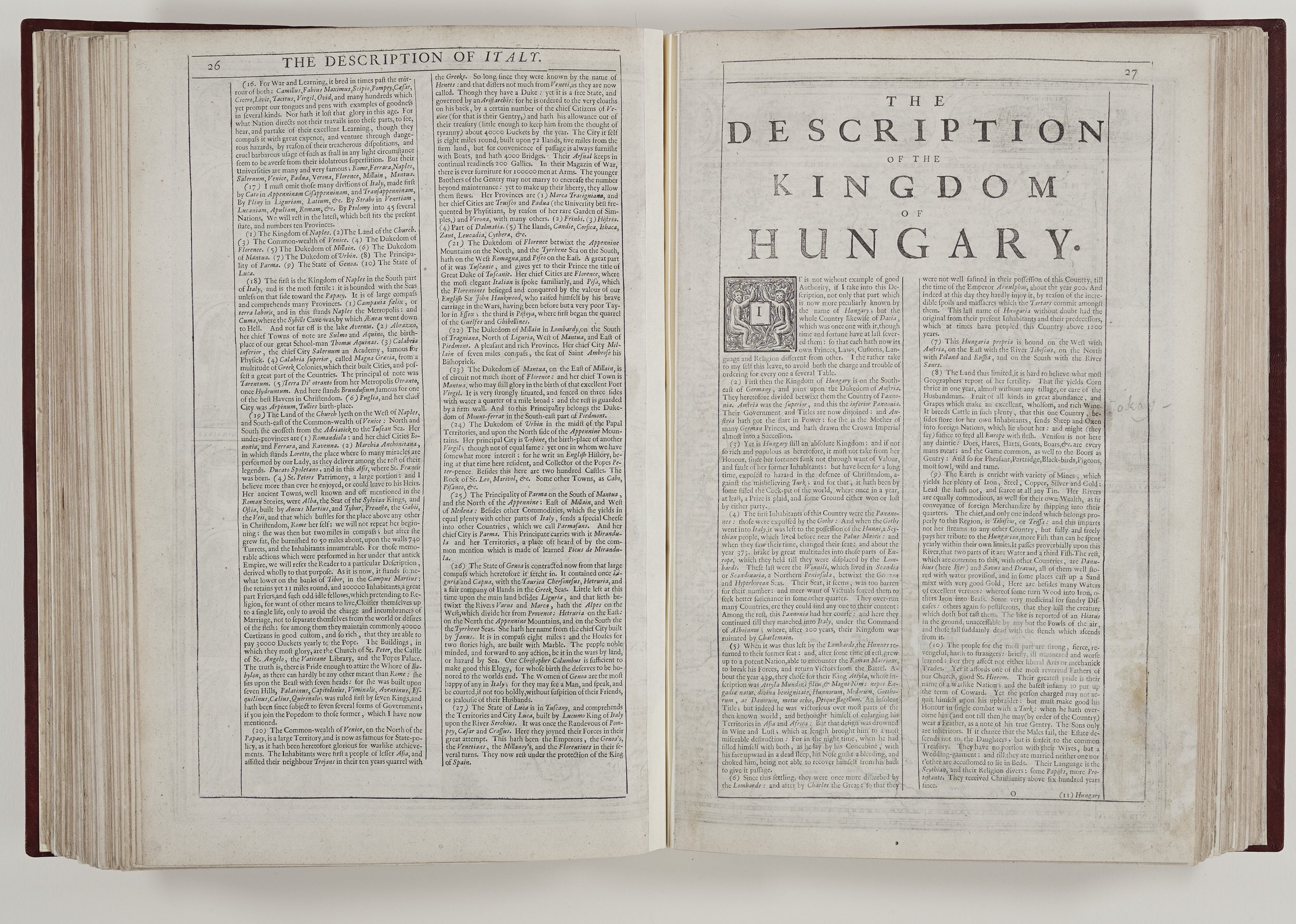

John Speed's atlas, 1676

/An Introduction to John Speed and his Theatre of the empire of Great-Britain and A prospect of the most famous parts of the World published 1676.

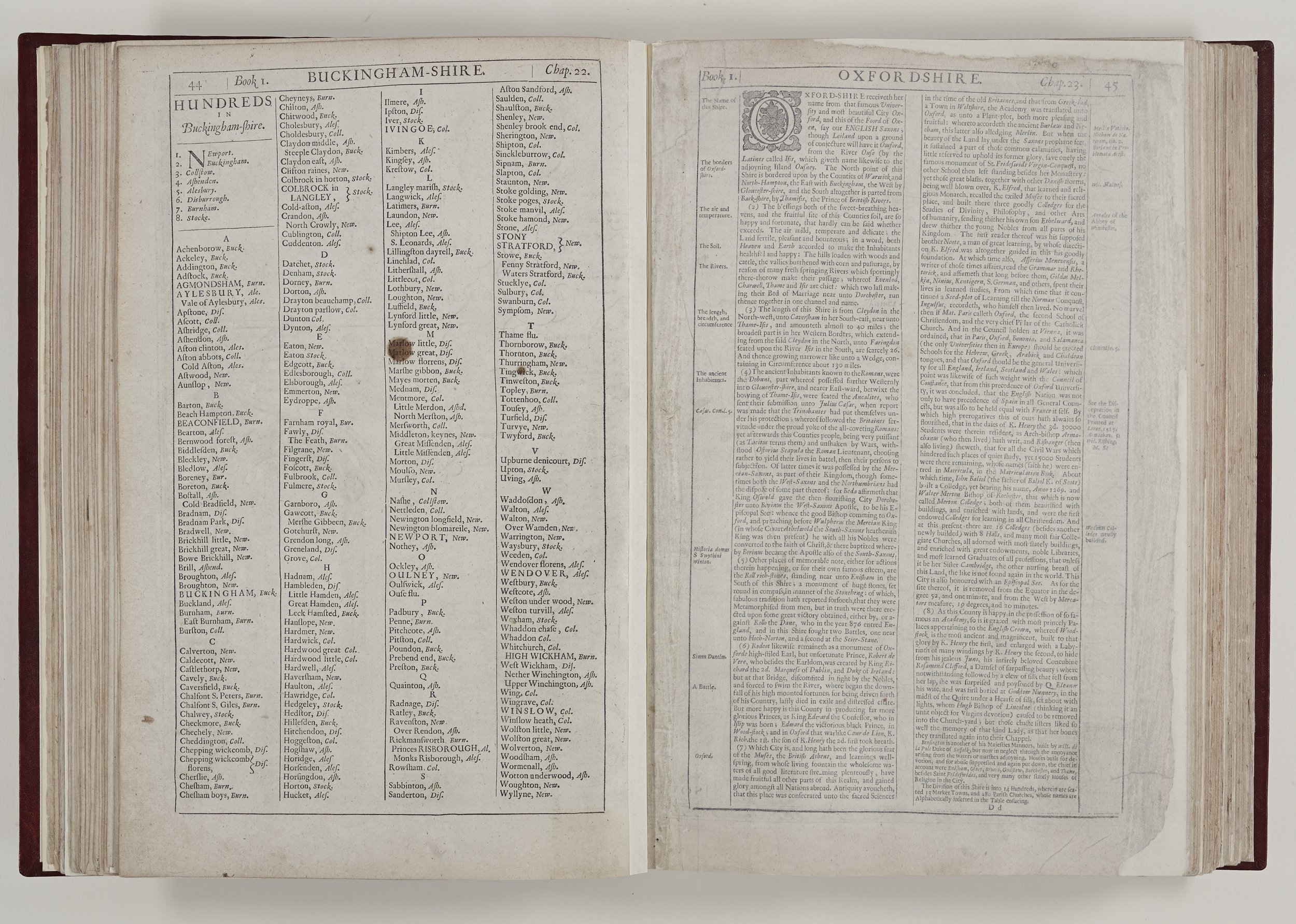

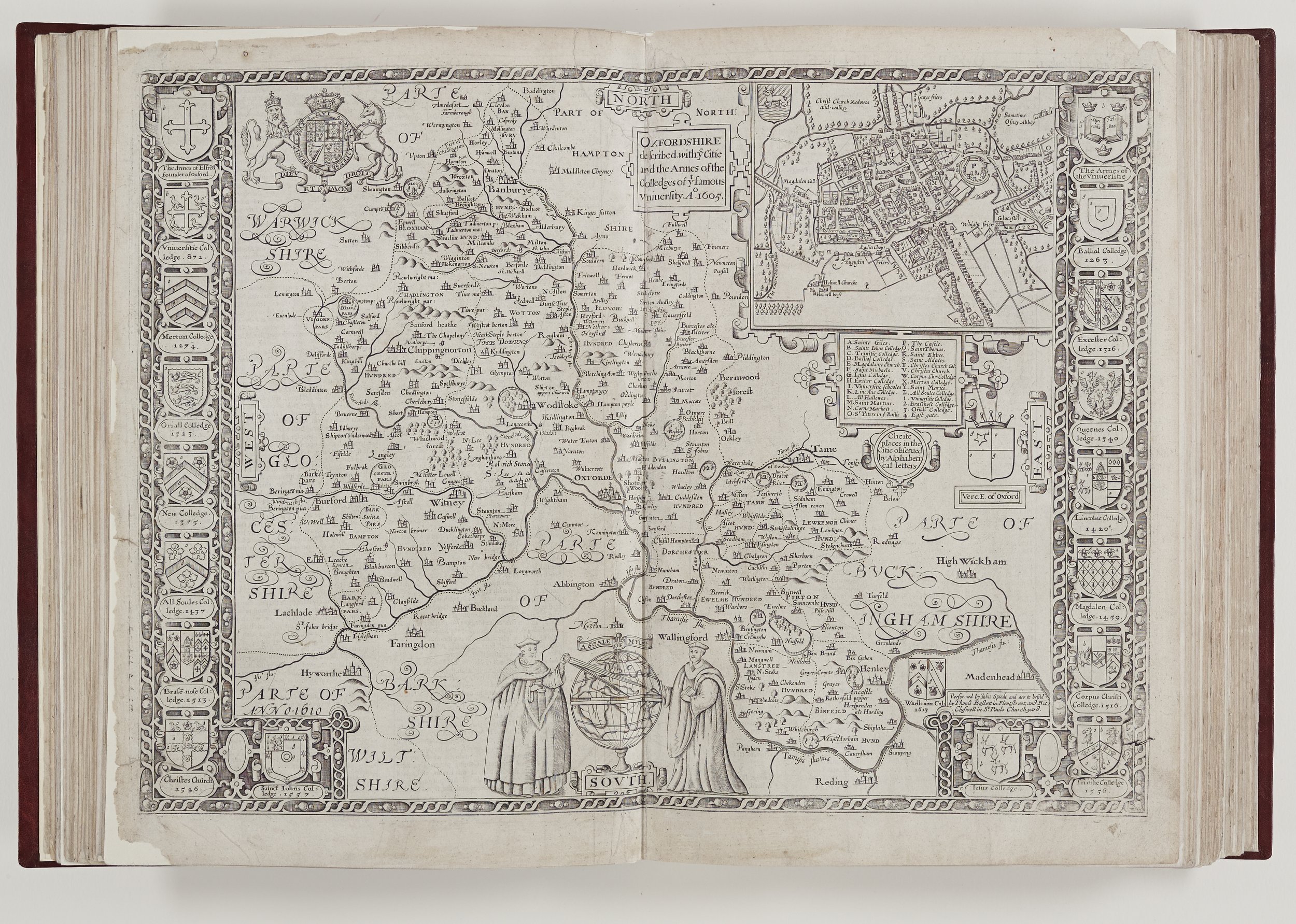

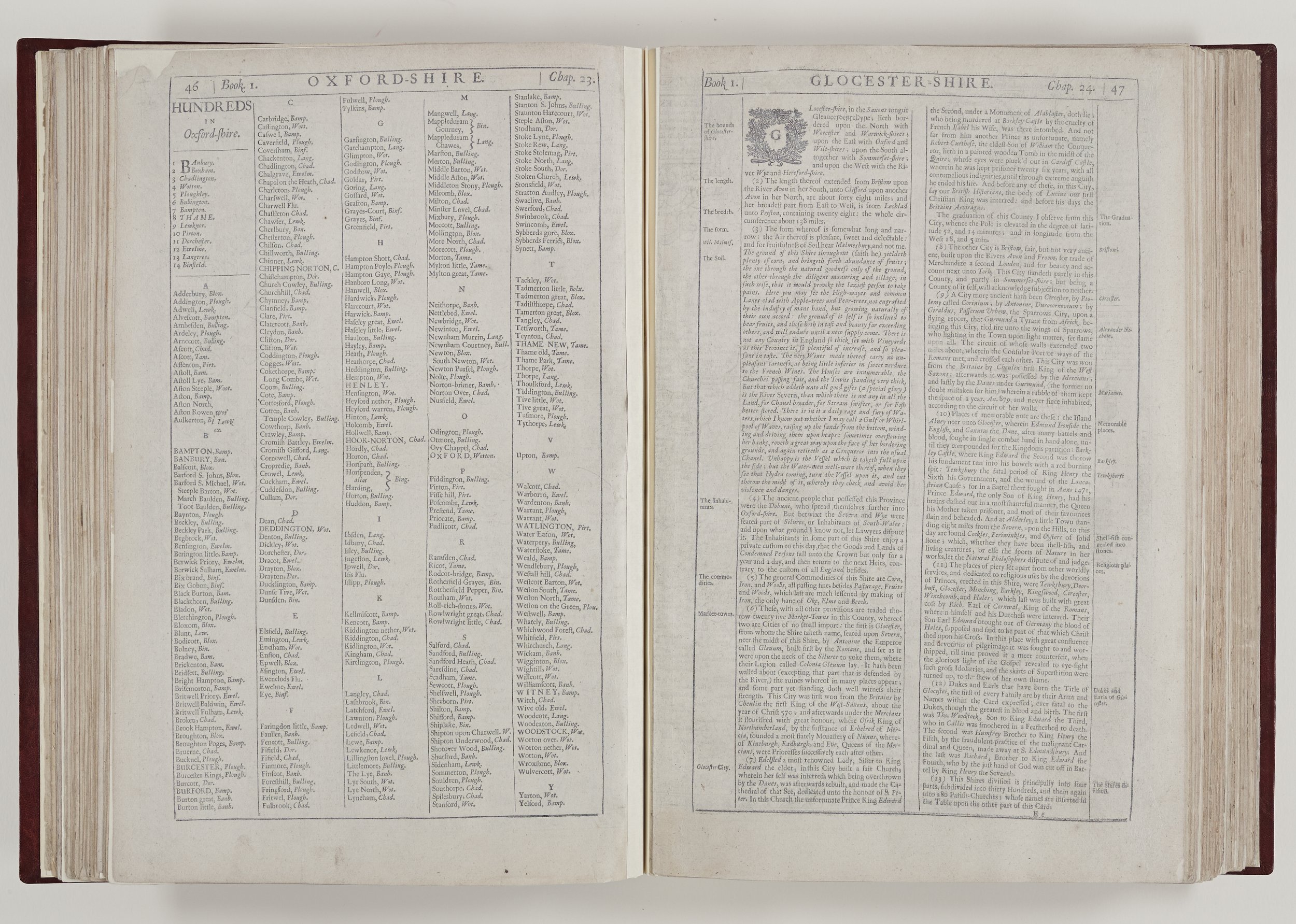

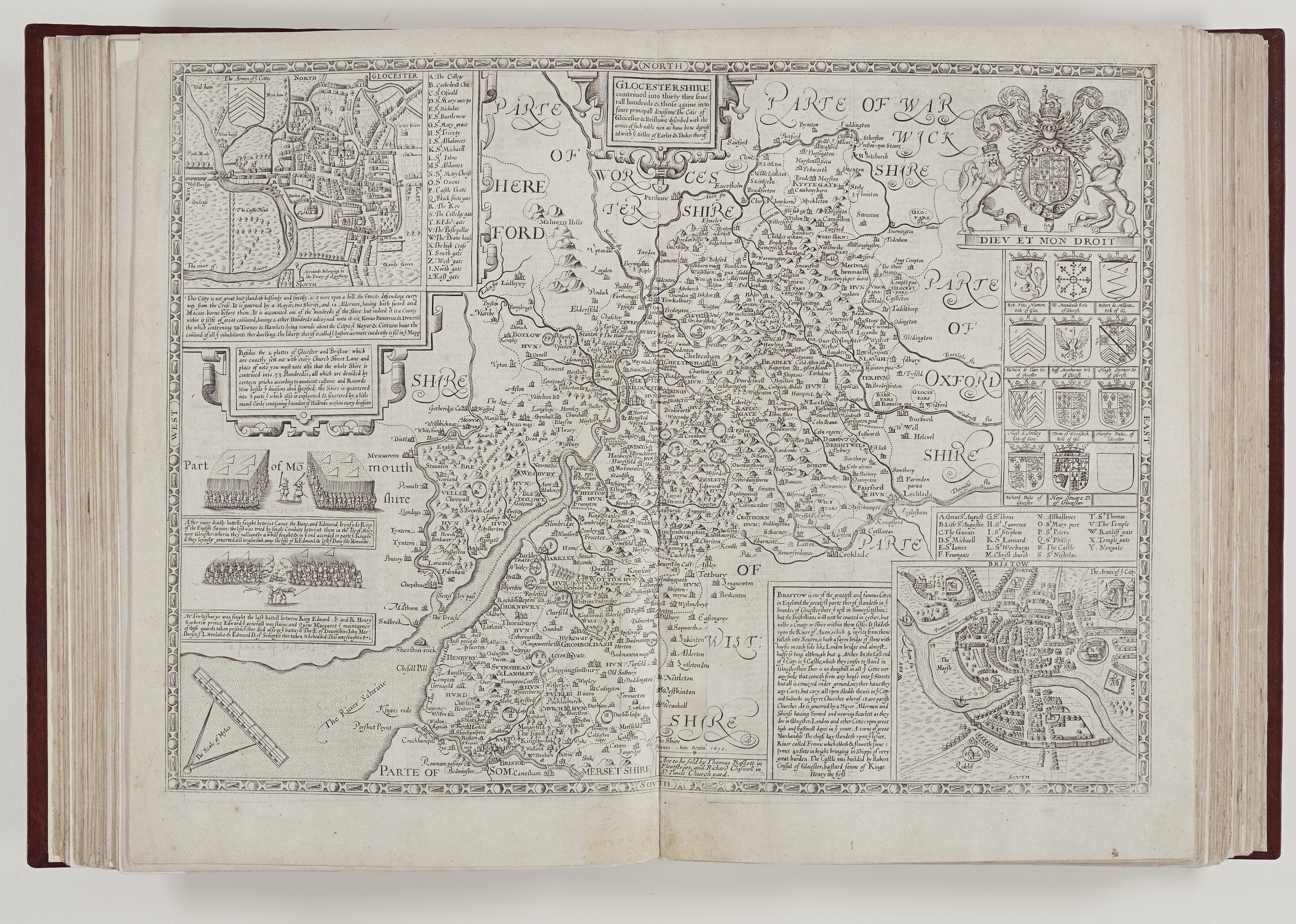

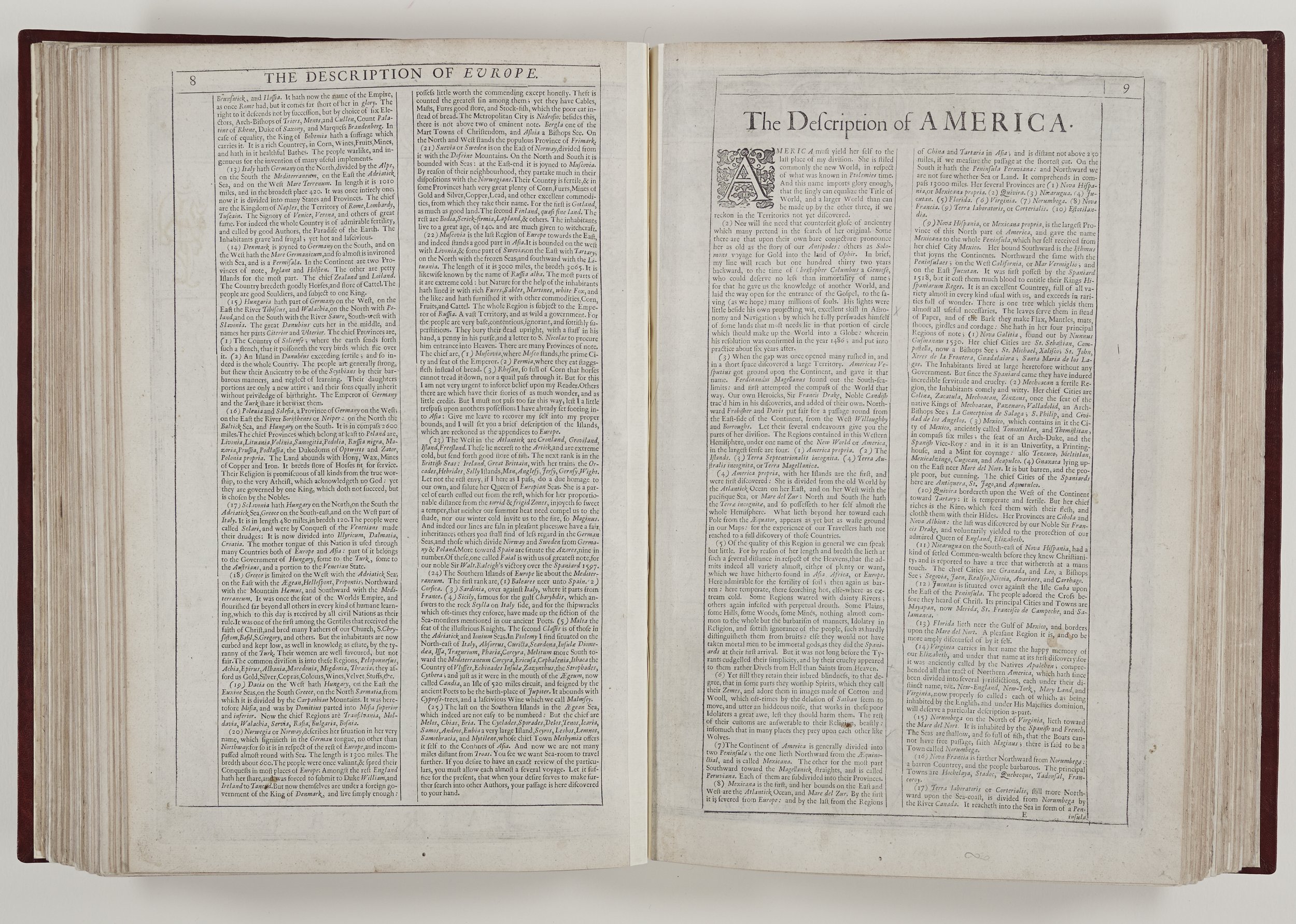

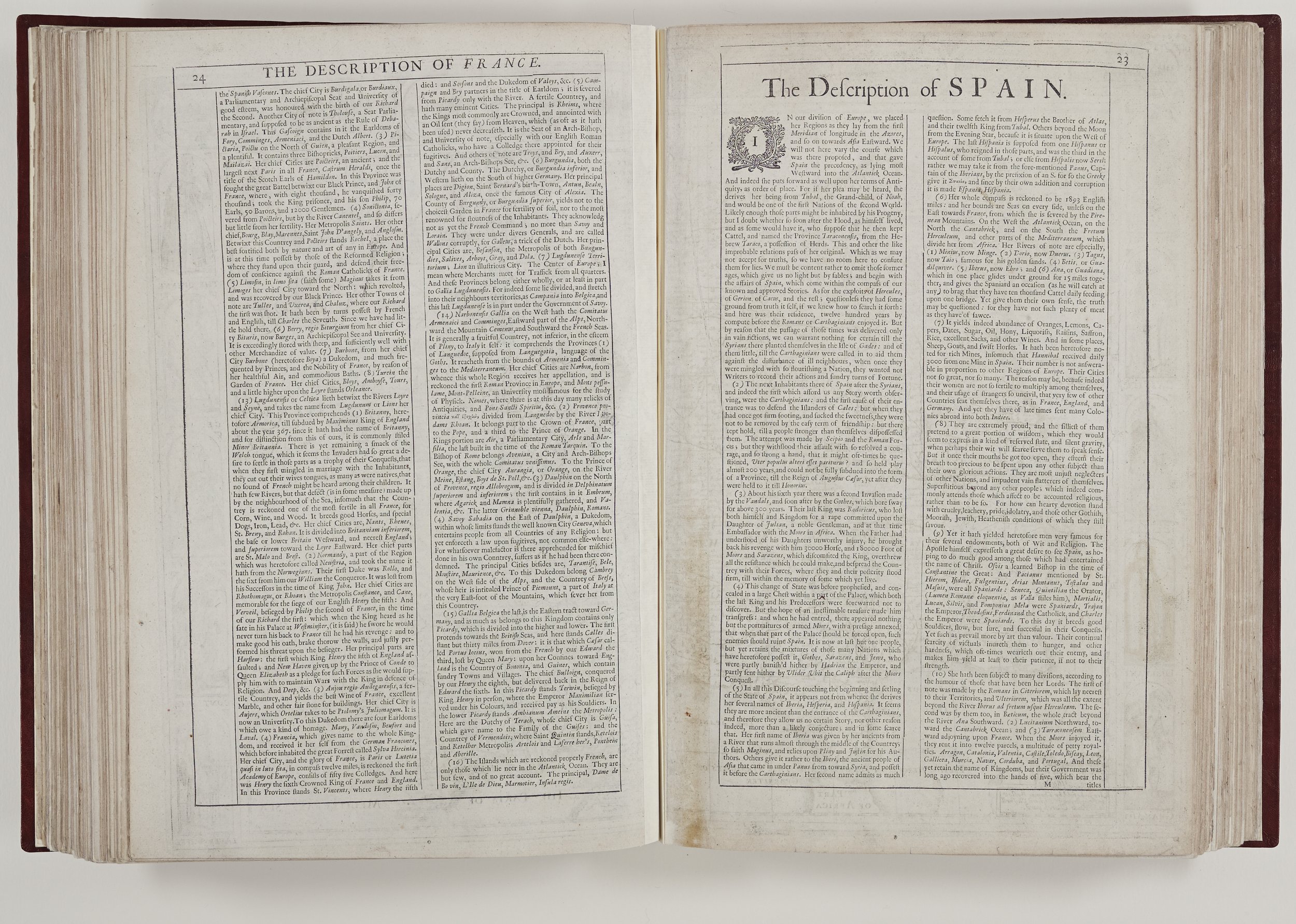

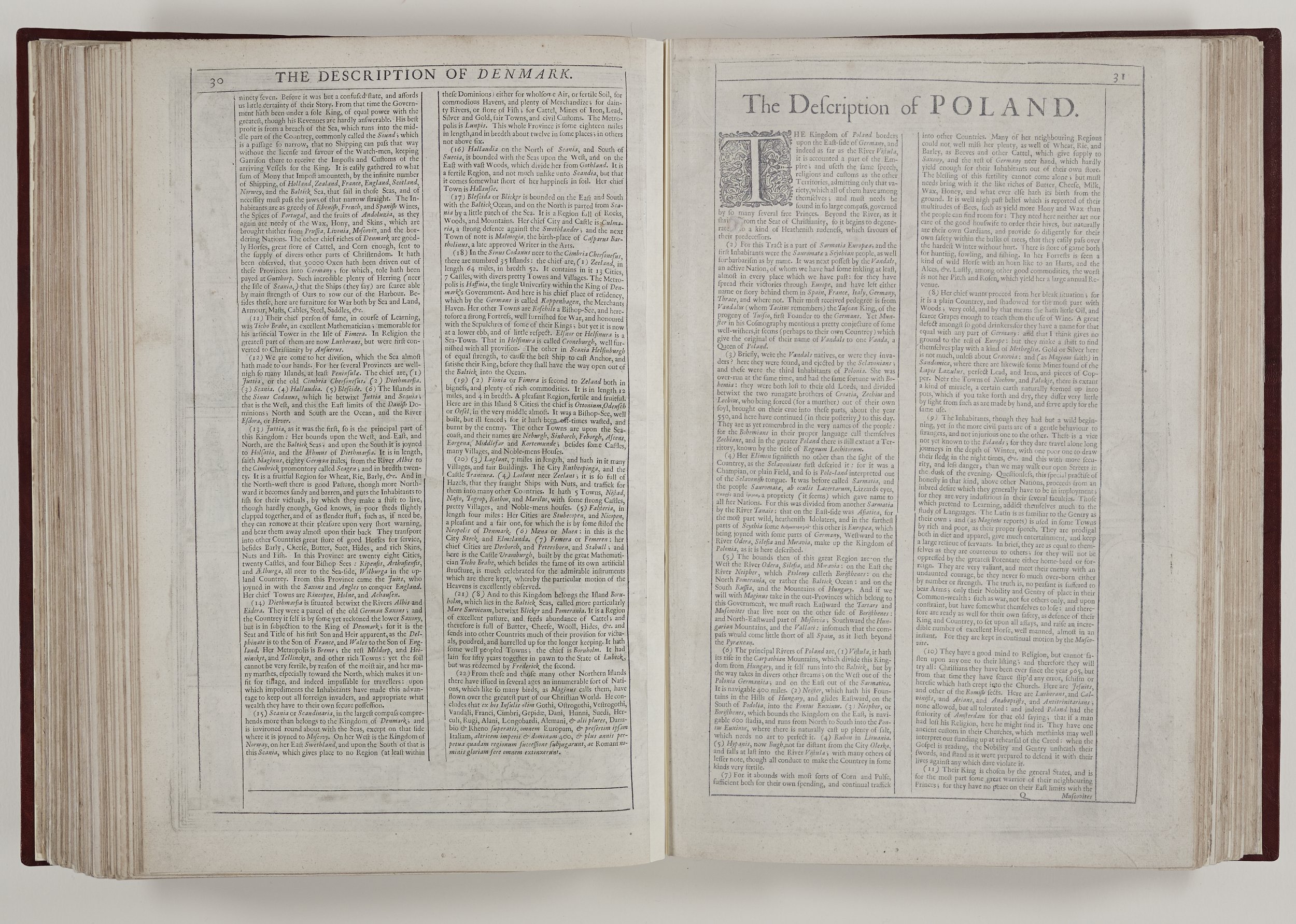

Visitors are always drawn to the Cathedral’s 1676 Speed Atlas when it is on display. They enjoy seeing their native county or country and frequently marvel at the skill of cartographers who did not have the knowledge and technology of later centuries at their fingertips. They are often surprised by the accuracy of some maps and interested in the archaic spellings of place names. Unfortunately, very few have the time or the necessary good eyesight to read the detailed text which accompanies most maps but it is here that we can catch John Speed talking directly to the reader and his voice is clear and very entertaining!

John Speed was born in Farndon, Cheshire about 1552. The son of a tailor, he originally pursued this occupation but by the 1580s had developed a fascination with history and had associated with printers, engravers and antiquarians. Perhaps his first foray into historical work was as co-complier of biblical genealogies. He later received a licence to insert these biblical family trees into every copy of the authorised version of the Bible and the Chapter Library contains Bibles from 1613 and 1625 which include his lengthy genealogies.

Engraving of John Speed by Thomas Savery 1632.

By the 1590s Speed had developed an interest in cartography, publishing a map of biblical Canaan and presenting maps to Queen Elizabeth I. In 1598 Speed was able to focus entirely on his historical interests, having been granted a sinecure and room in the Customs House by Queen Elizabeth I, under the patronage of Sir Fulke Greville. (1554-1628) Speed always acknowledged the help of others in producing his work and in his Theatre description of Warwick Castle, where Greville was then resident, he gives his patron fulsome praise. He thankfully concedes that Greville was responsible for “setting this hand free from the daily employments of a manual trade and giving it full liberty to express the inclination of my mind.”

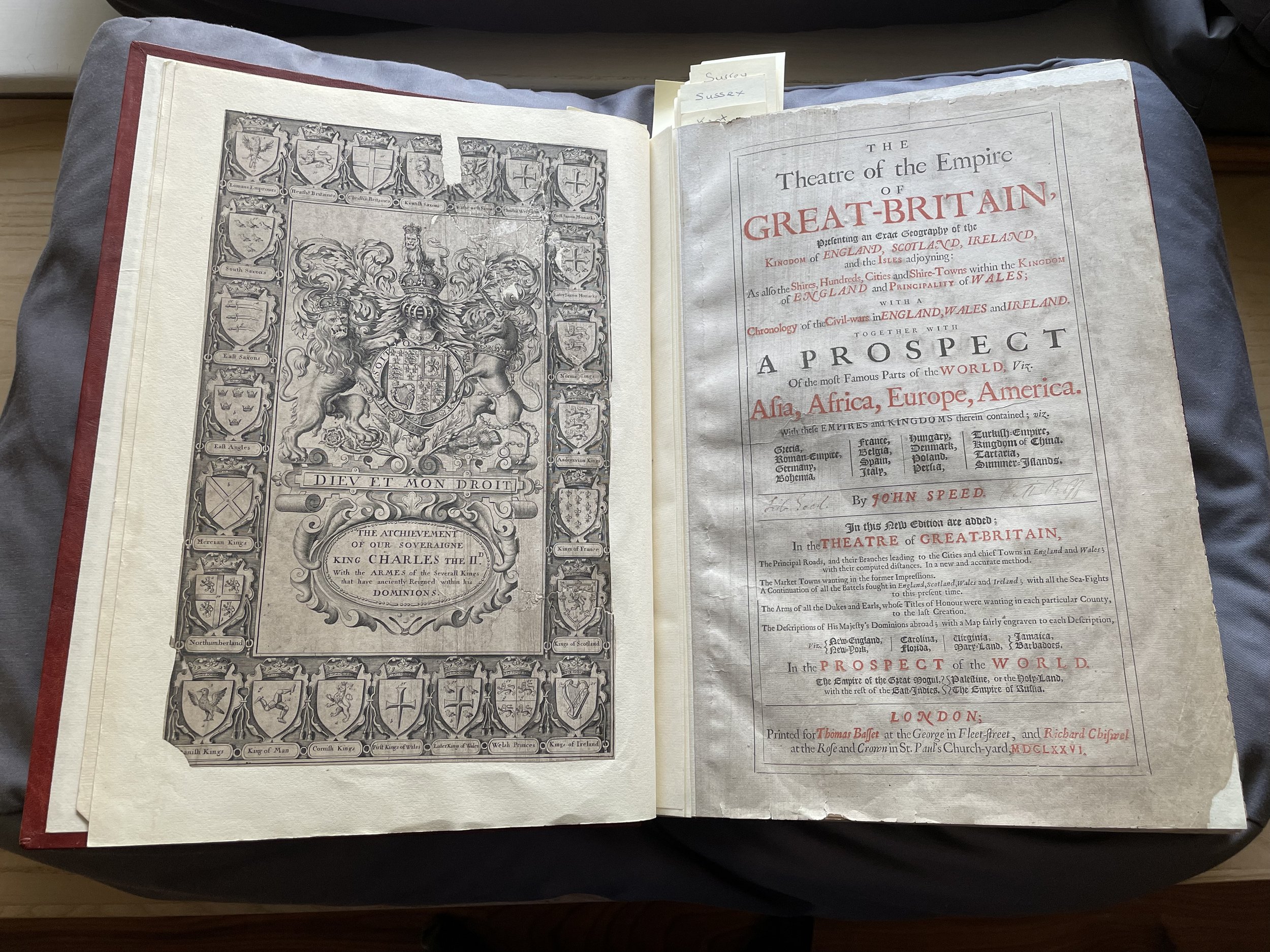

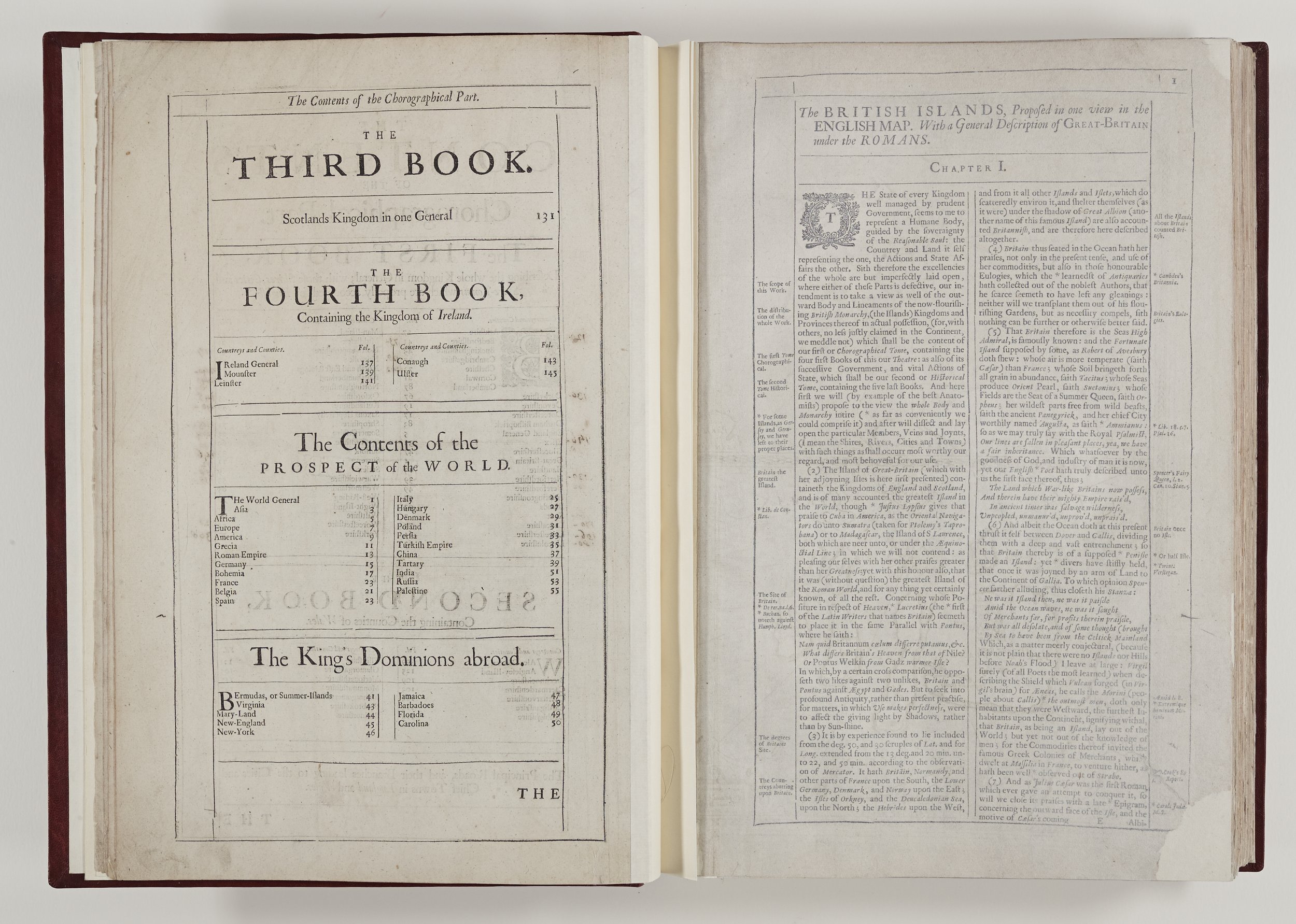

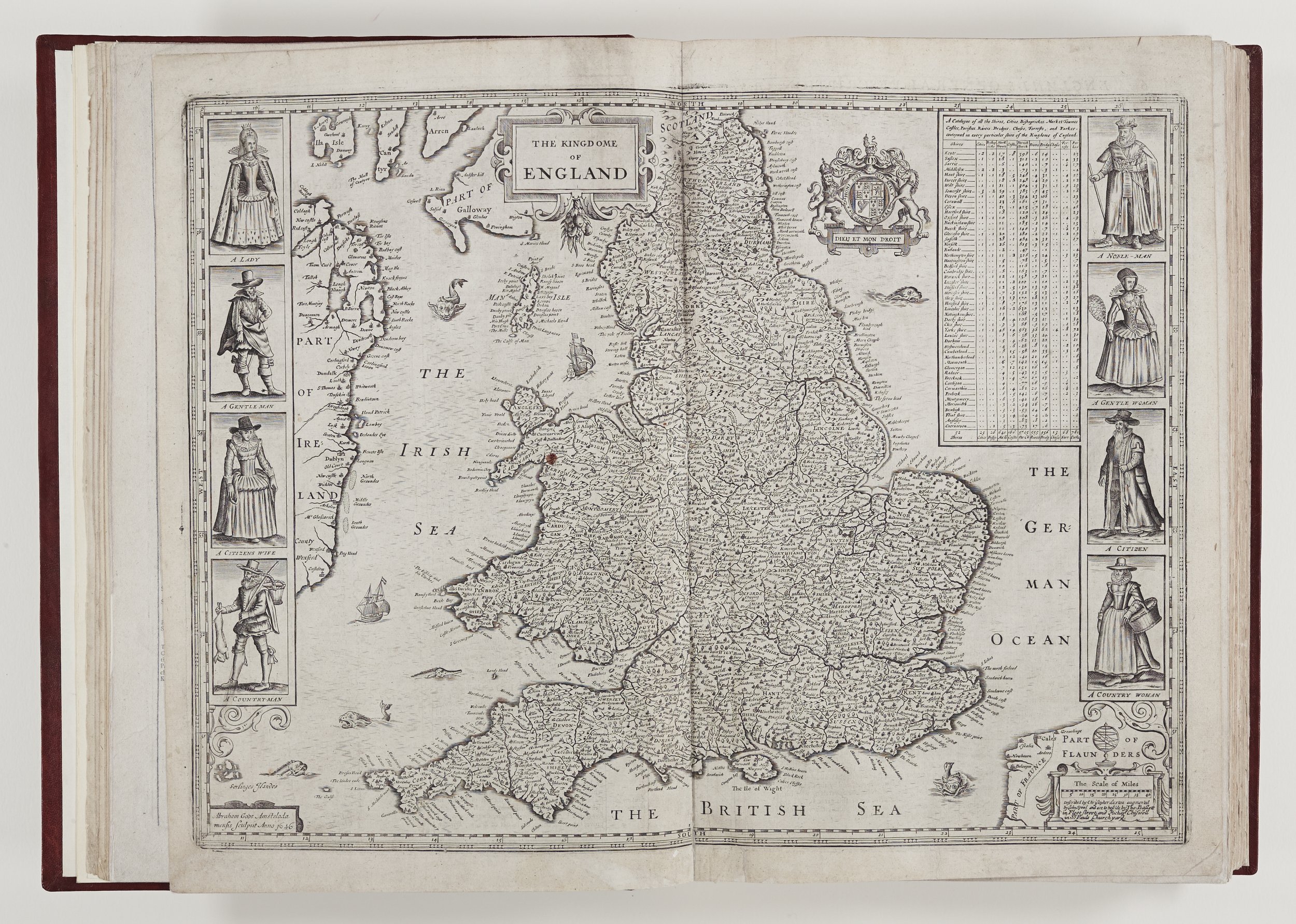

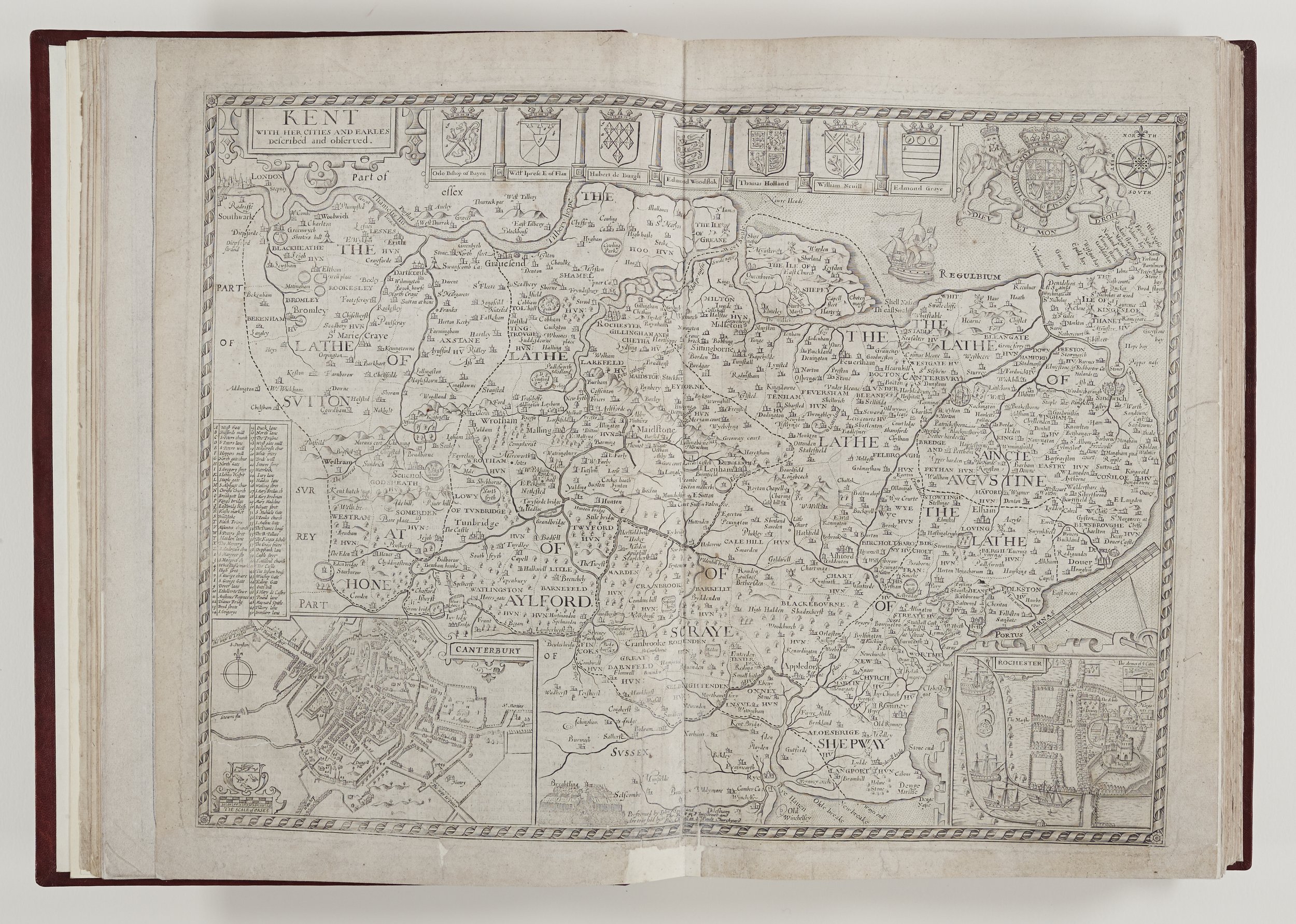

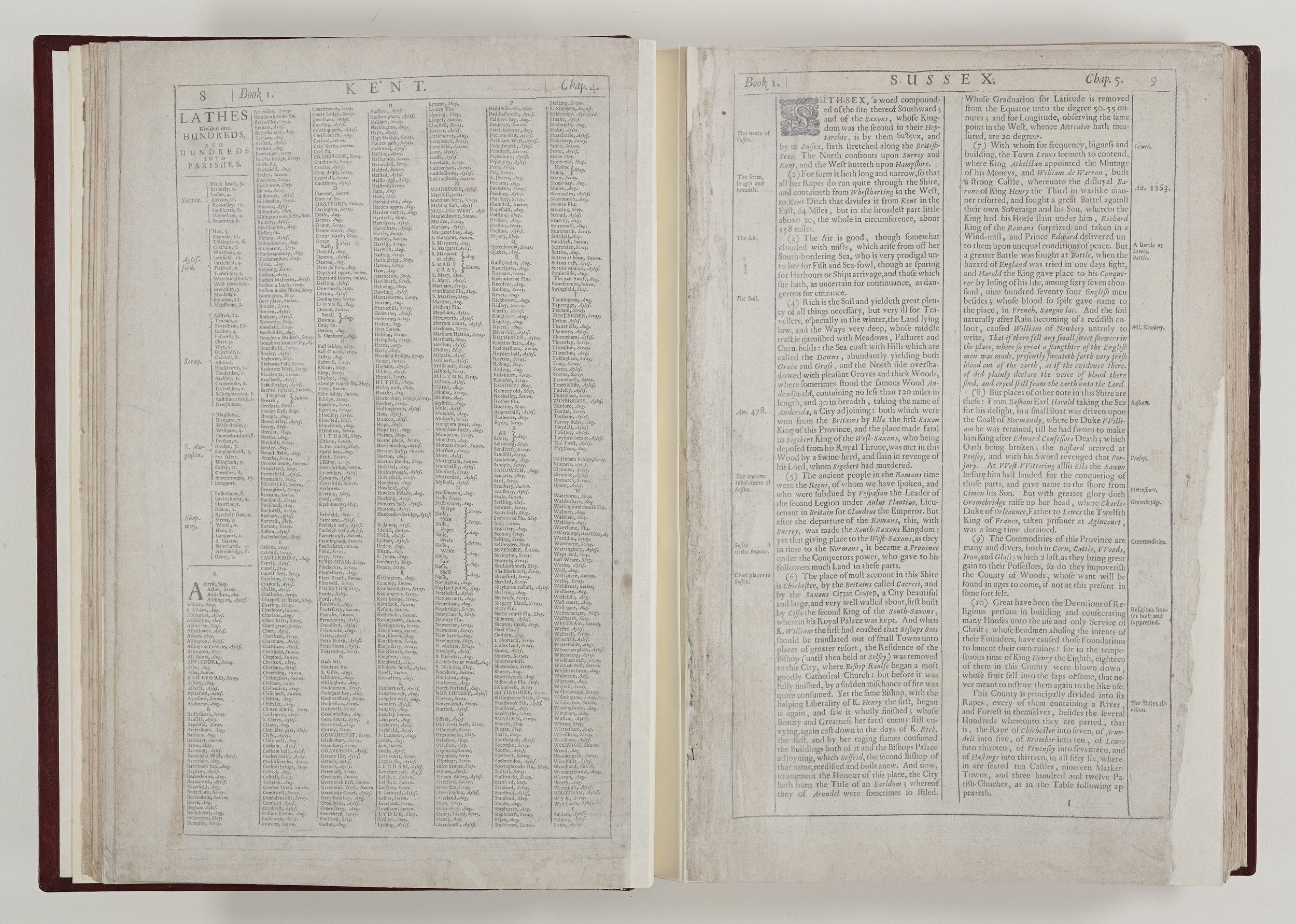

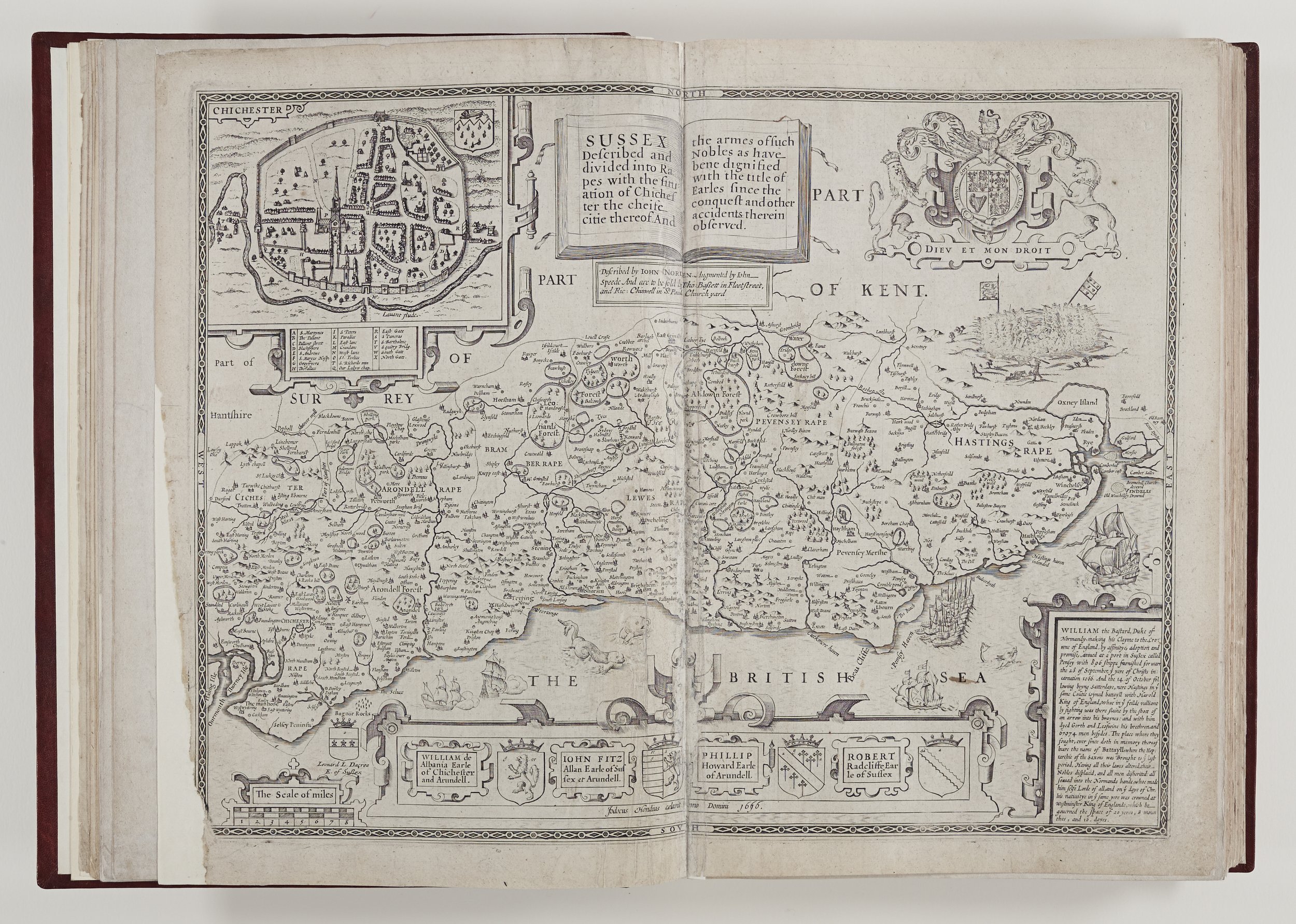

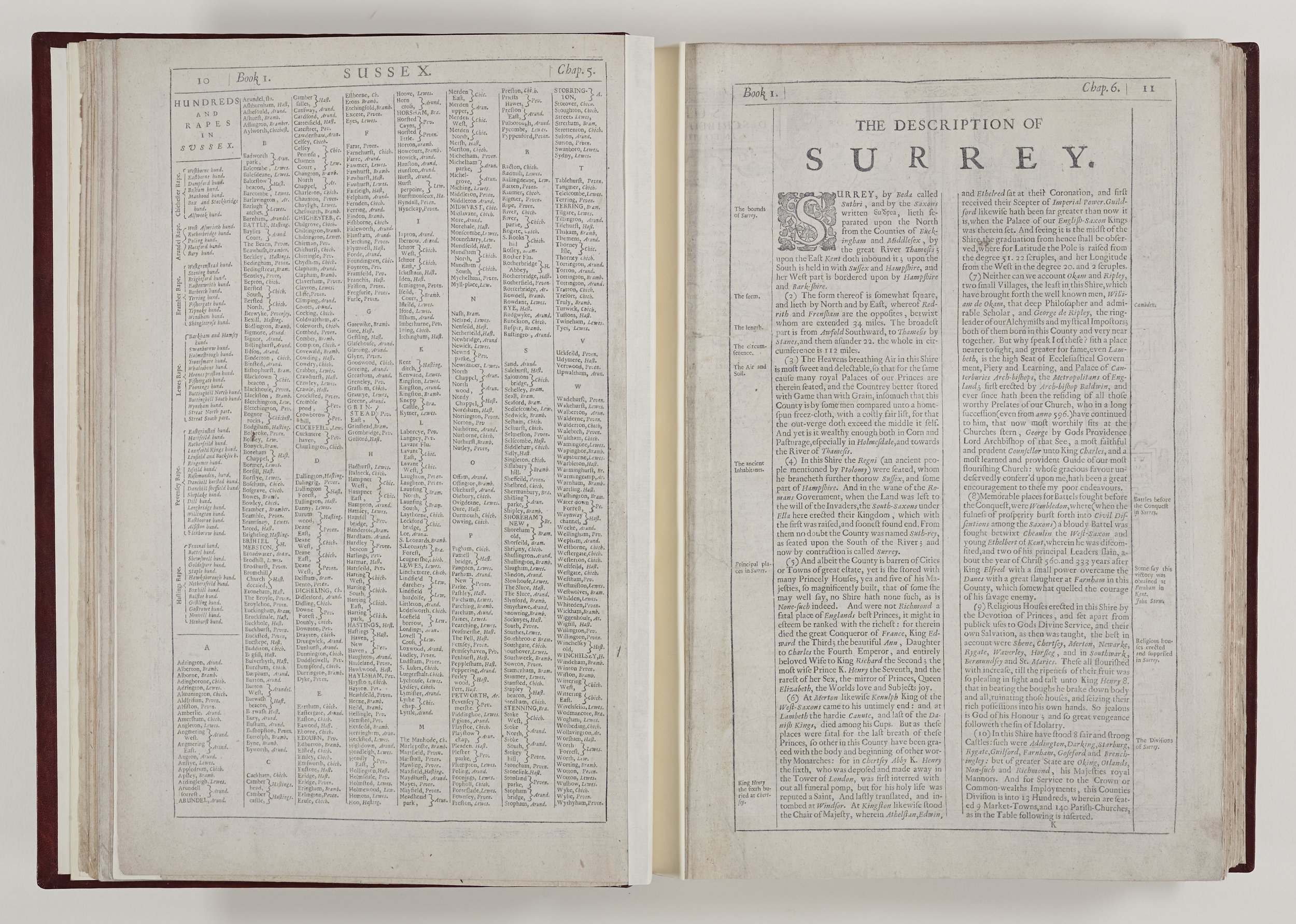

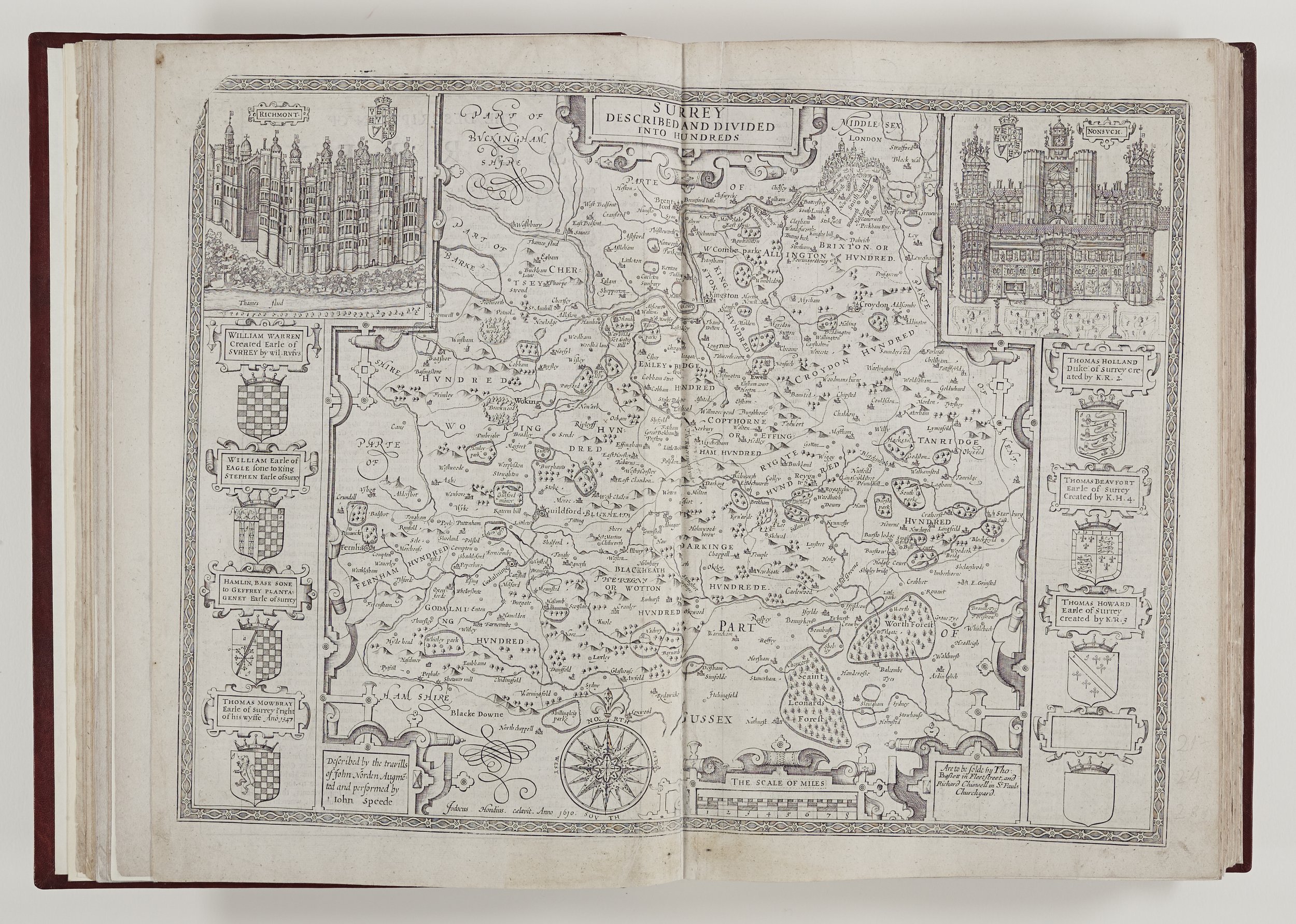

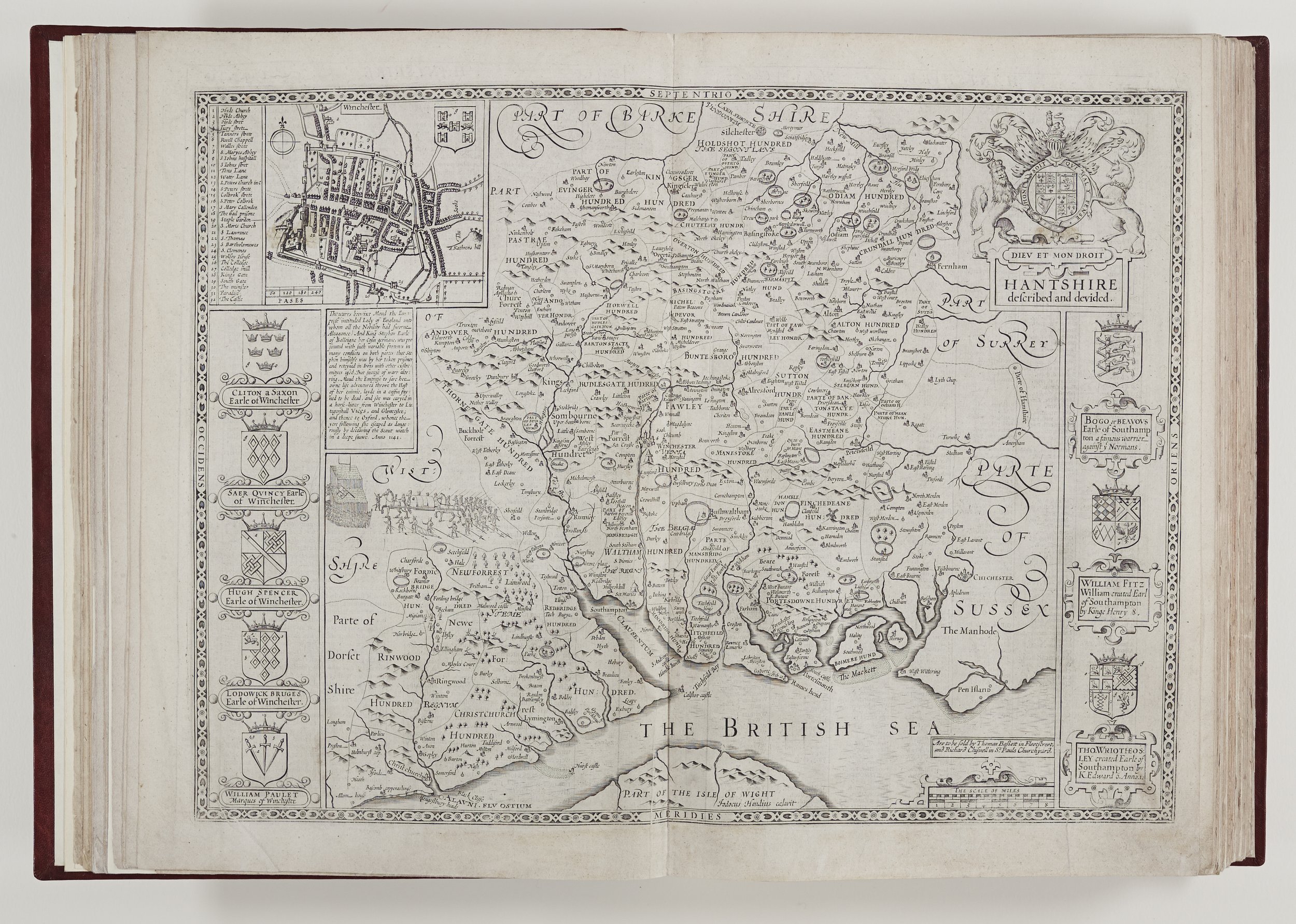

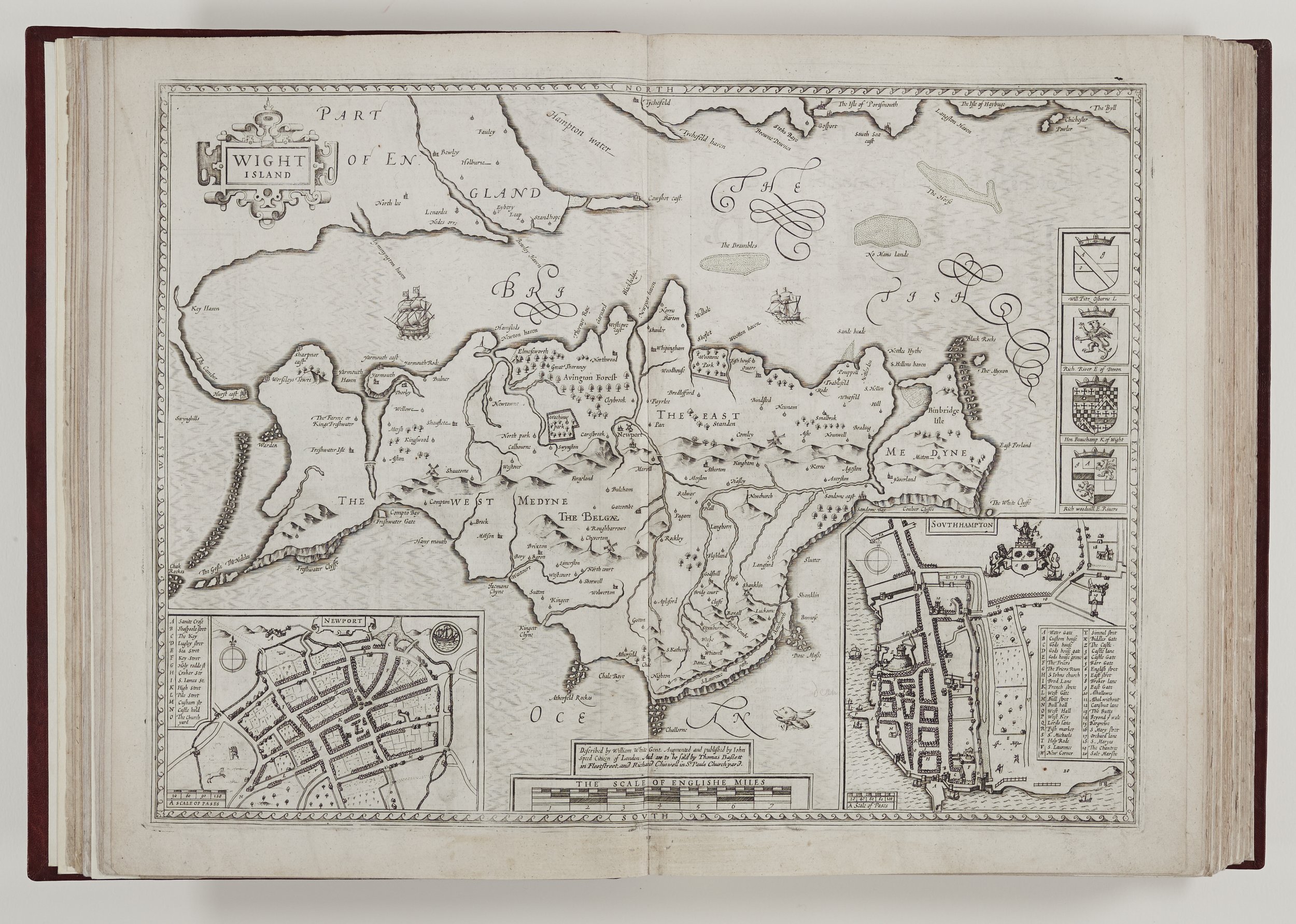

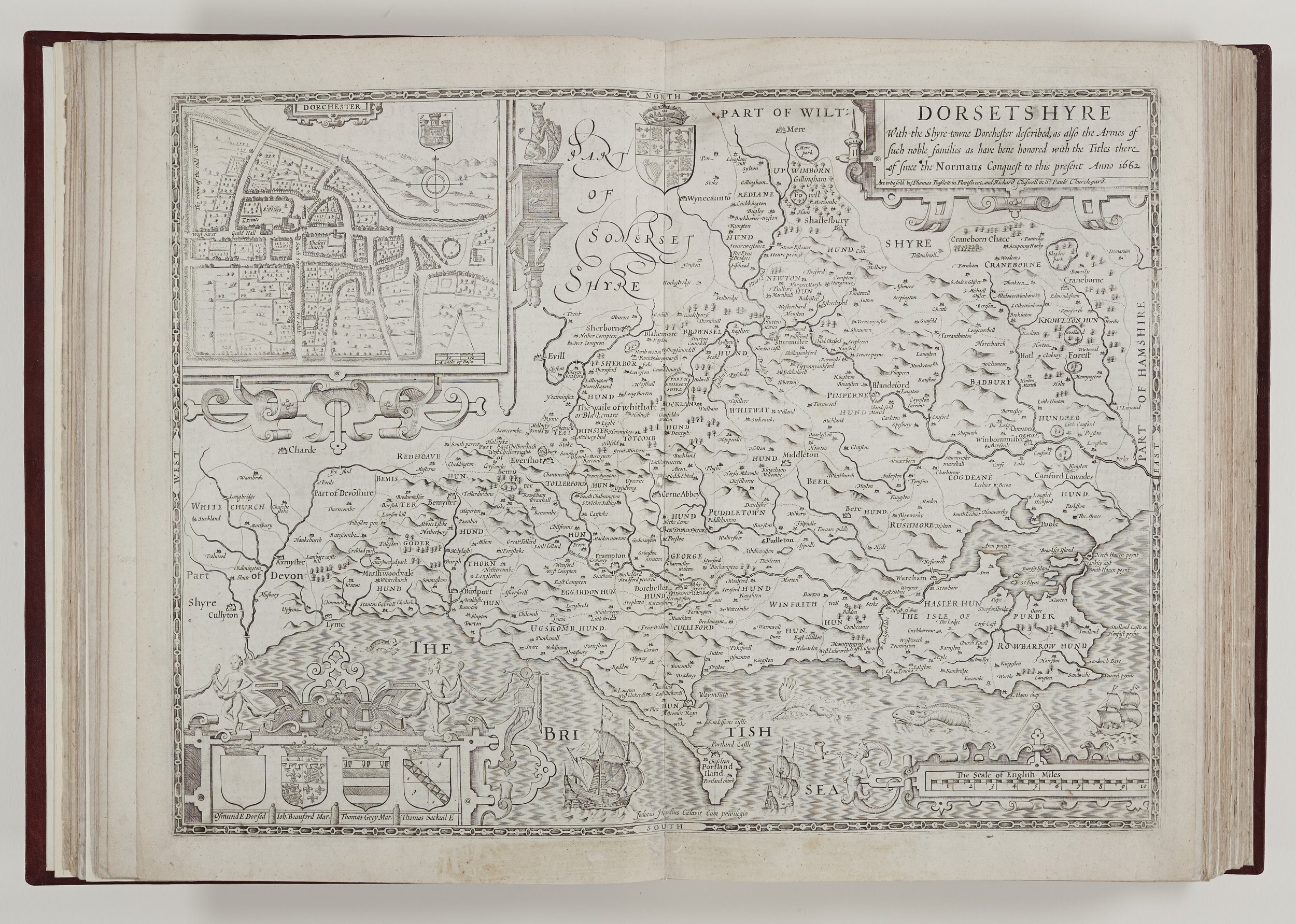

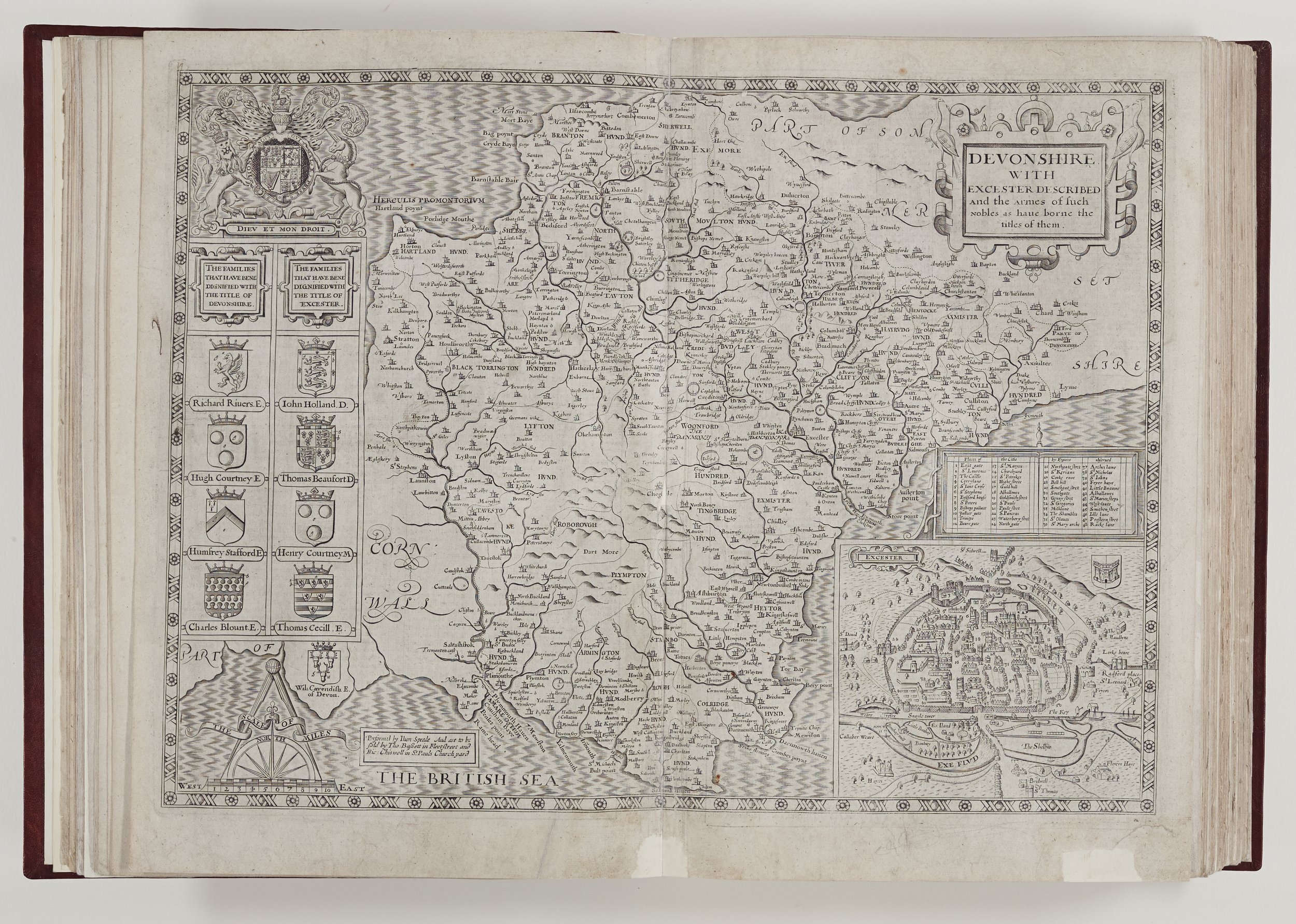

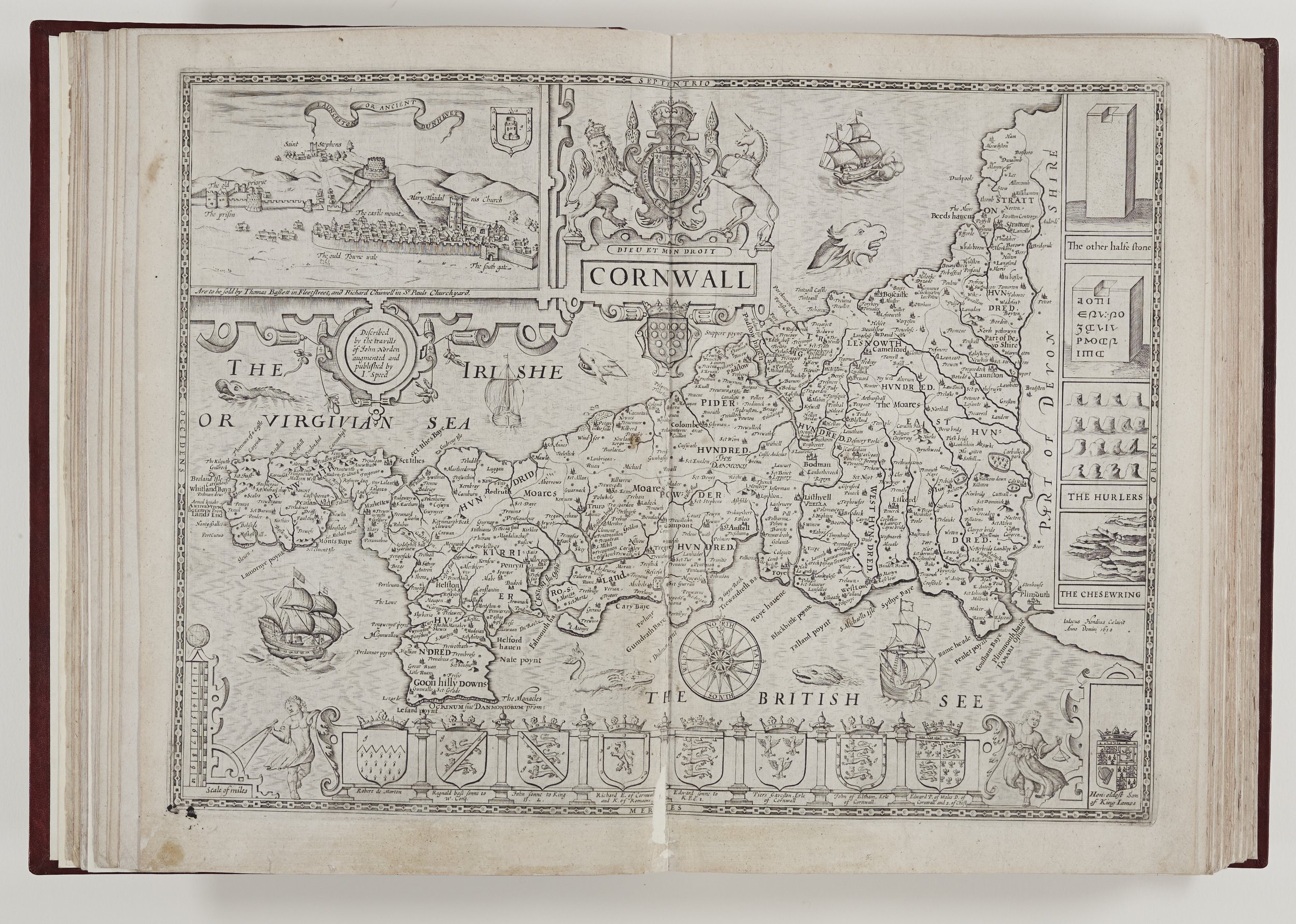

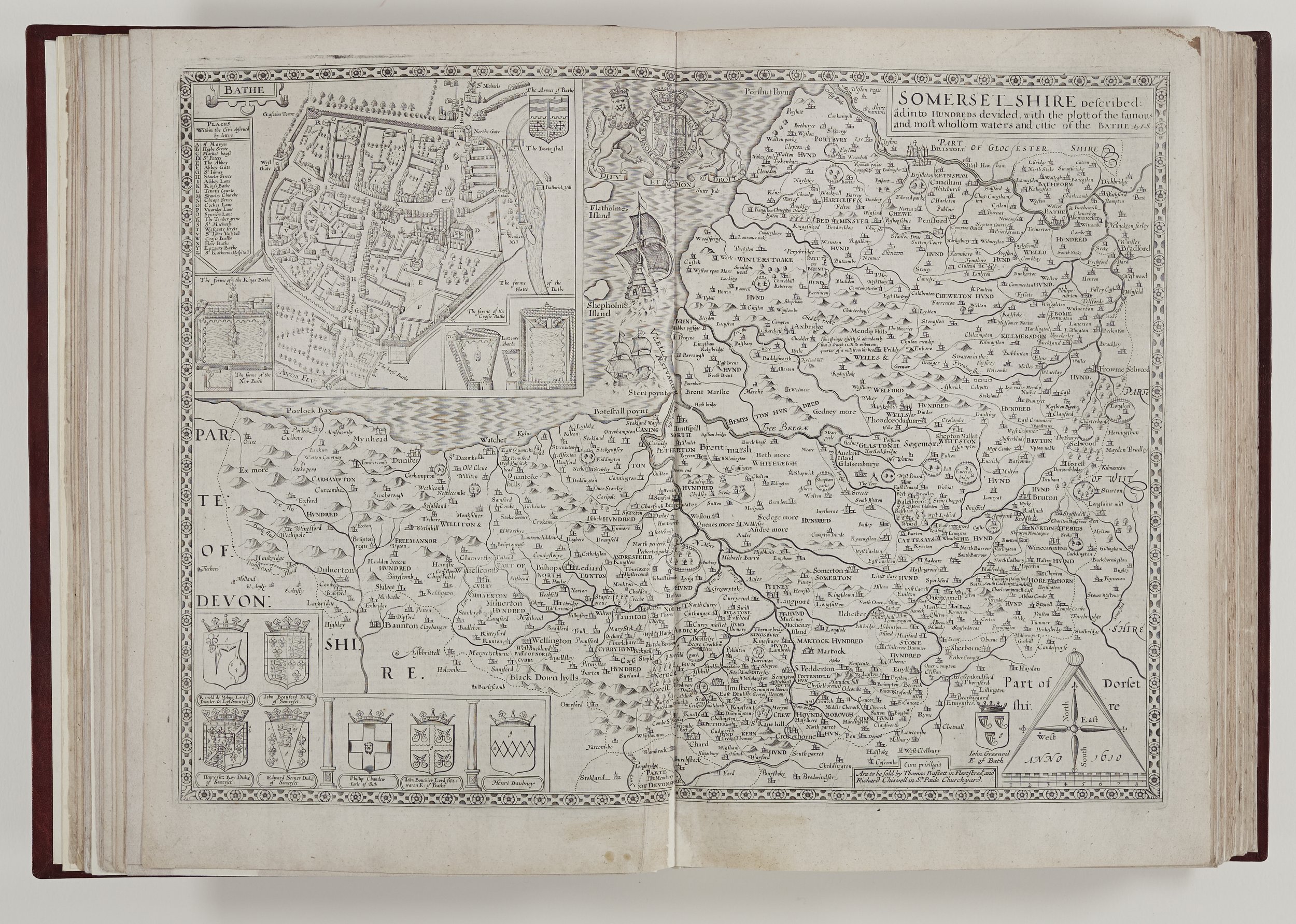

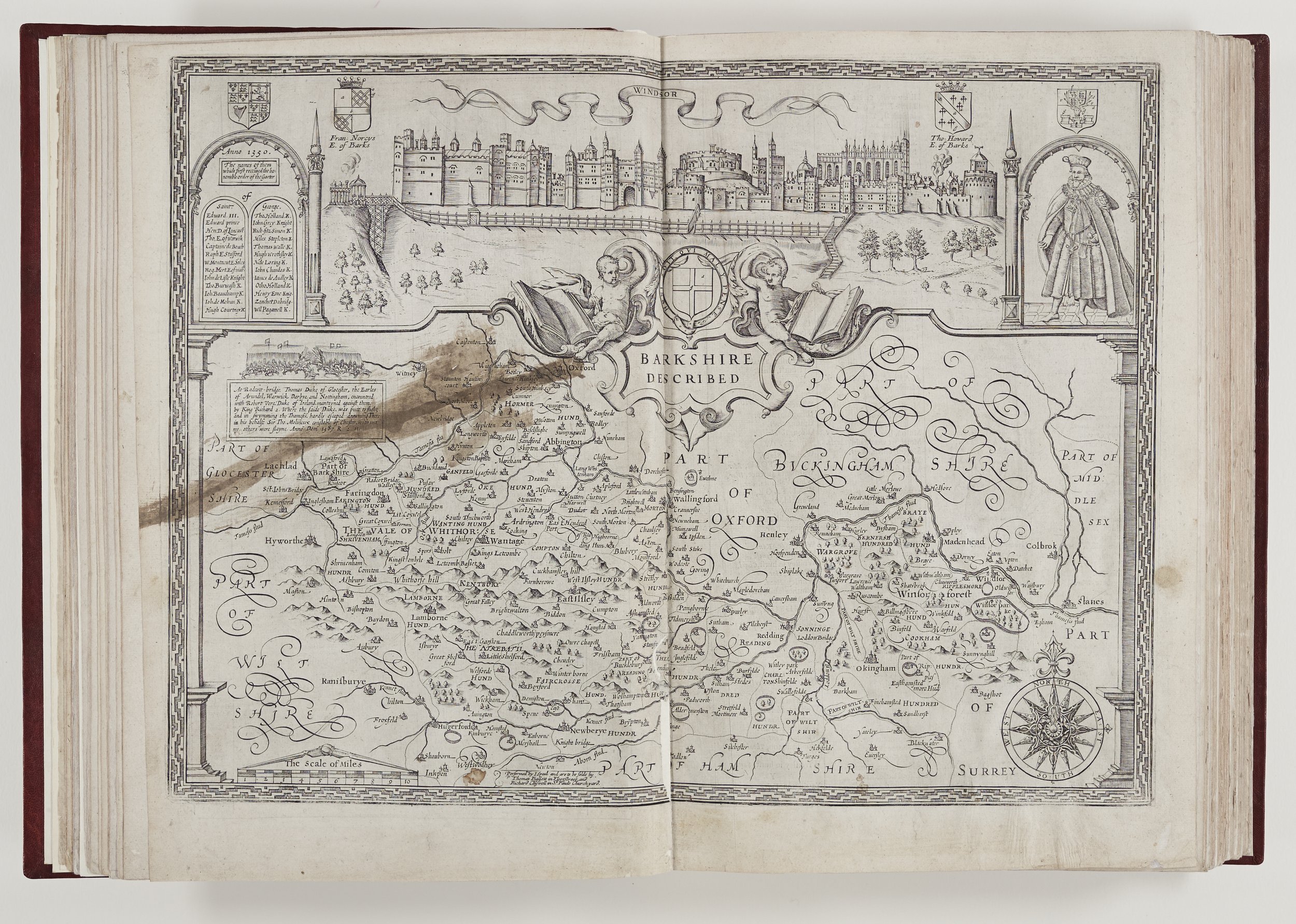

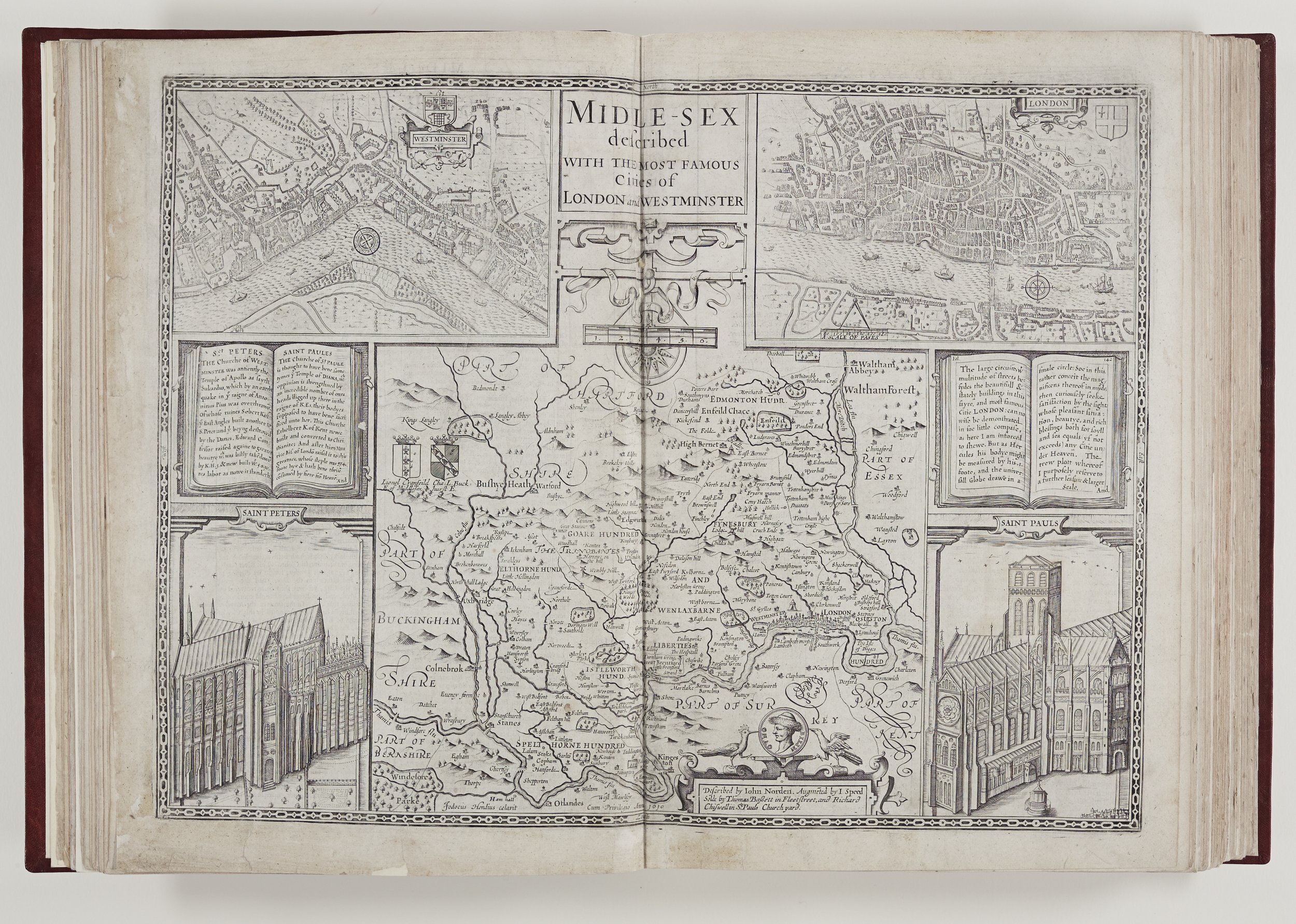

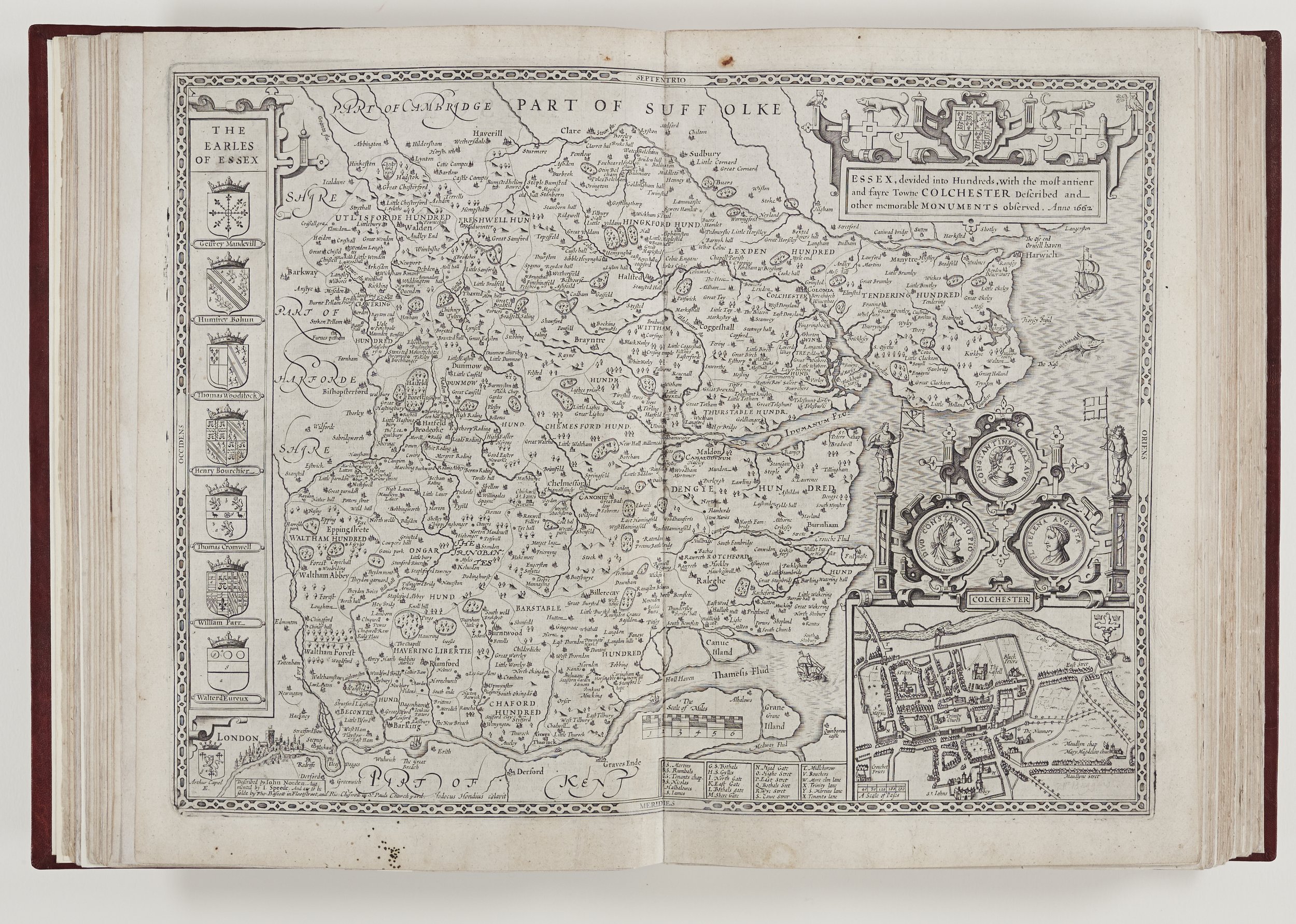

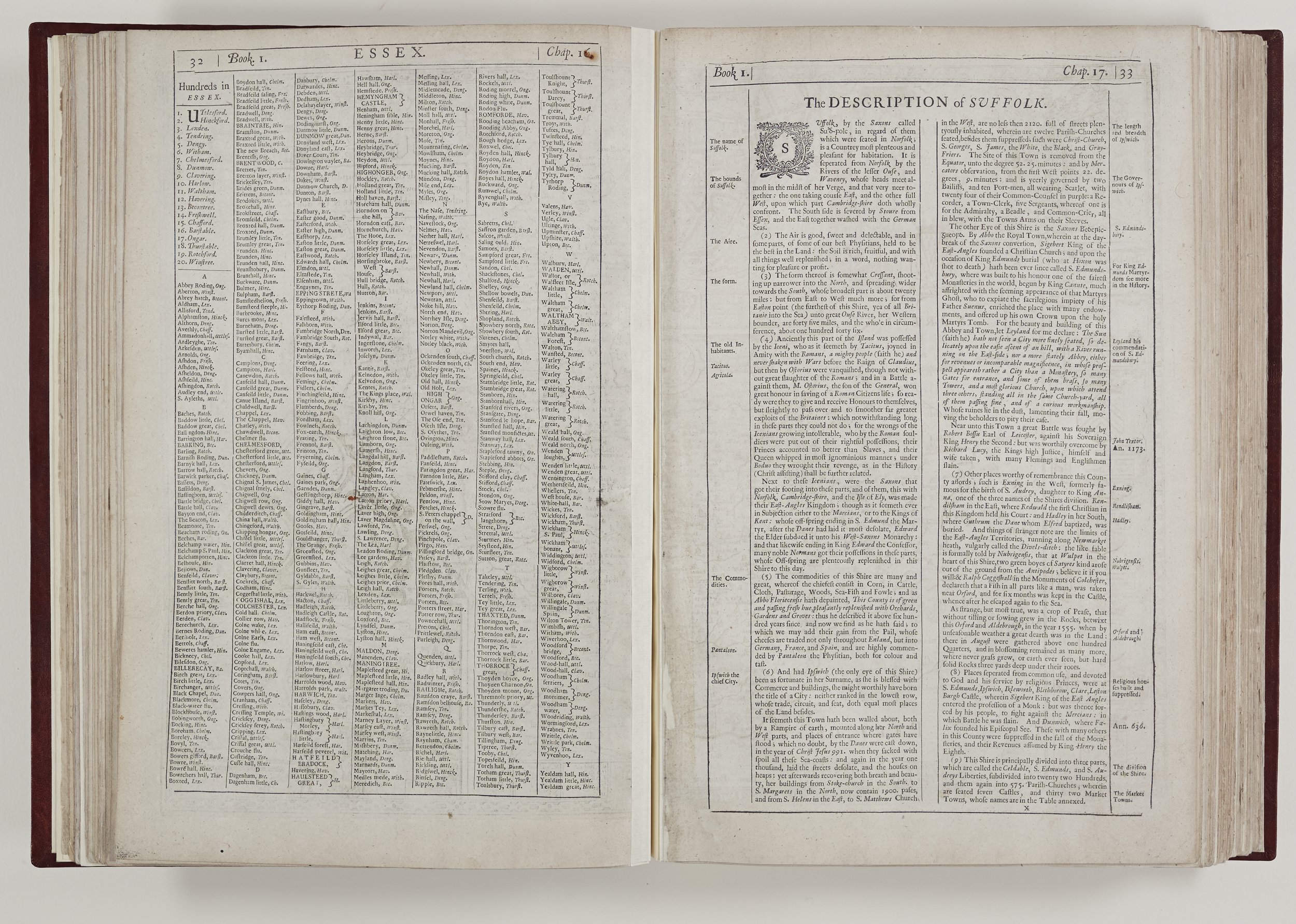

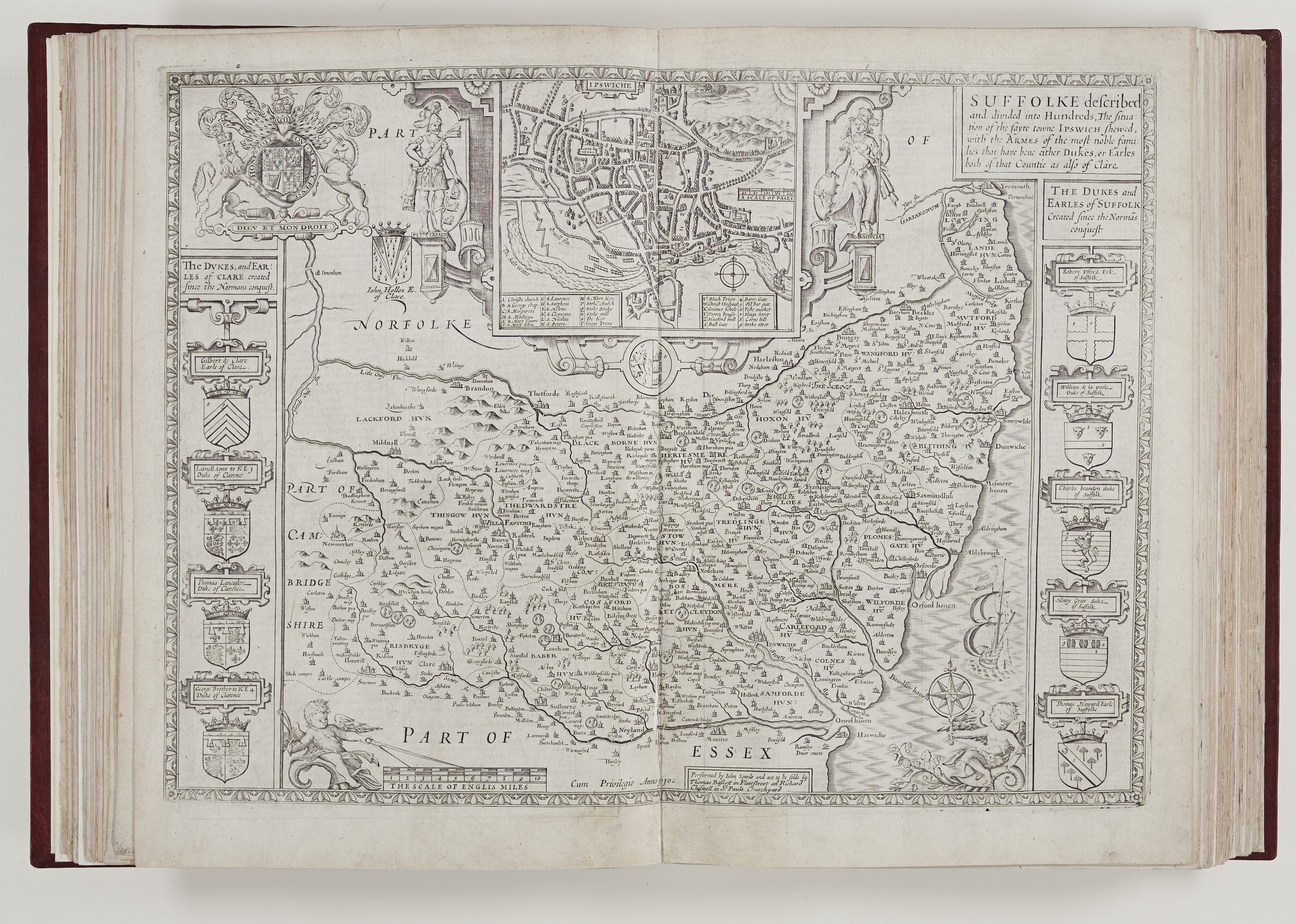

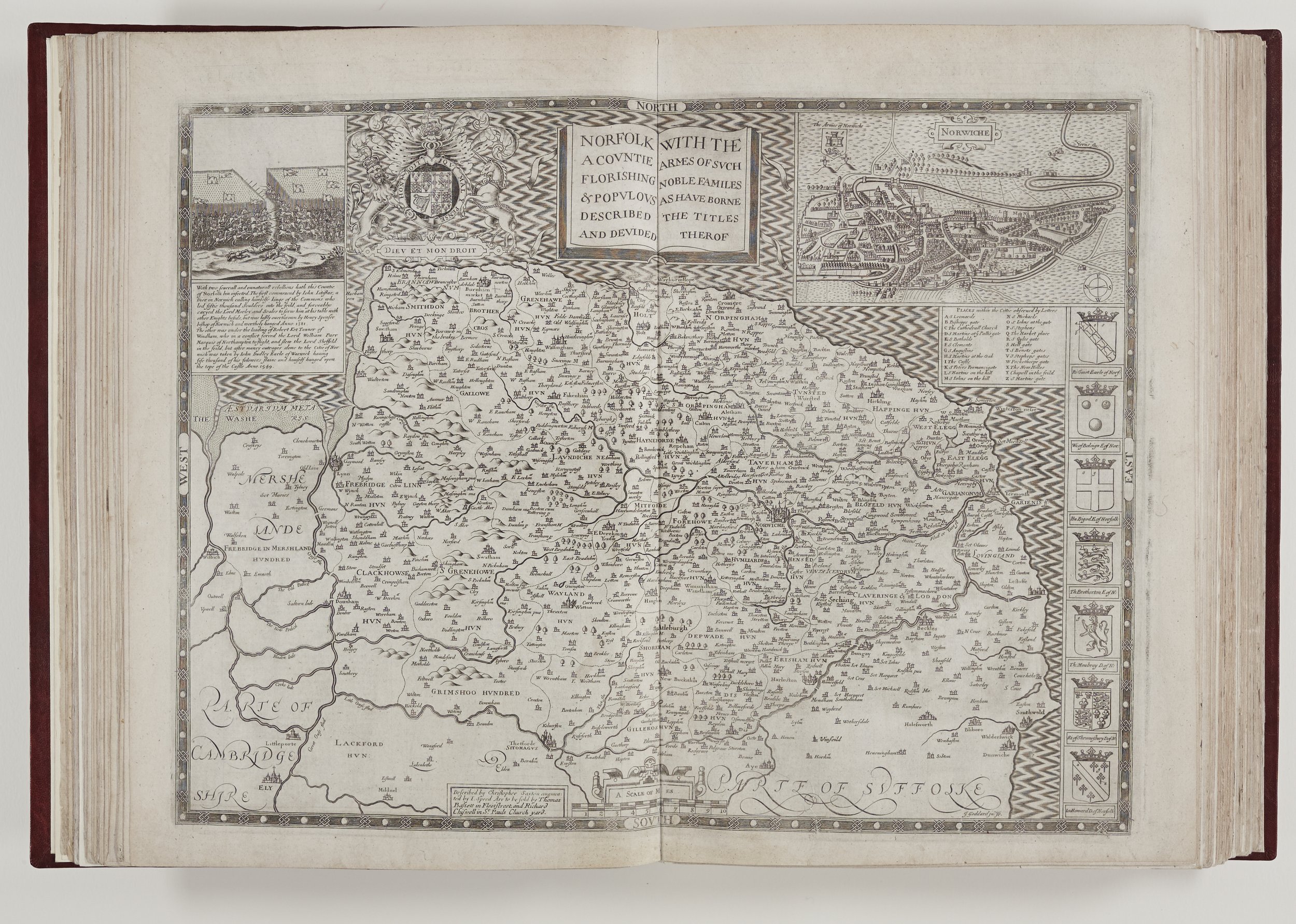

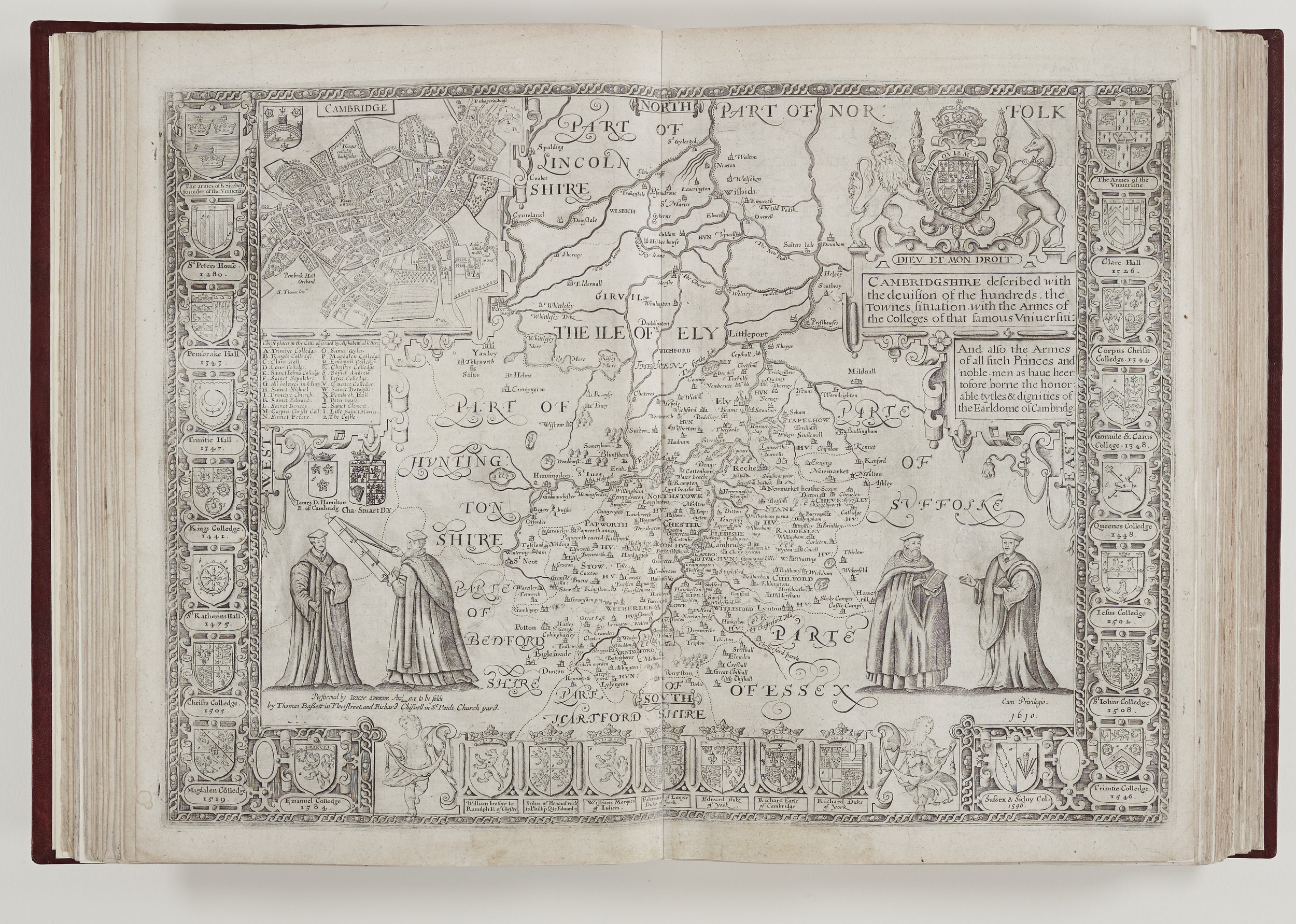

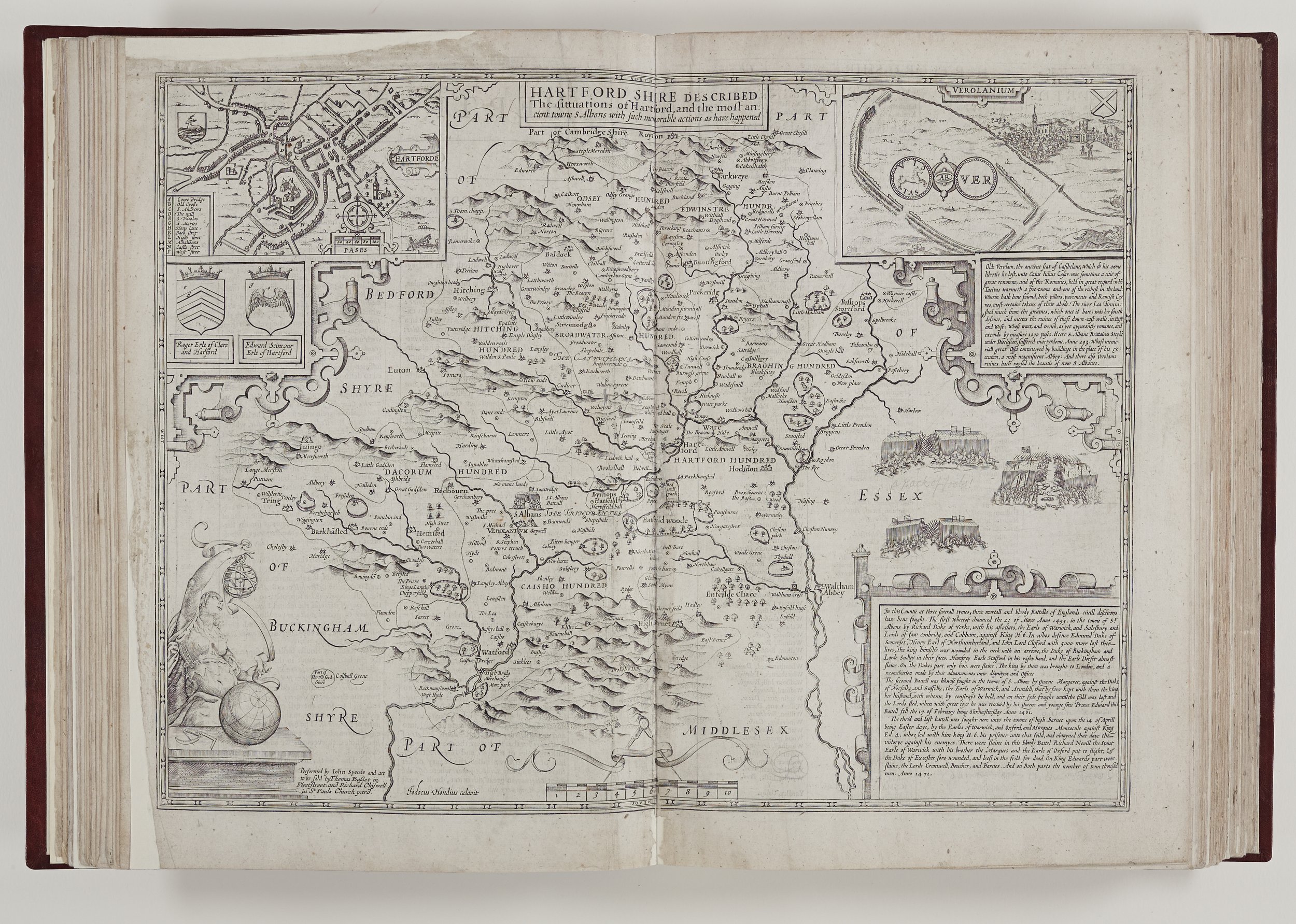

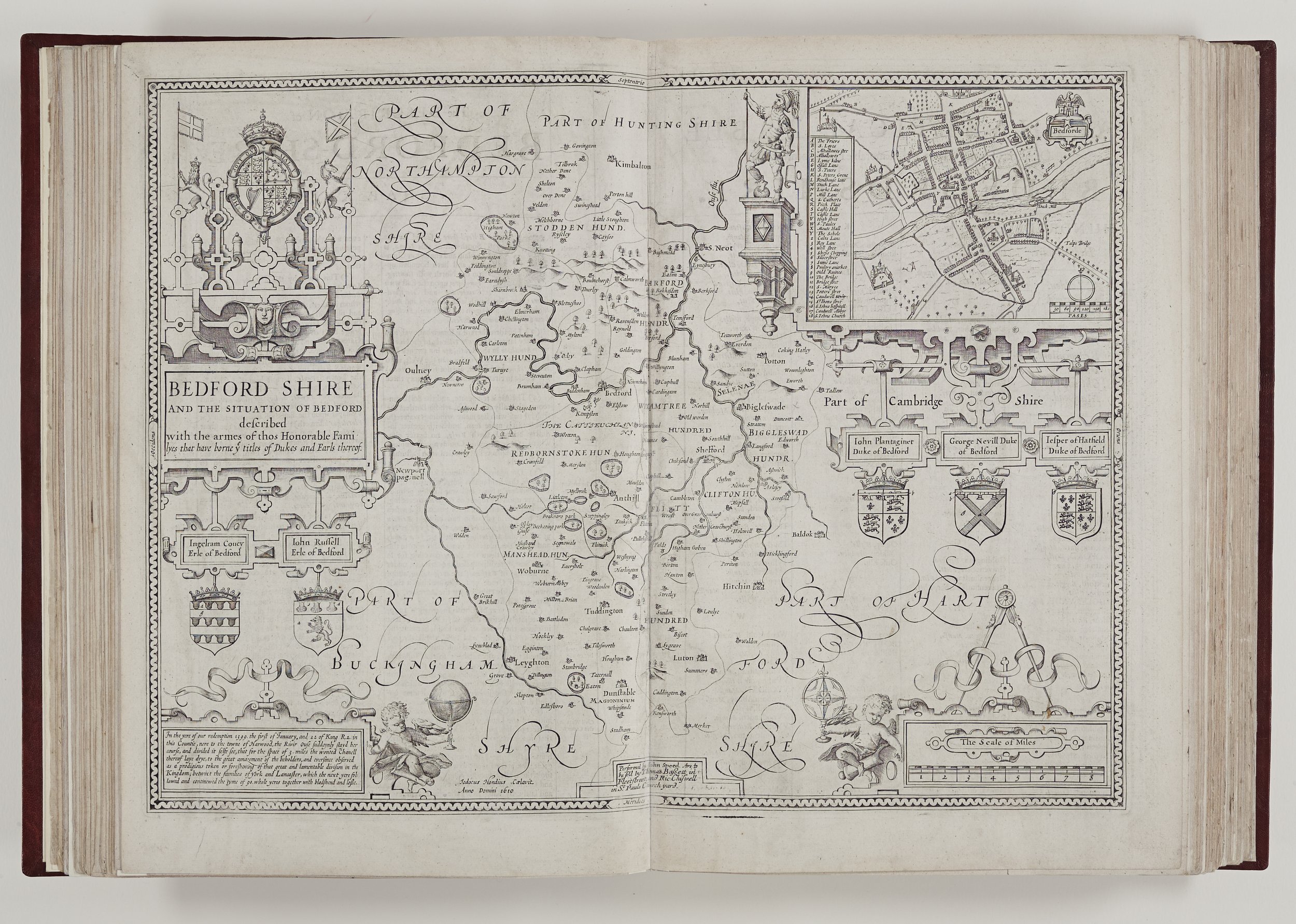

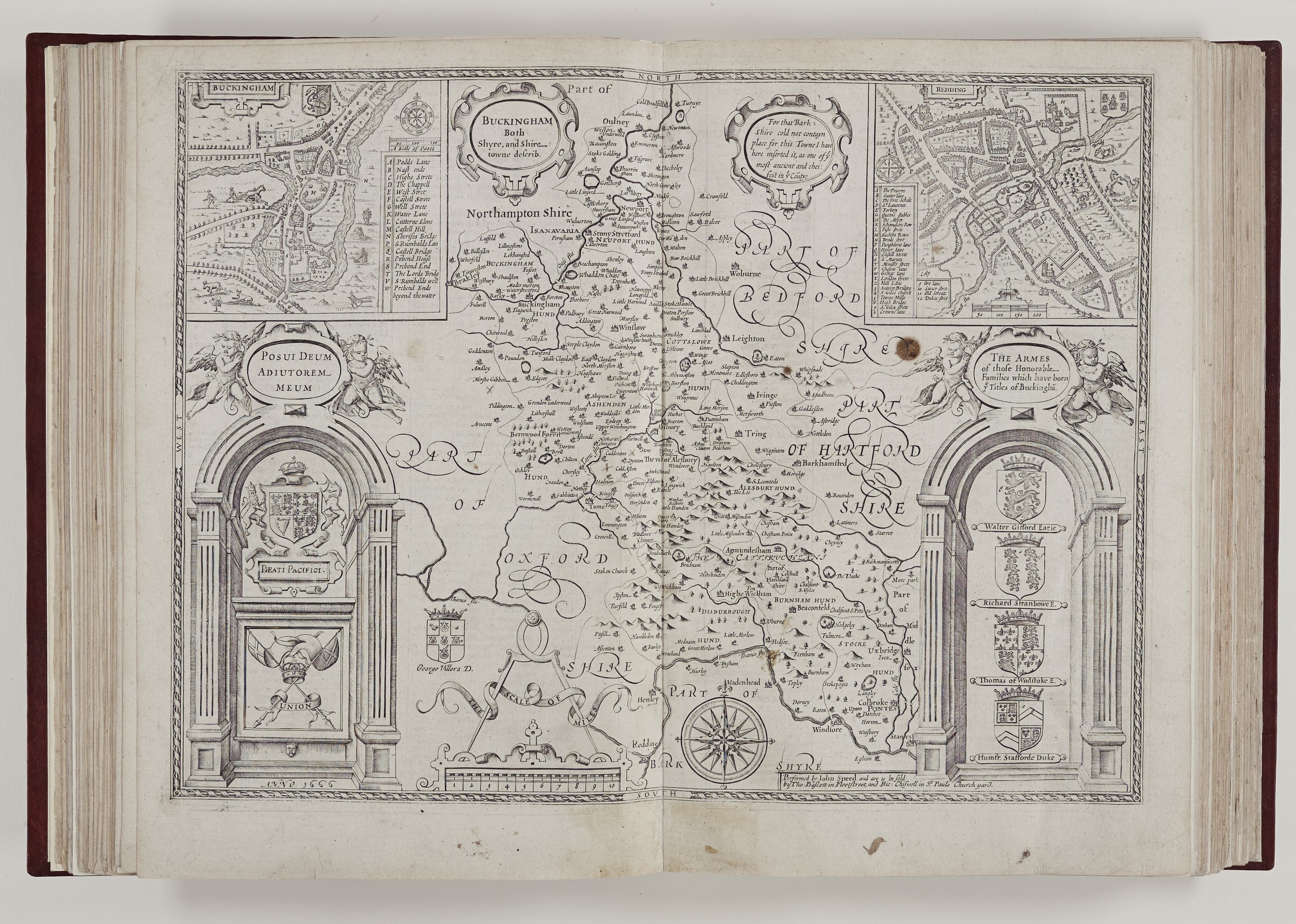

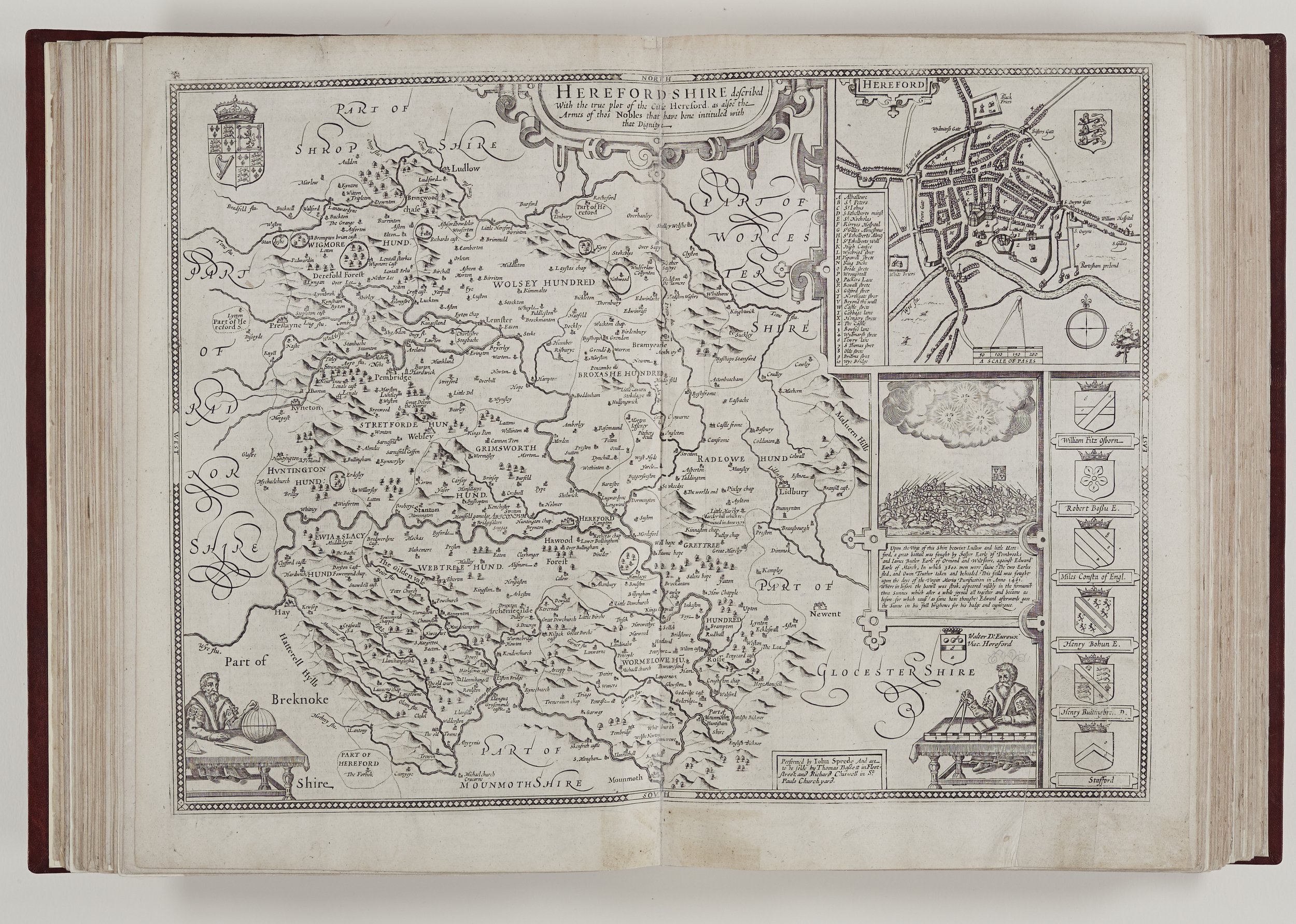

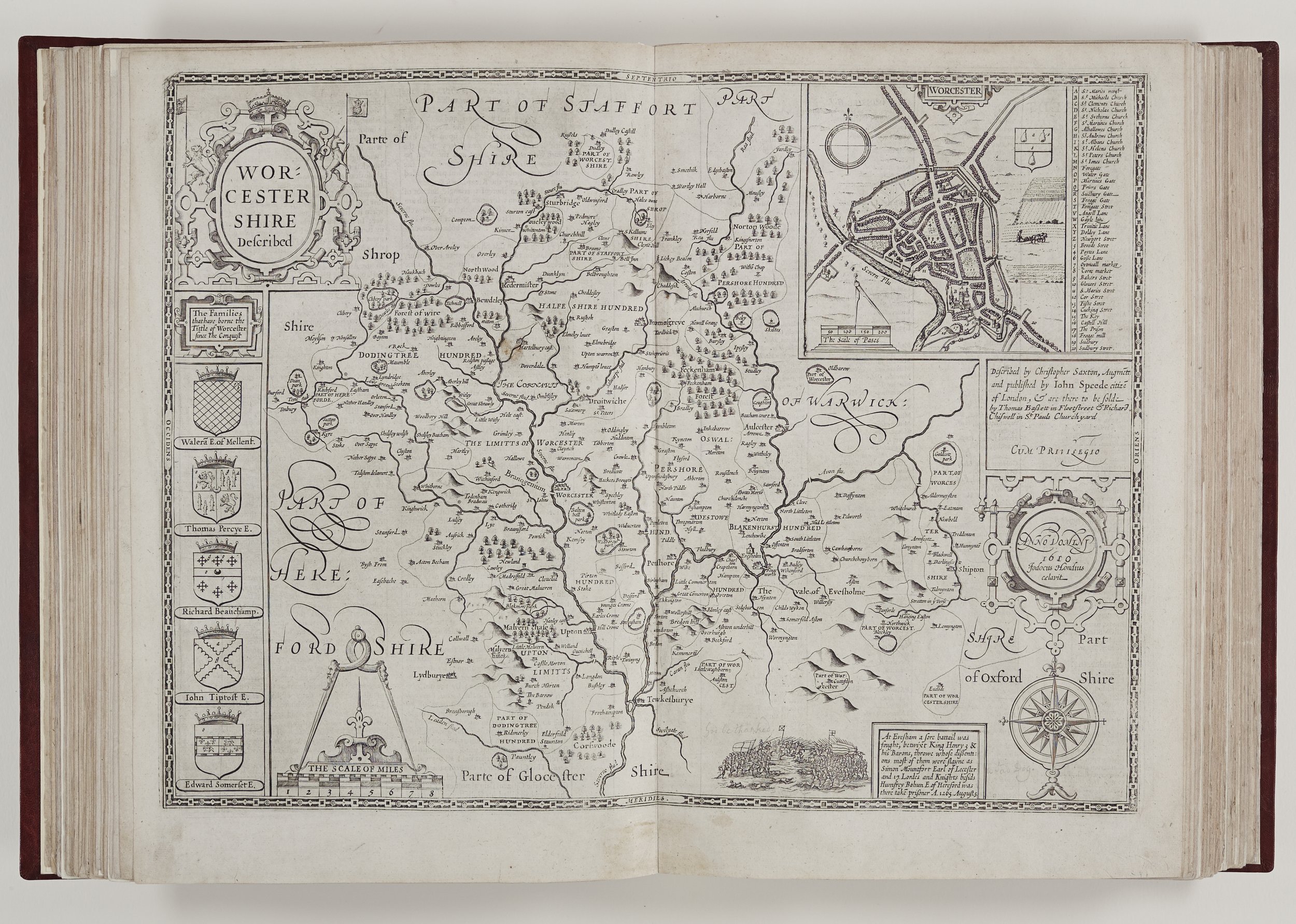

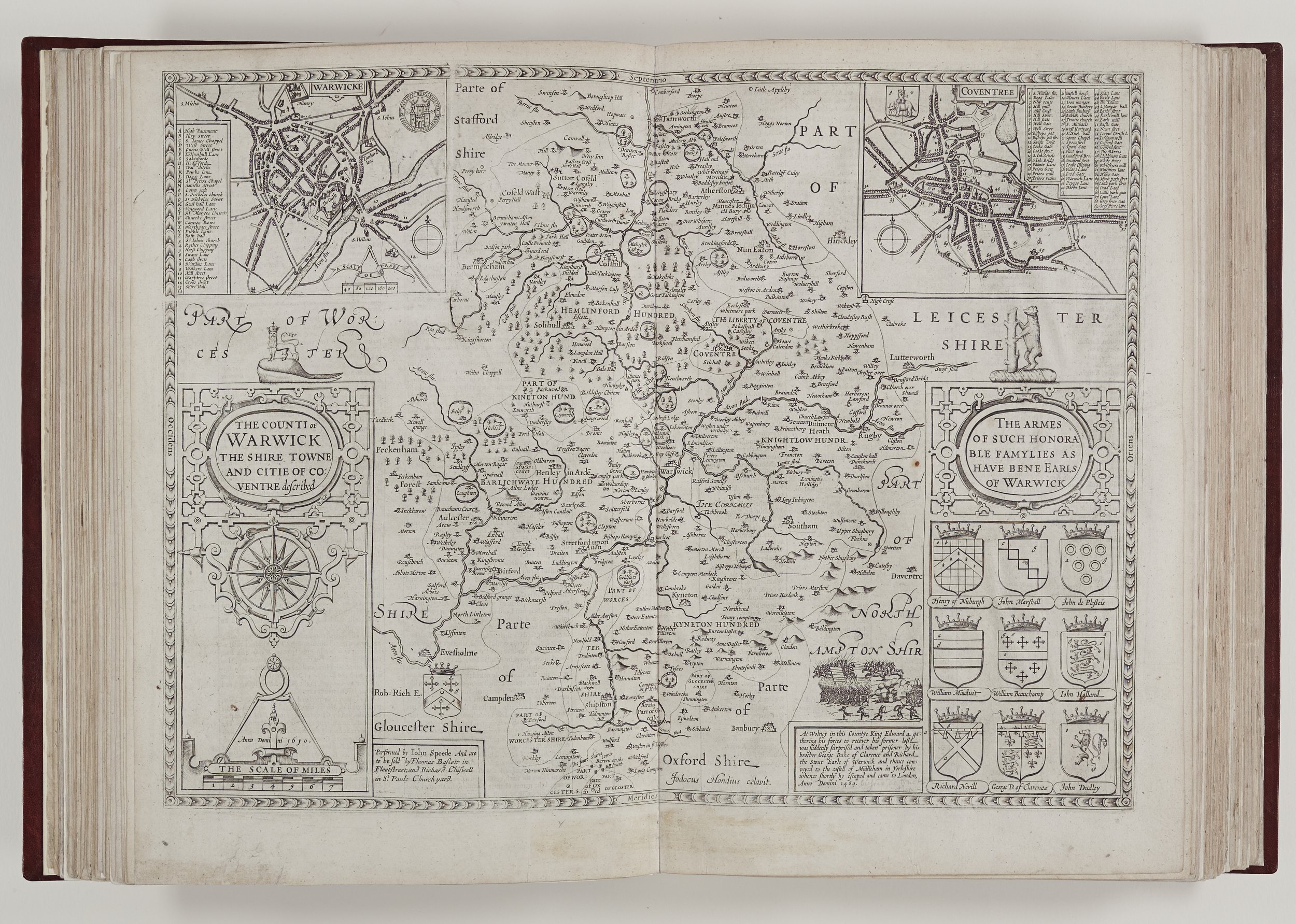

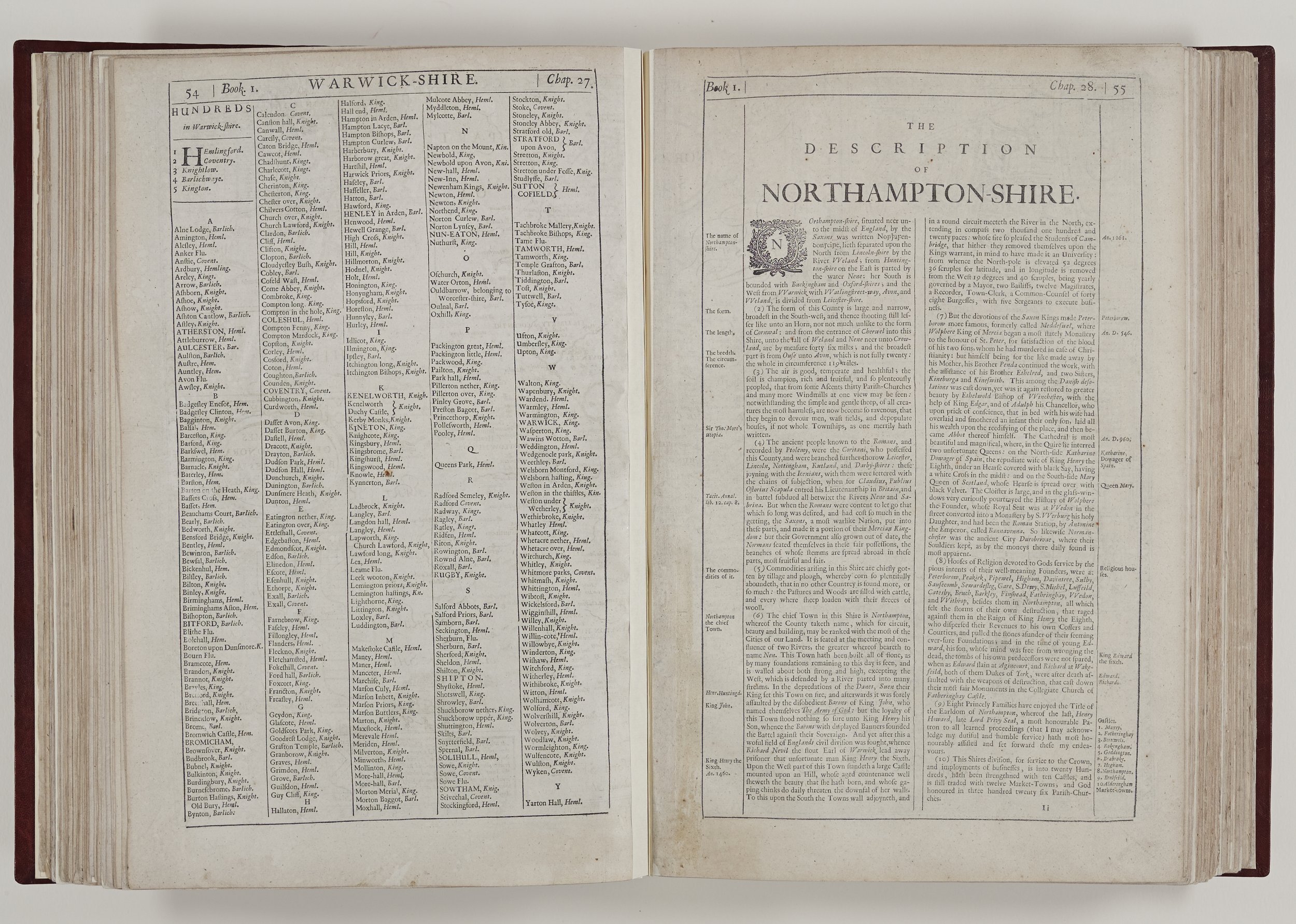

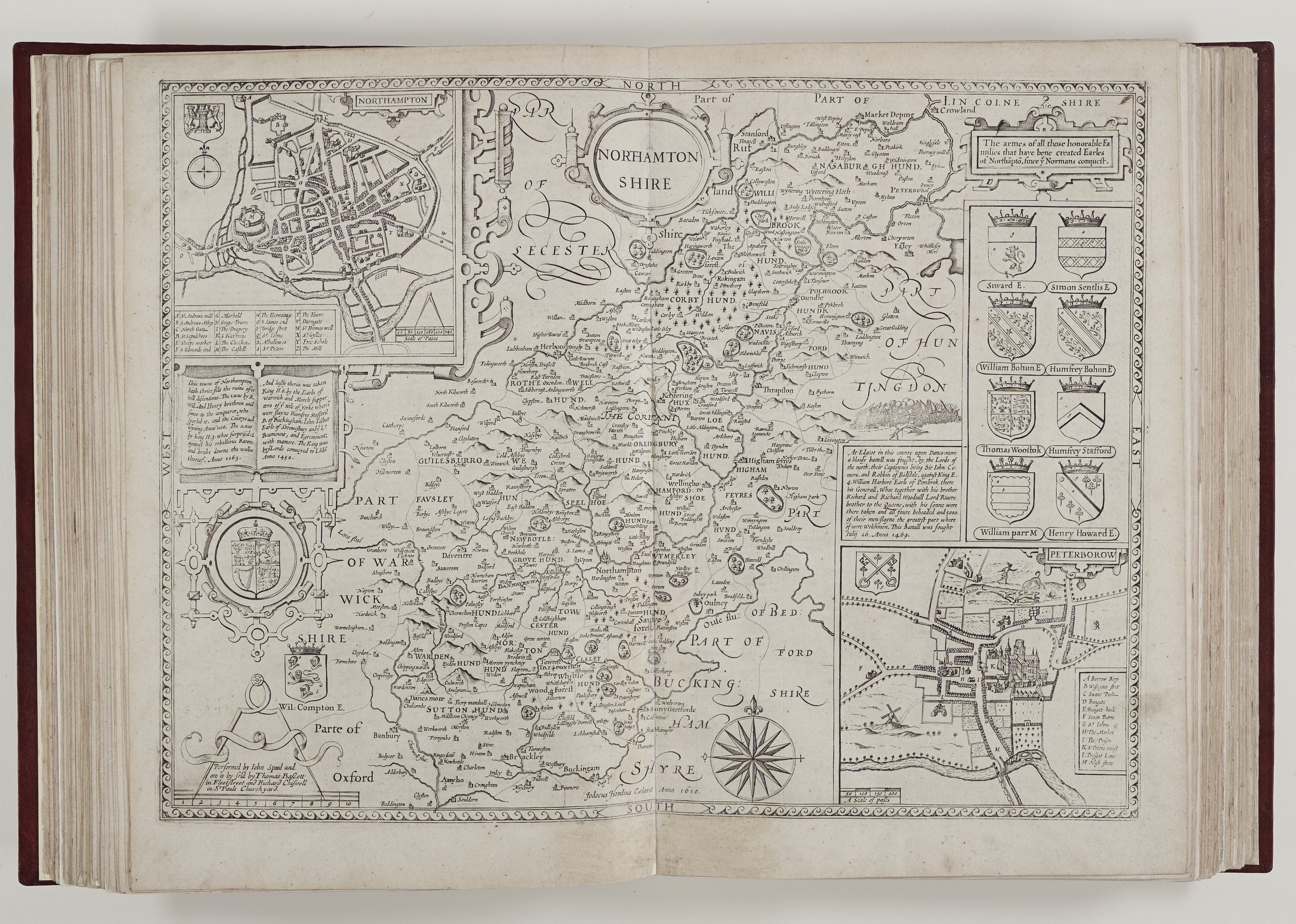

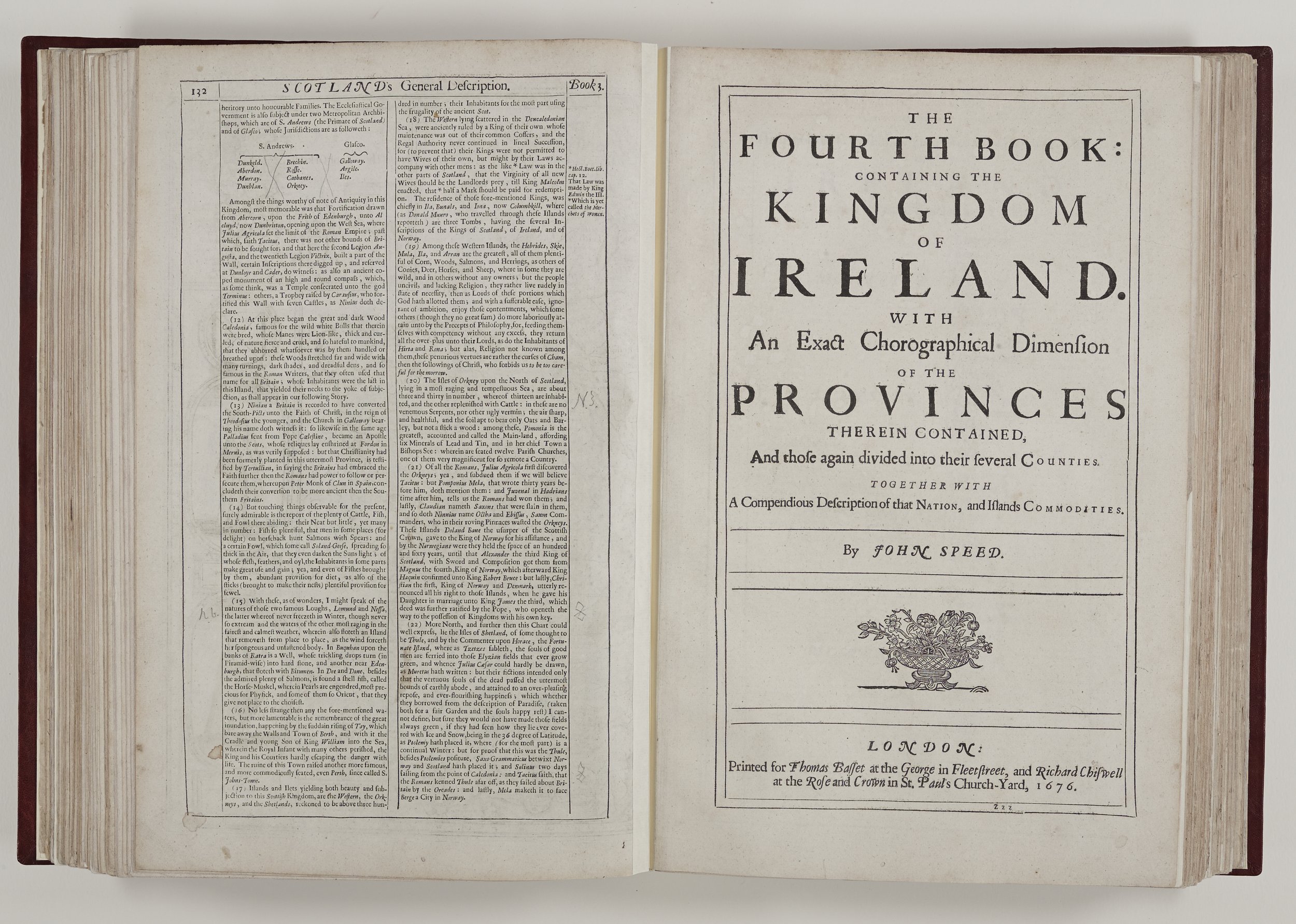

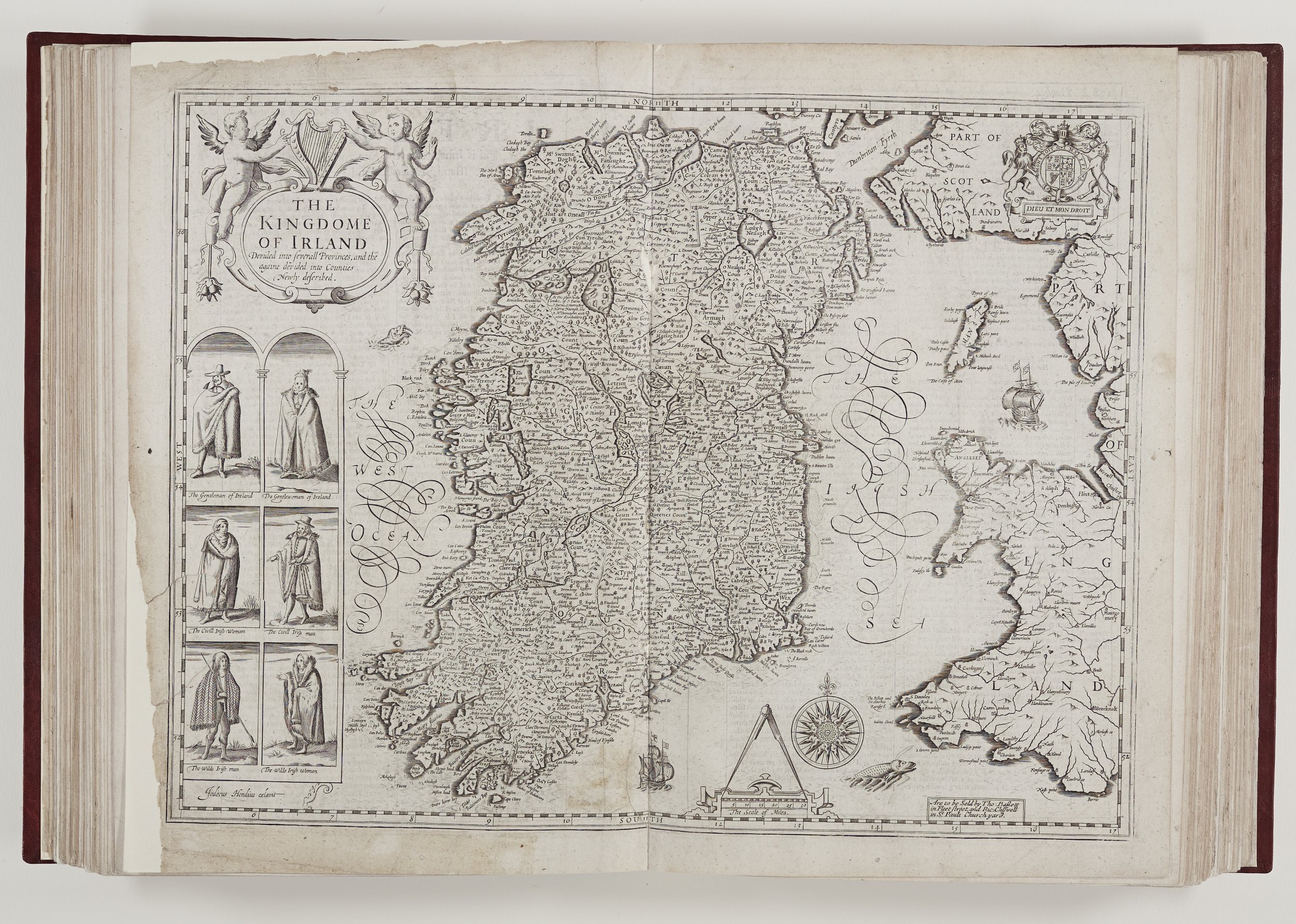

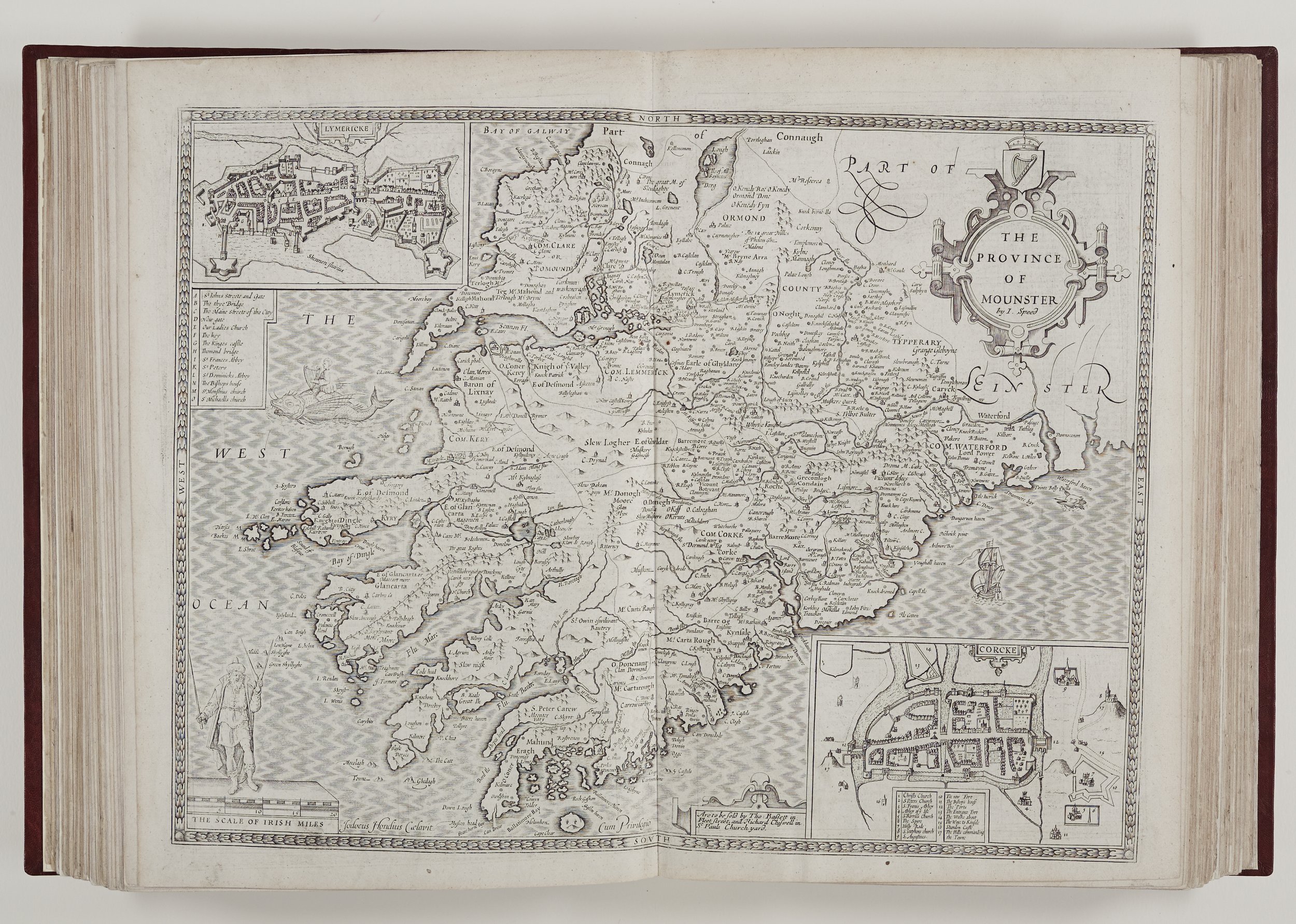

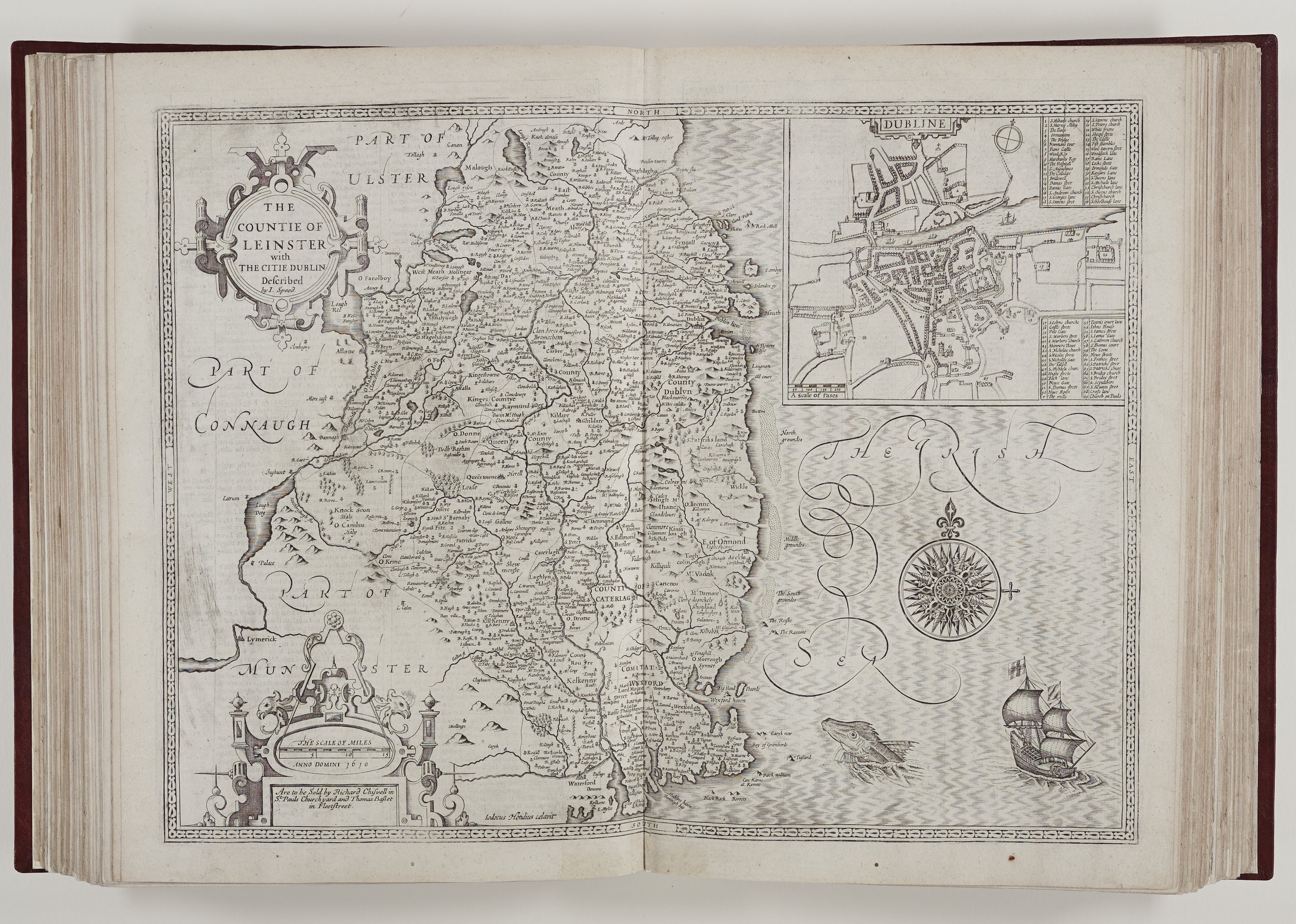

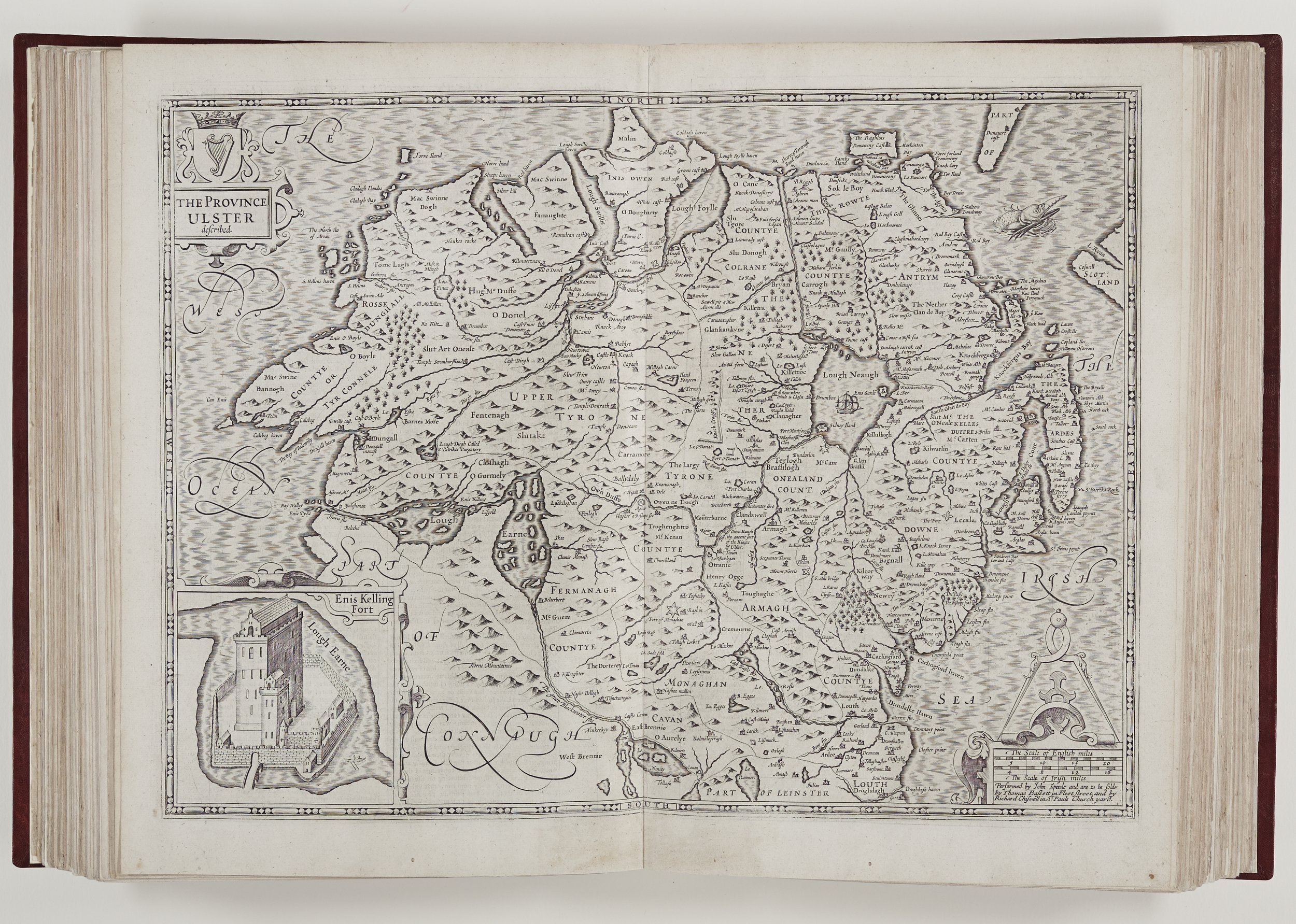

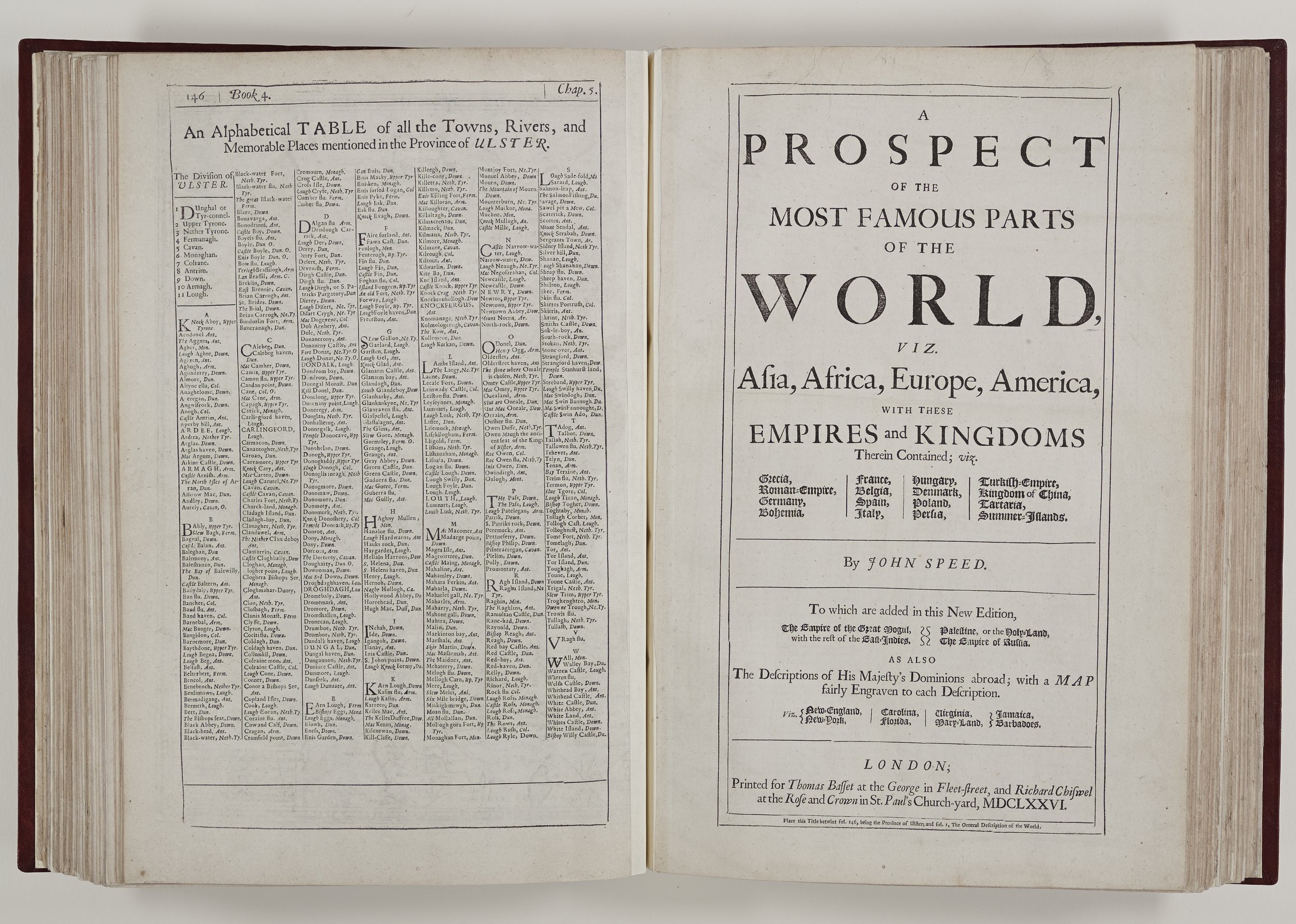

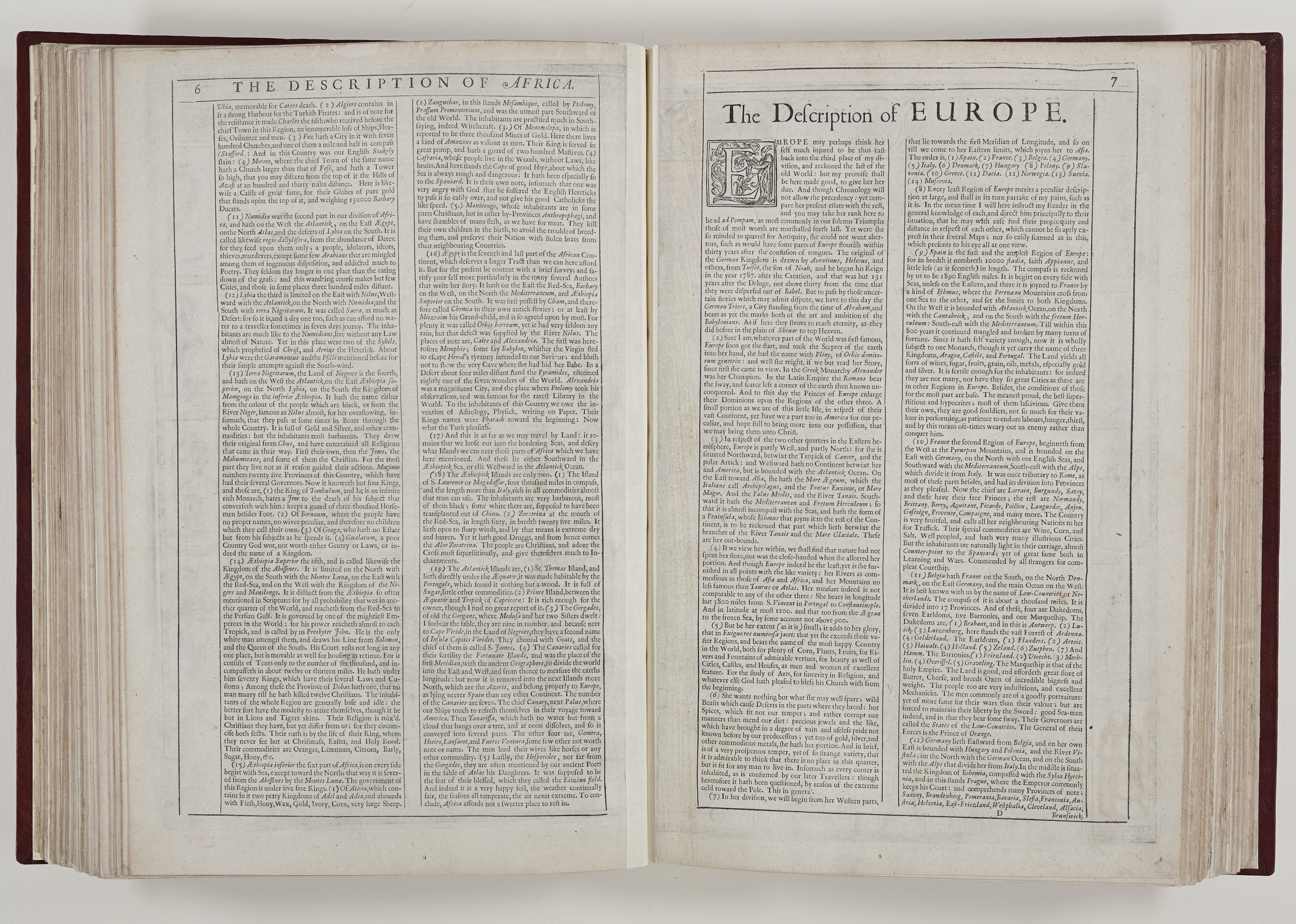

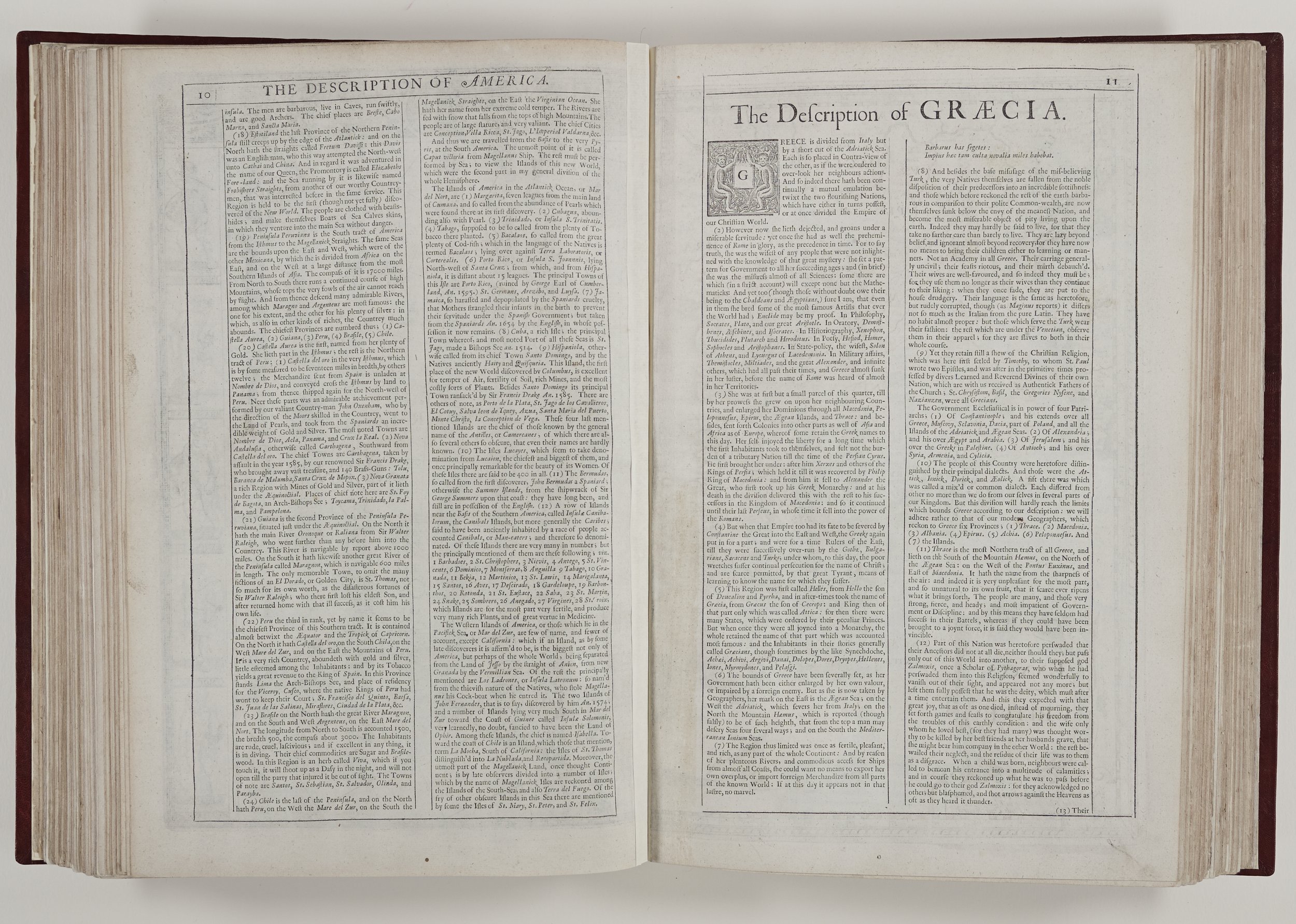

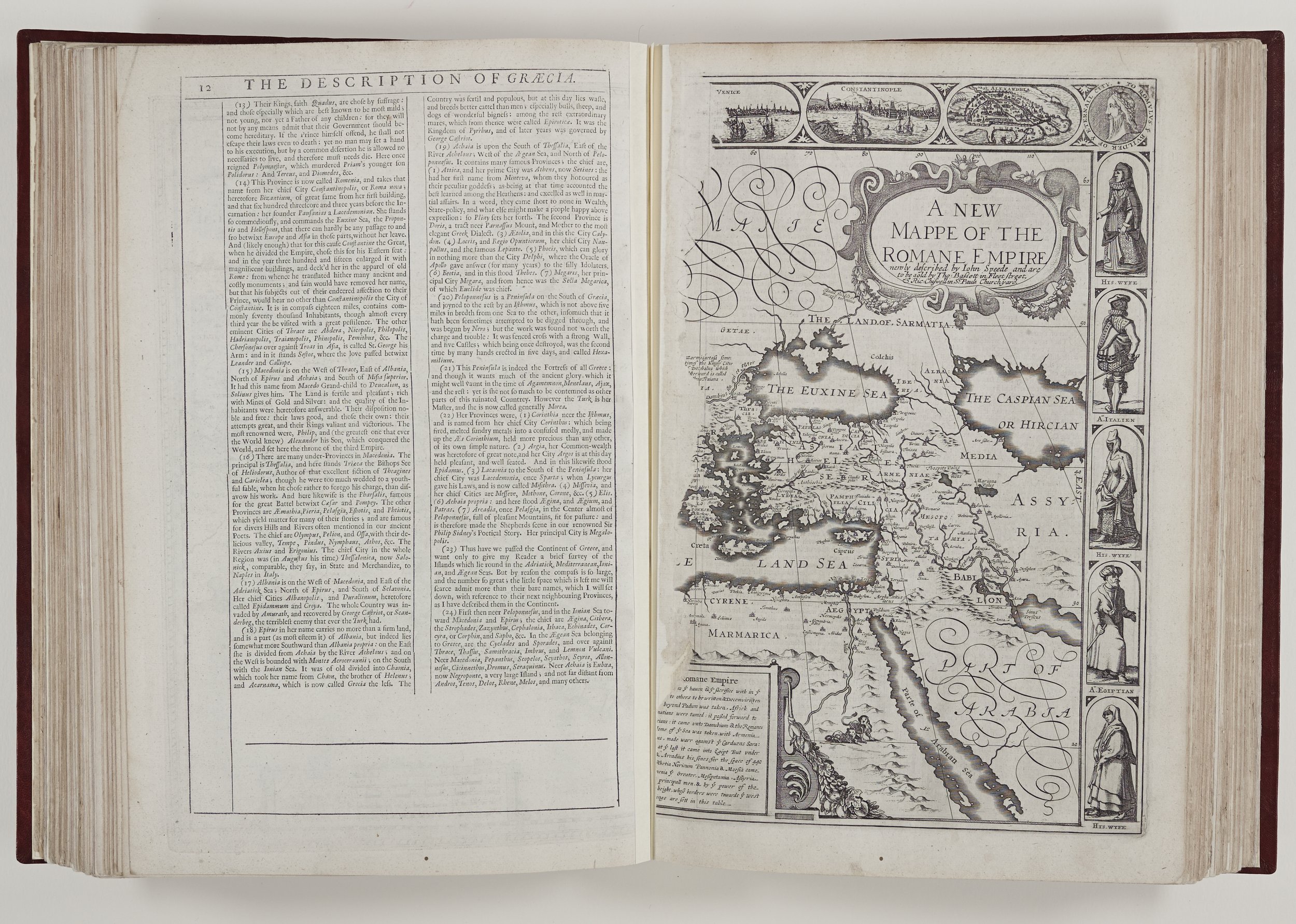

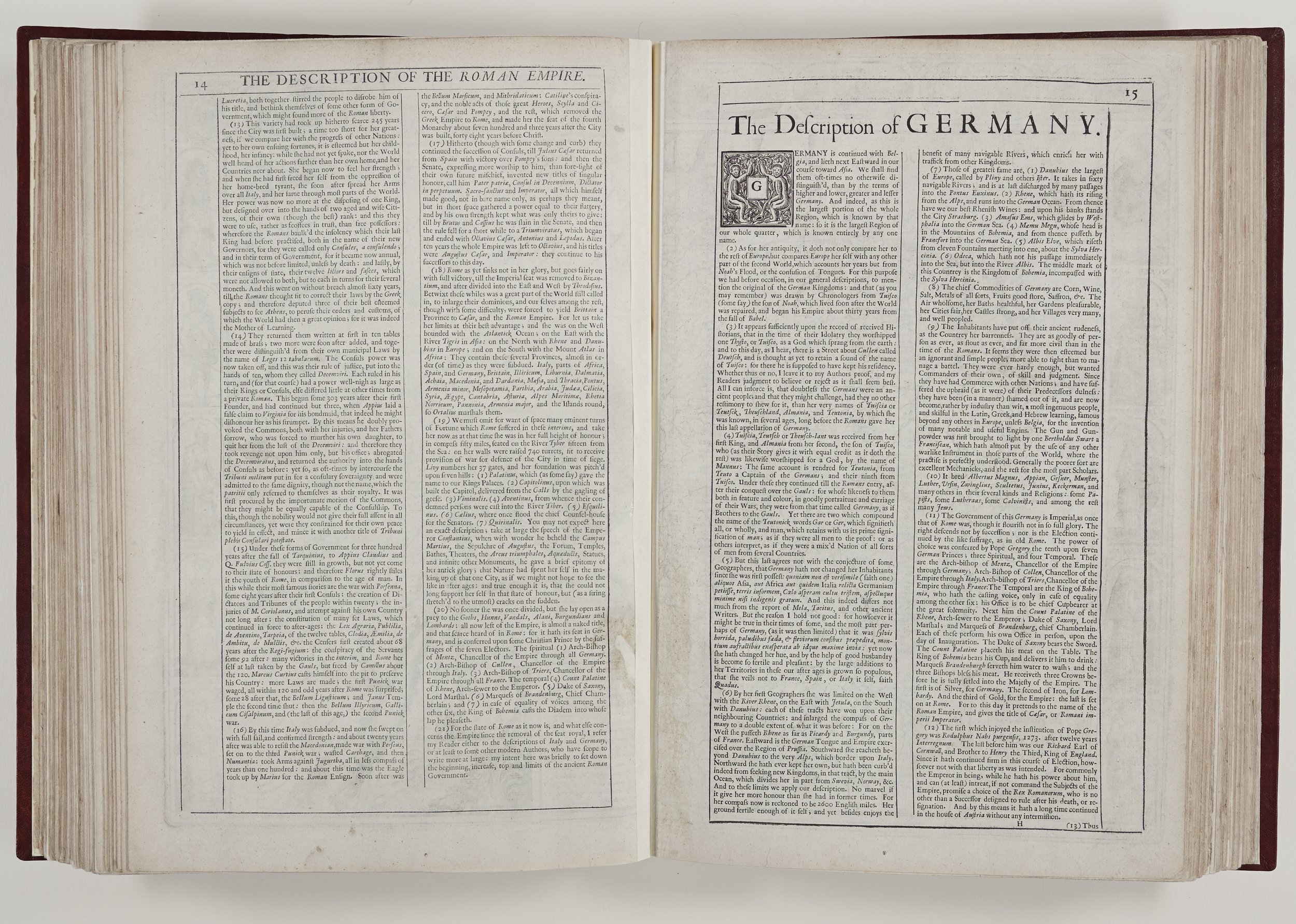

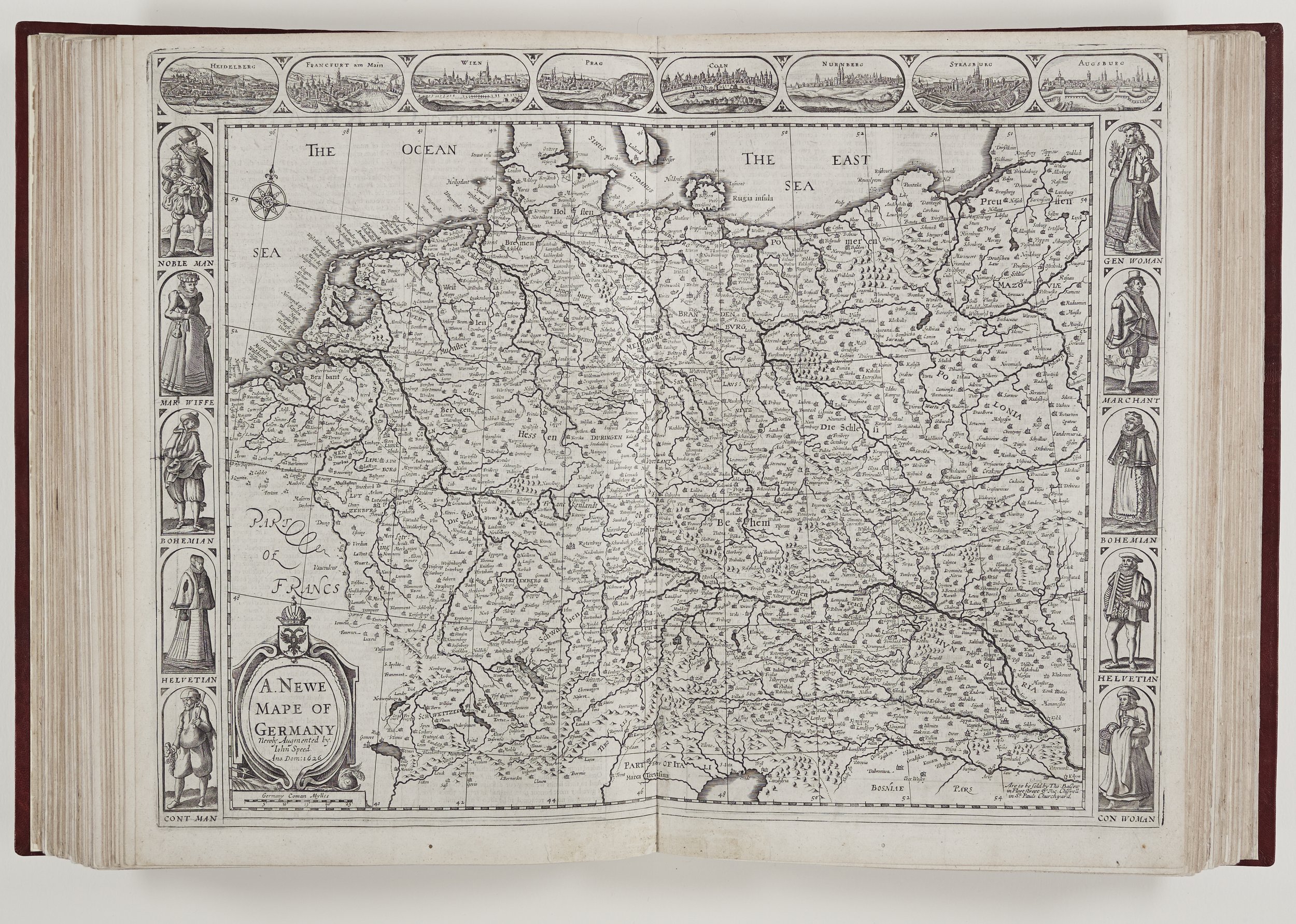

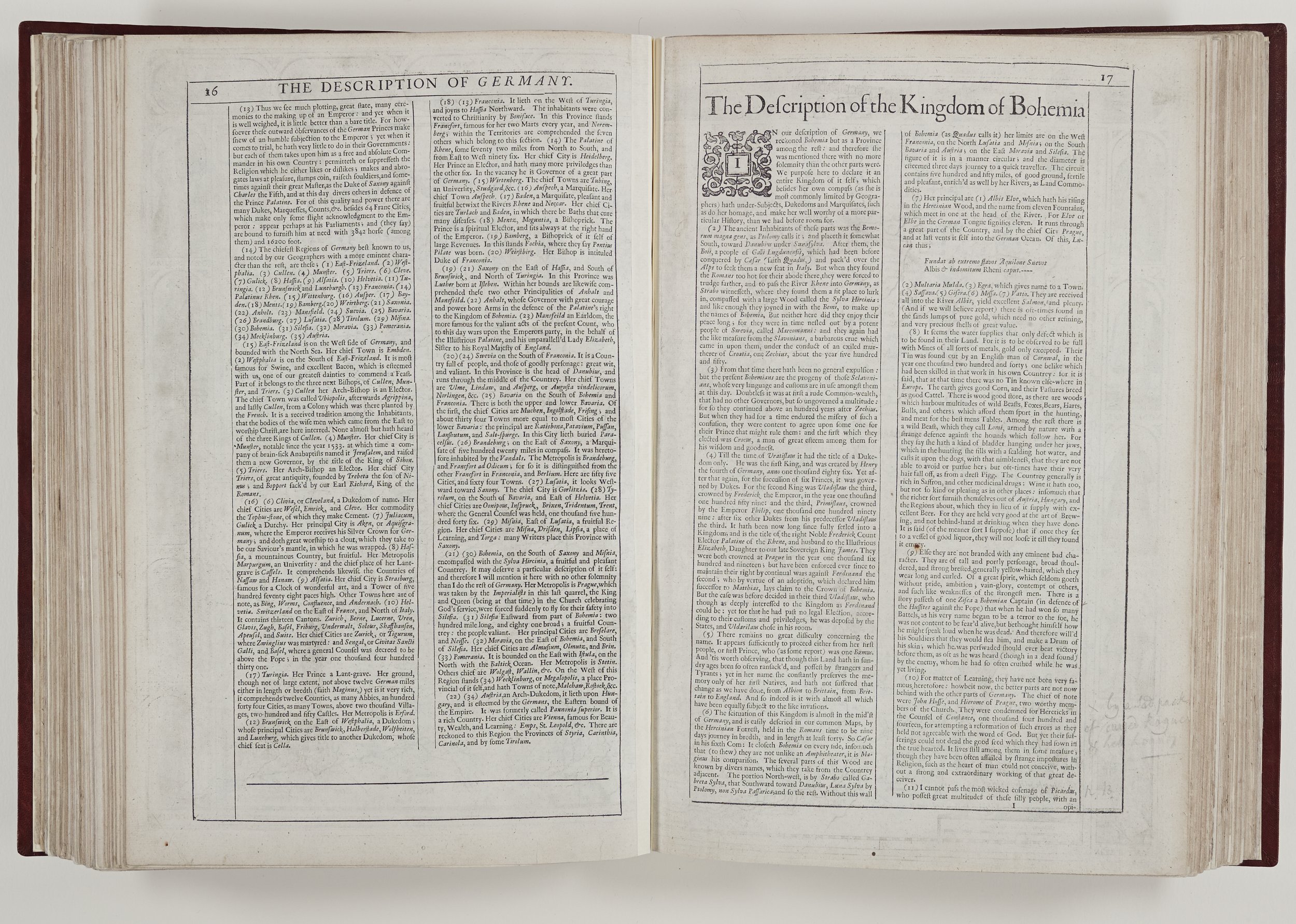

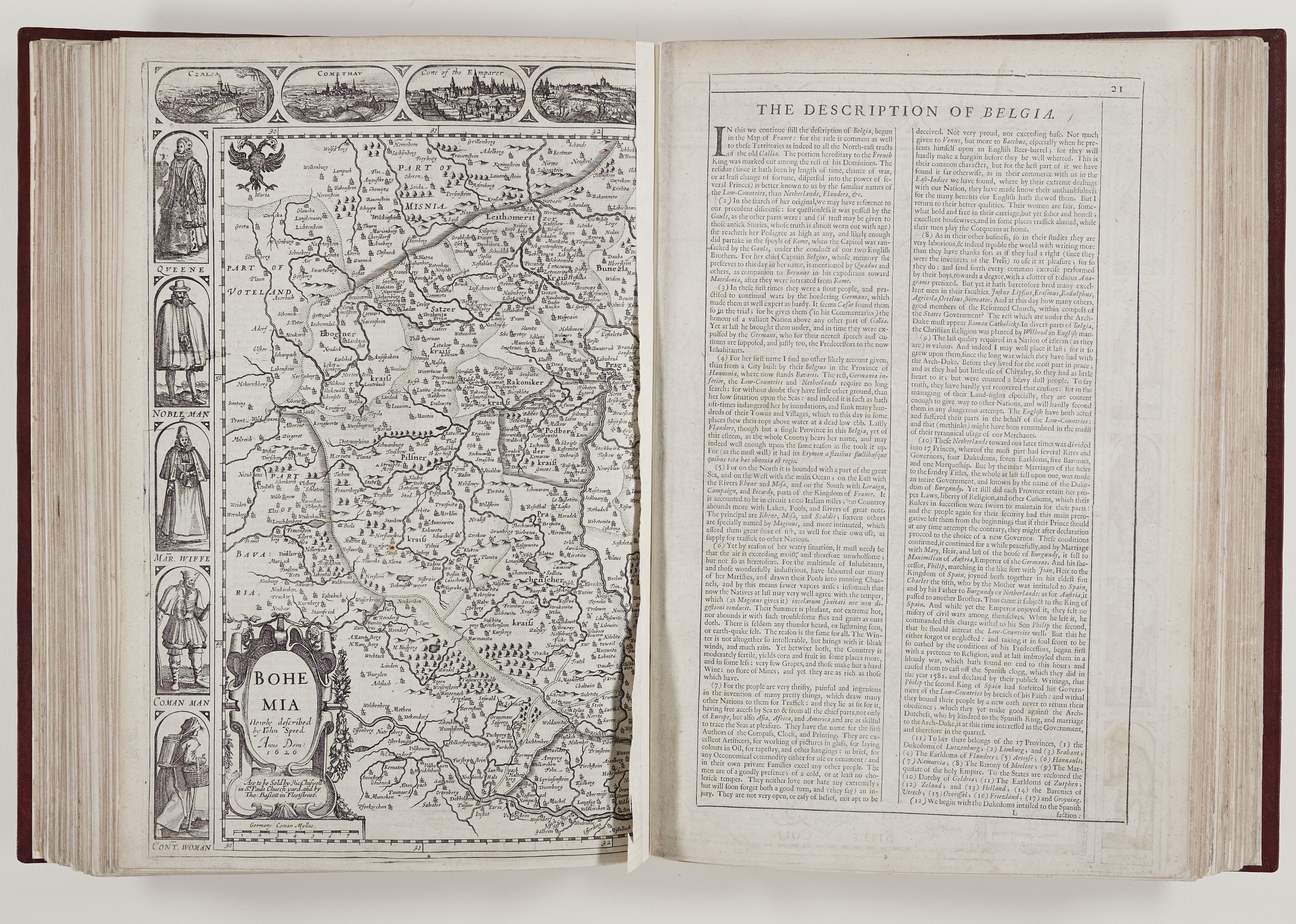

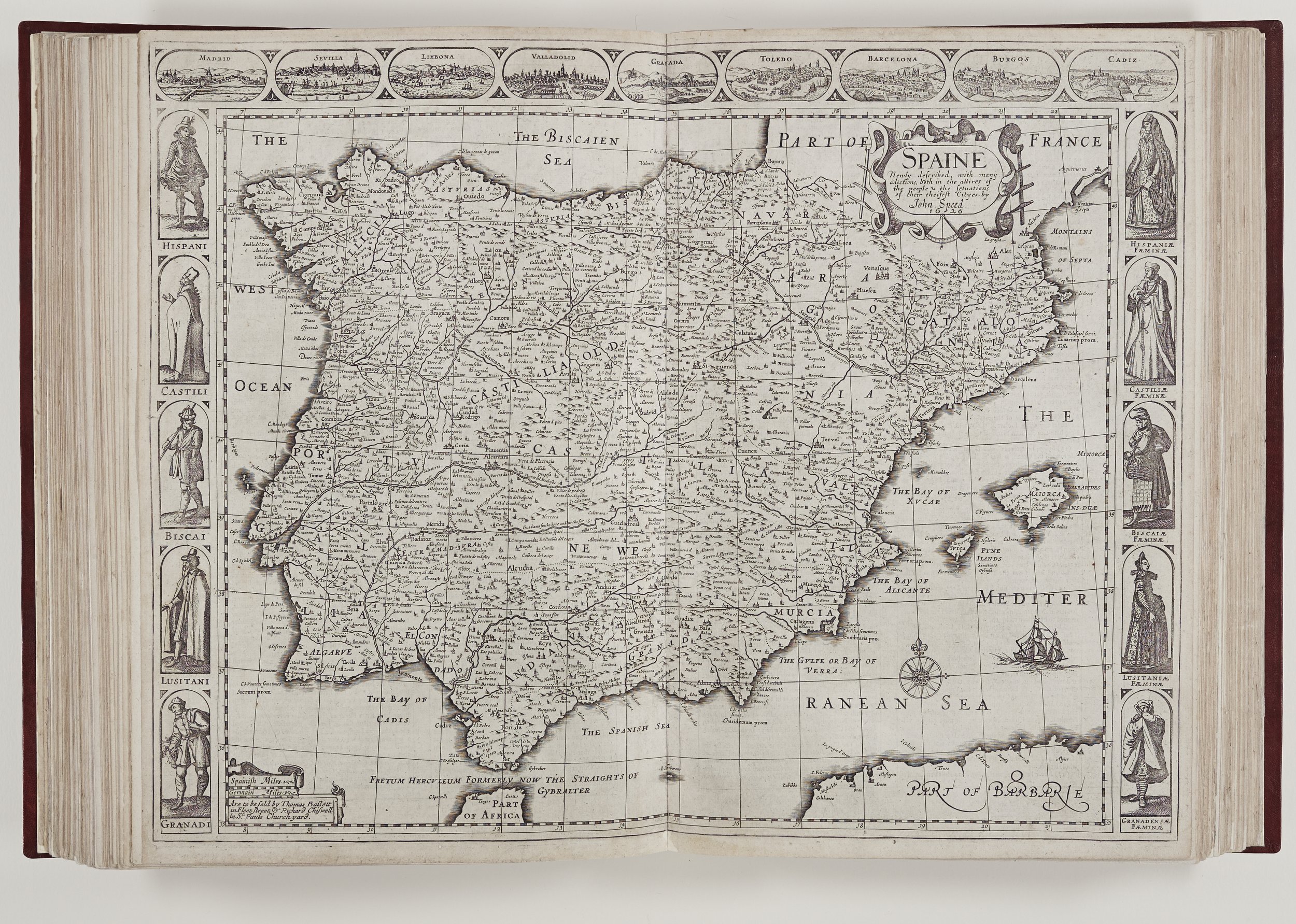

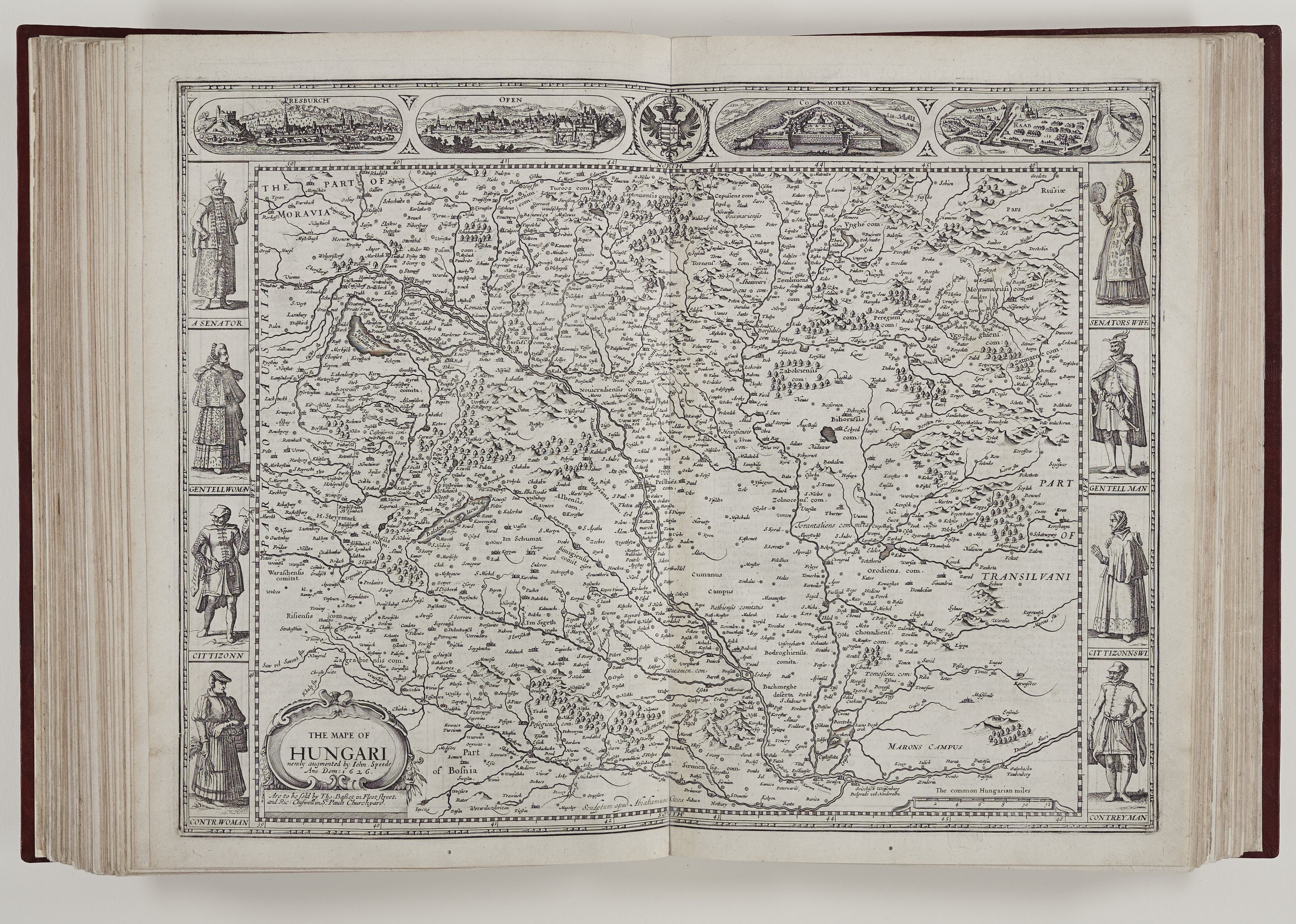

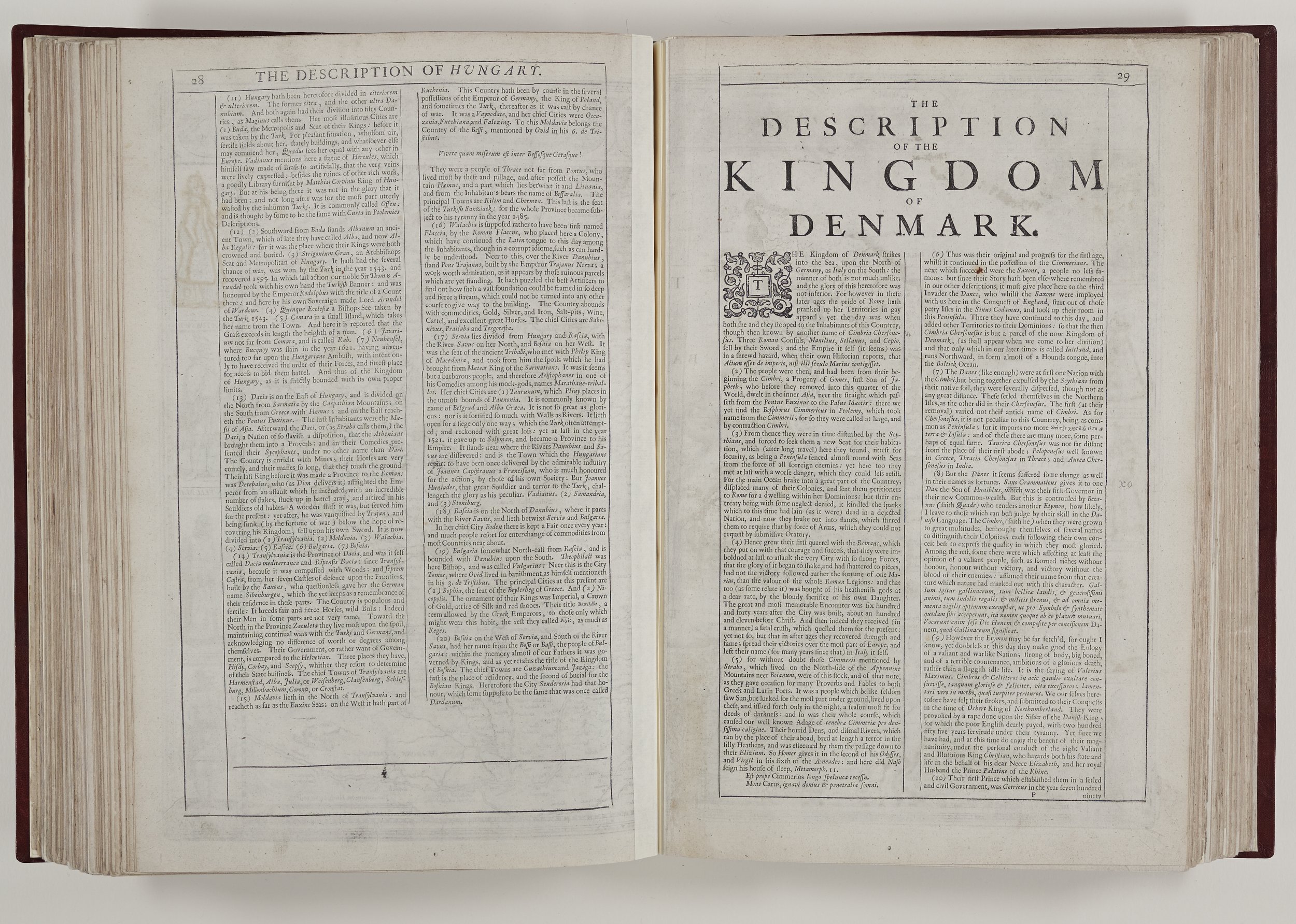

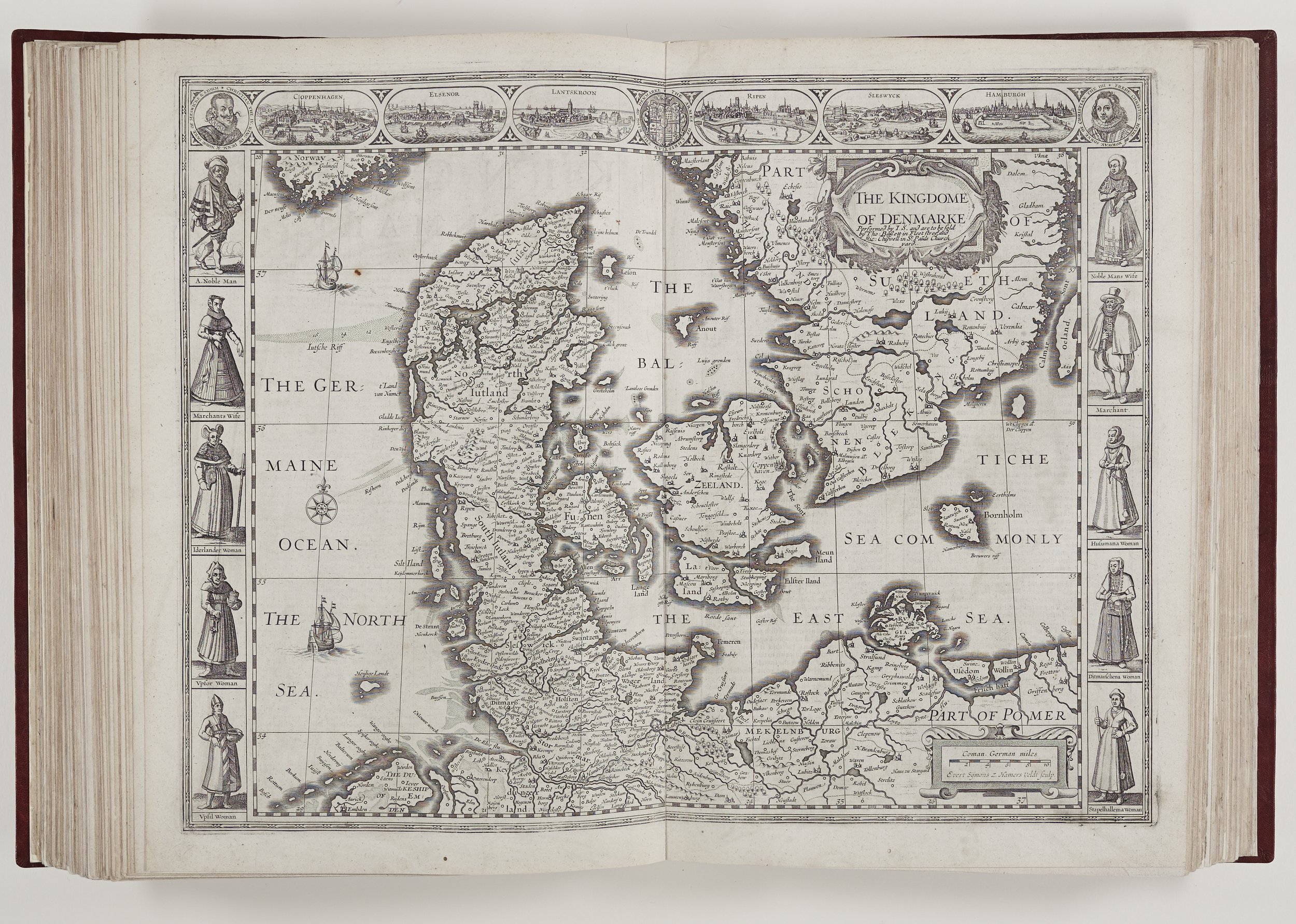

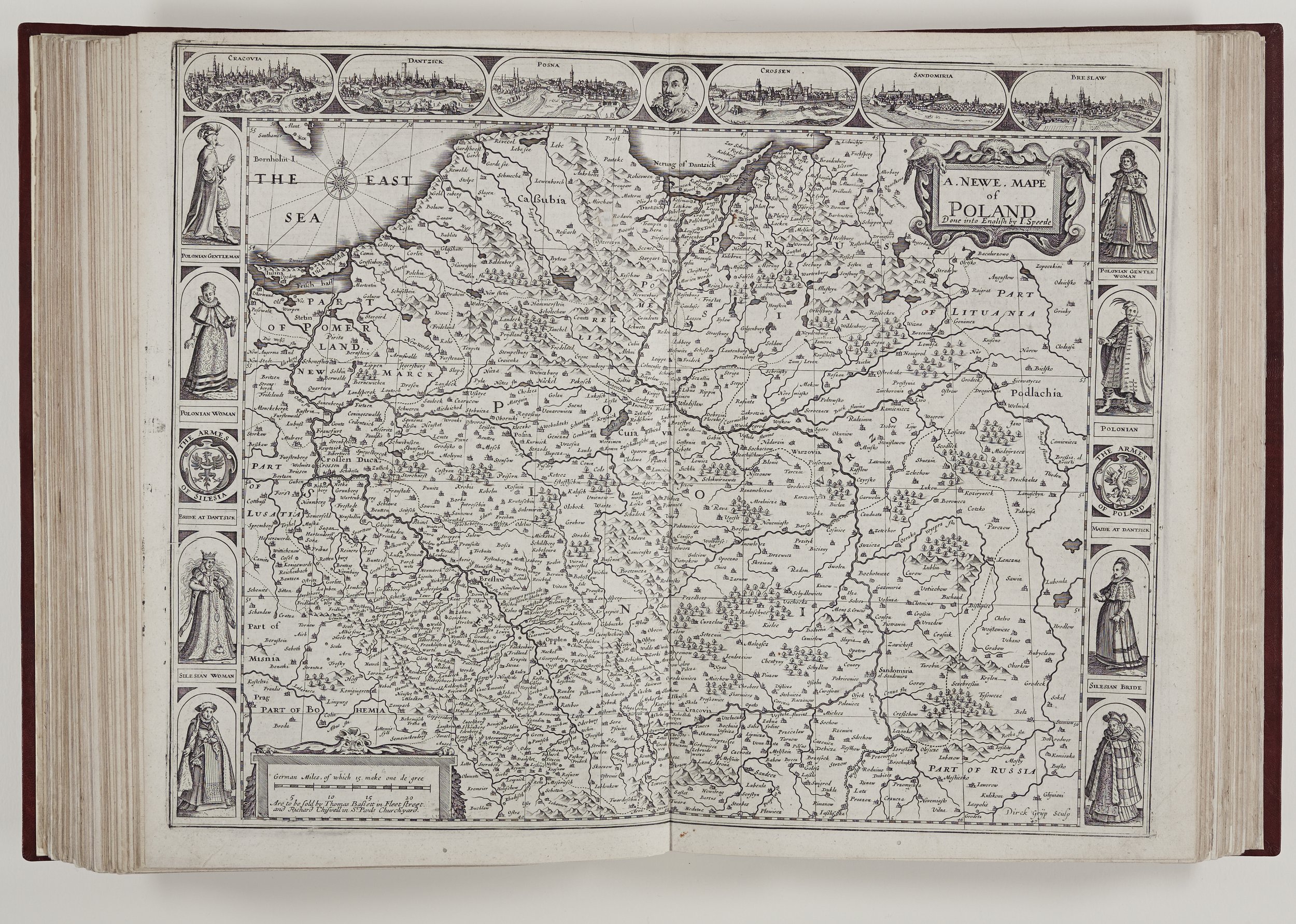

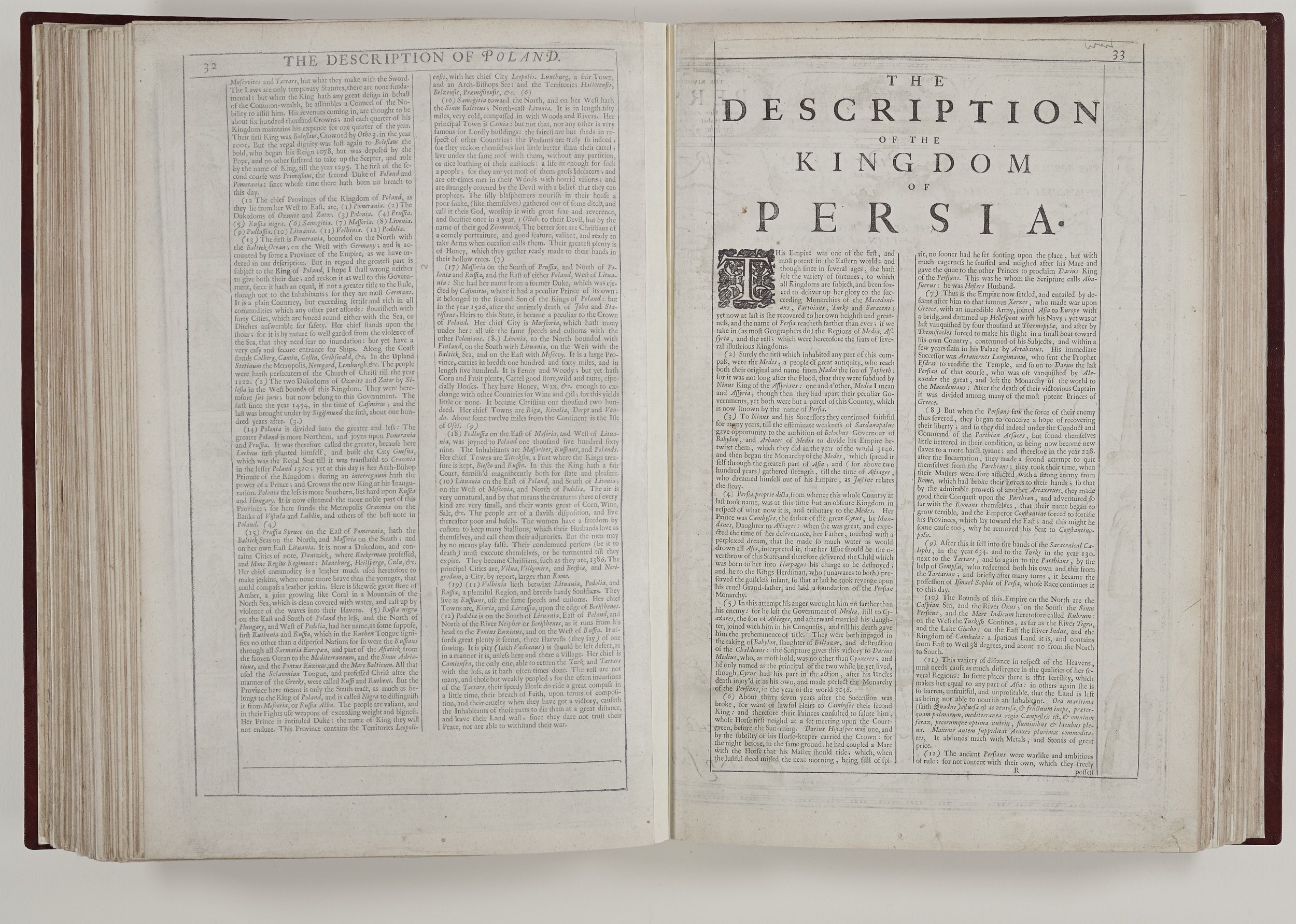

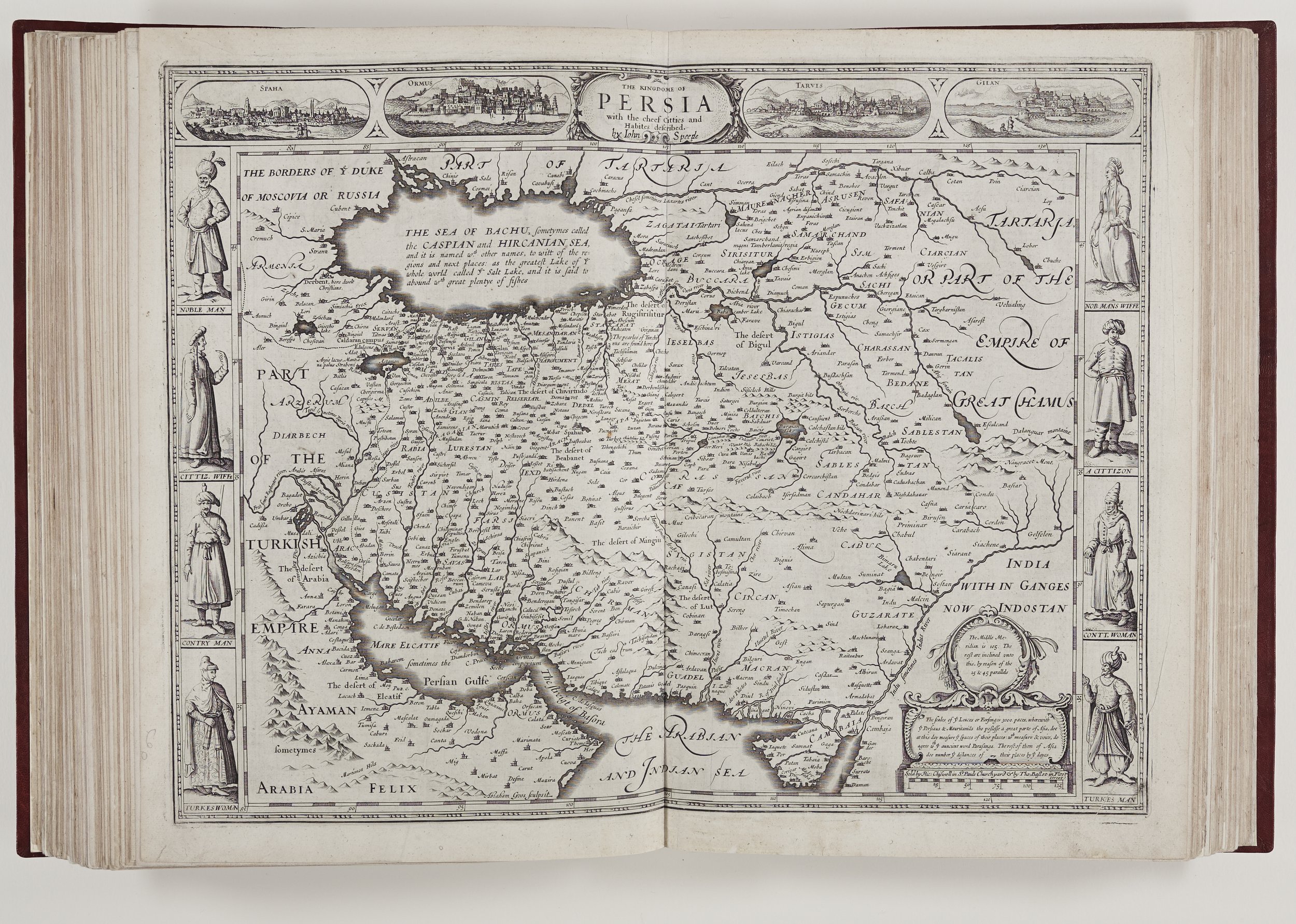

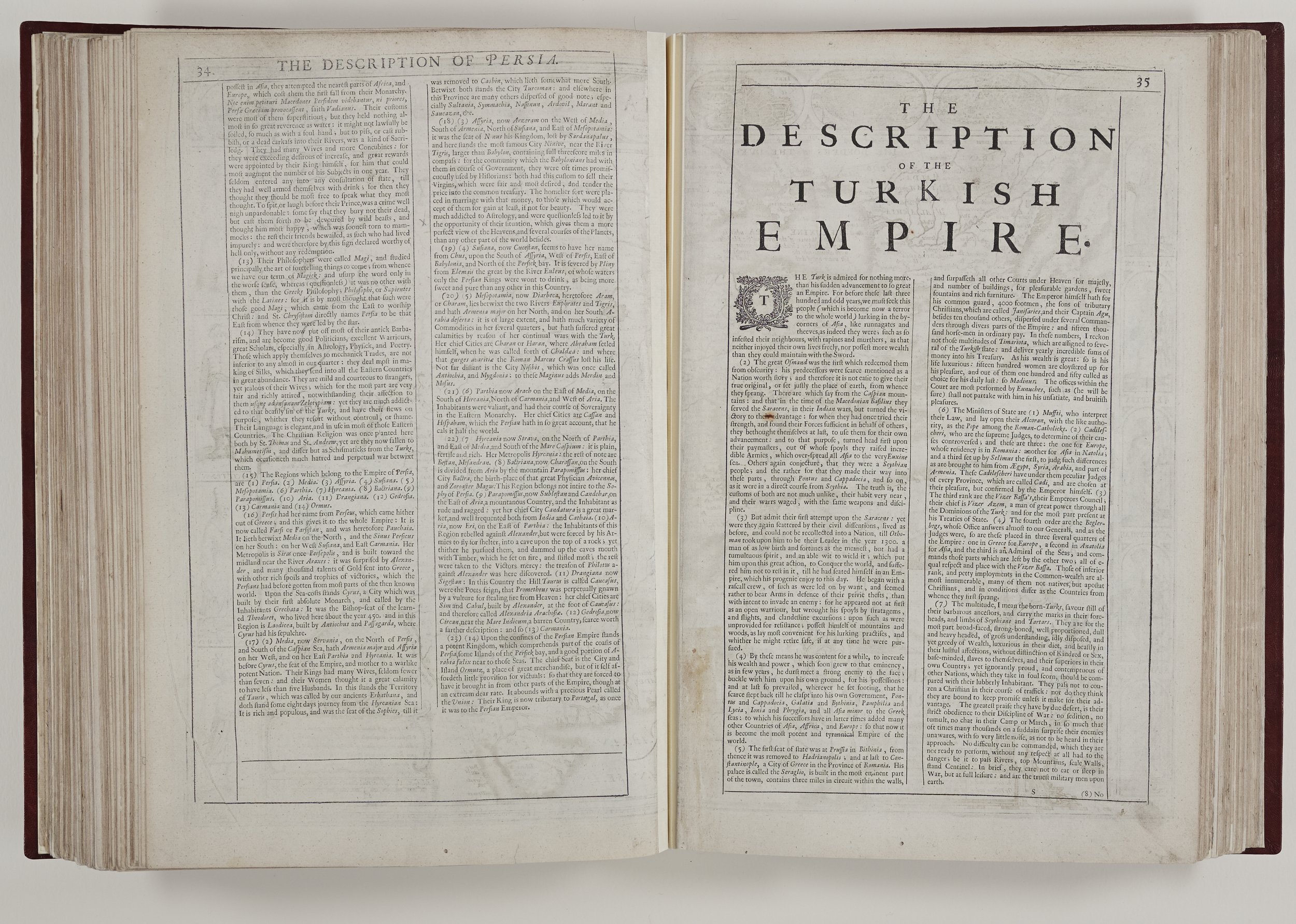

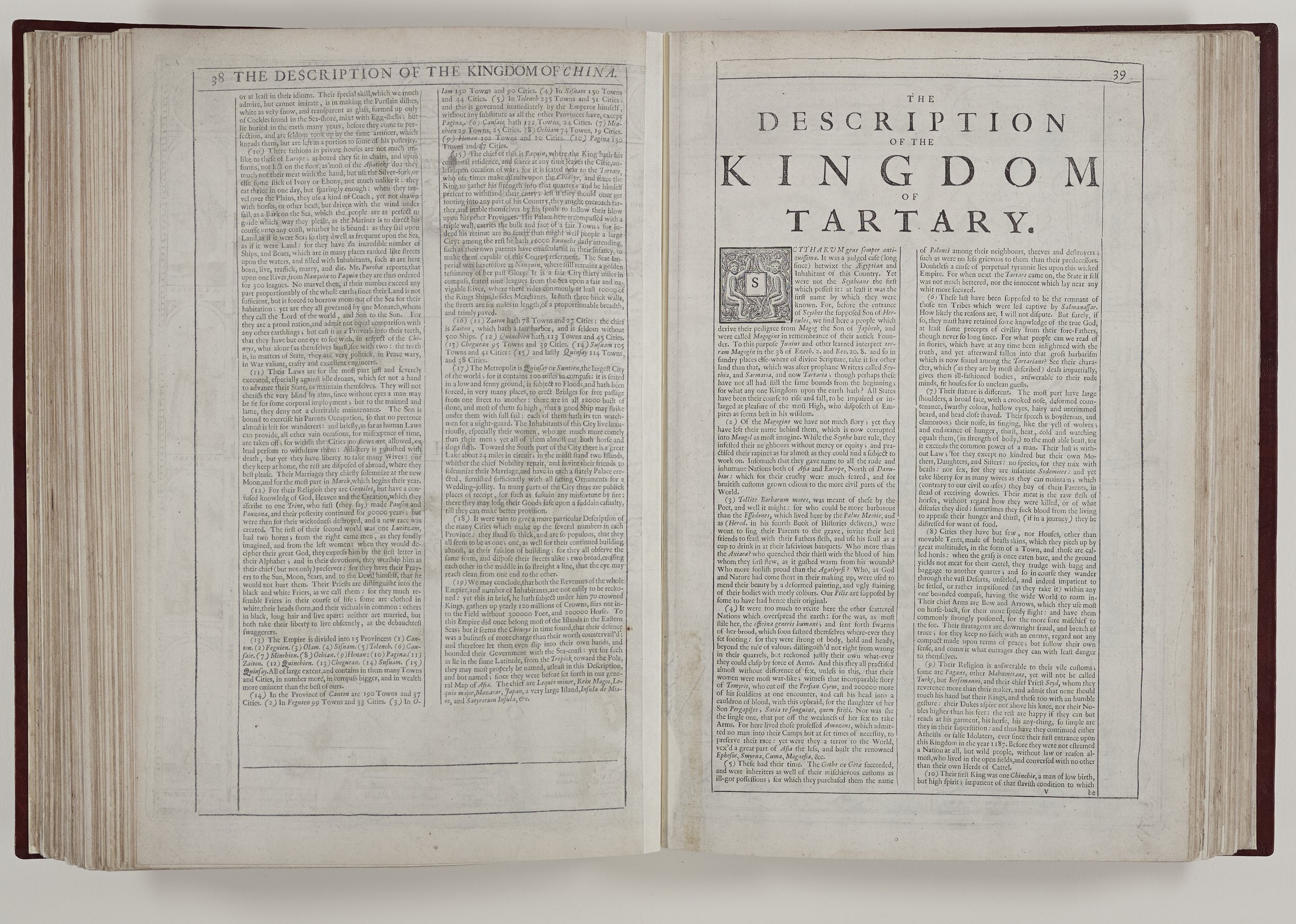

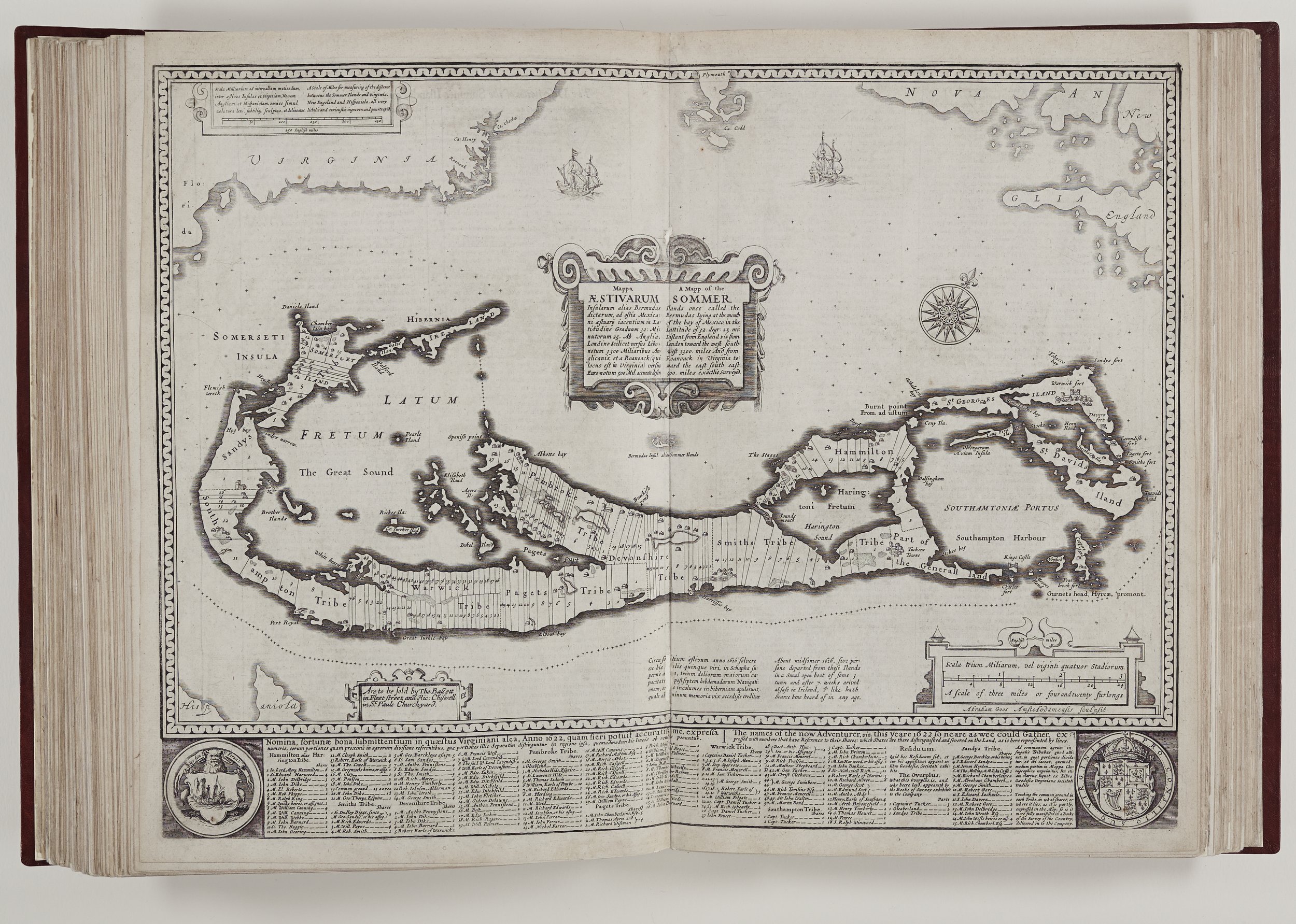

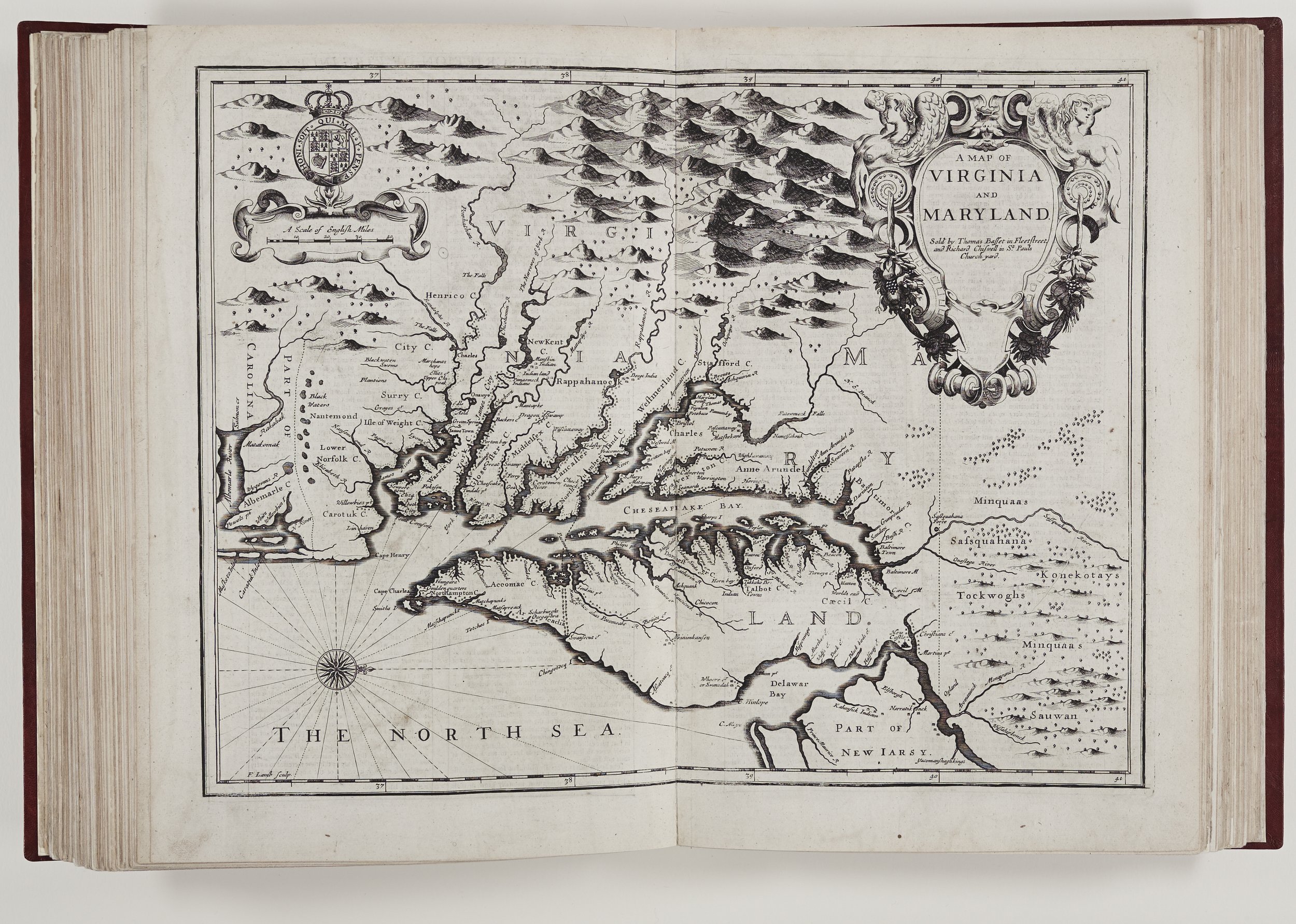

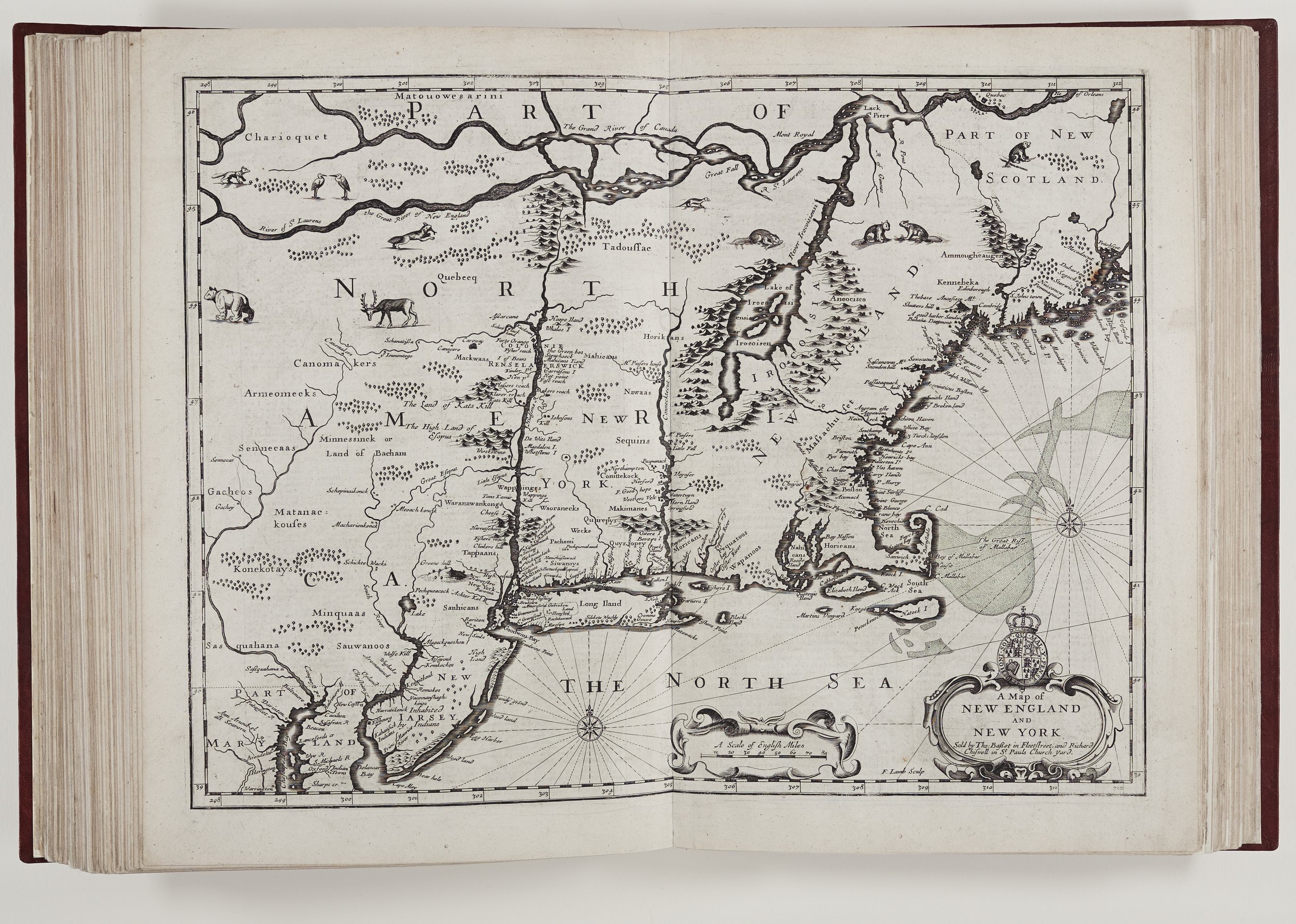

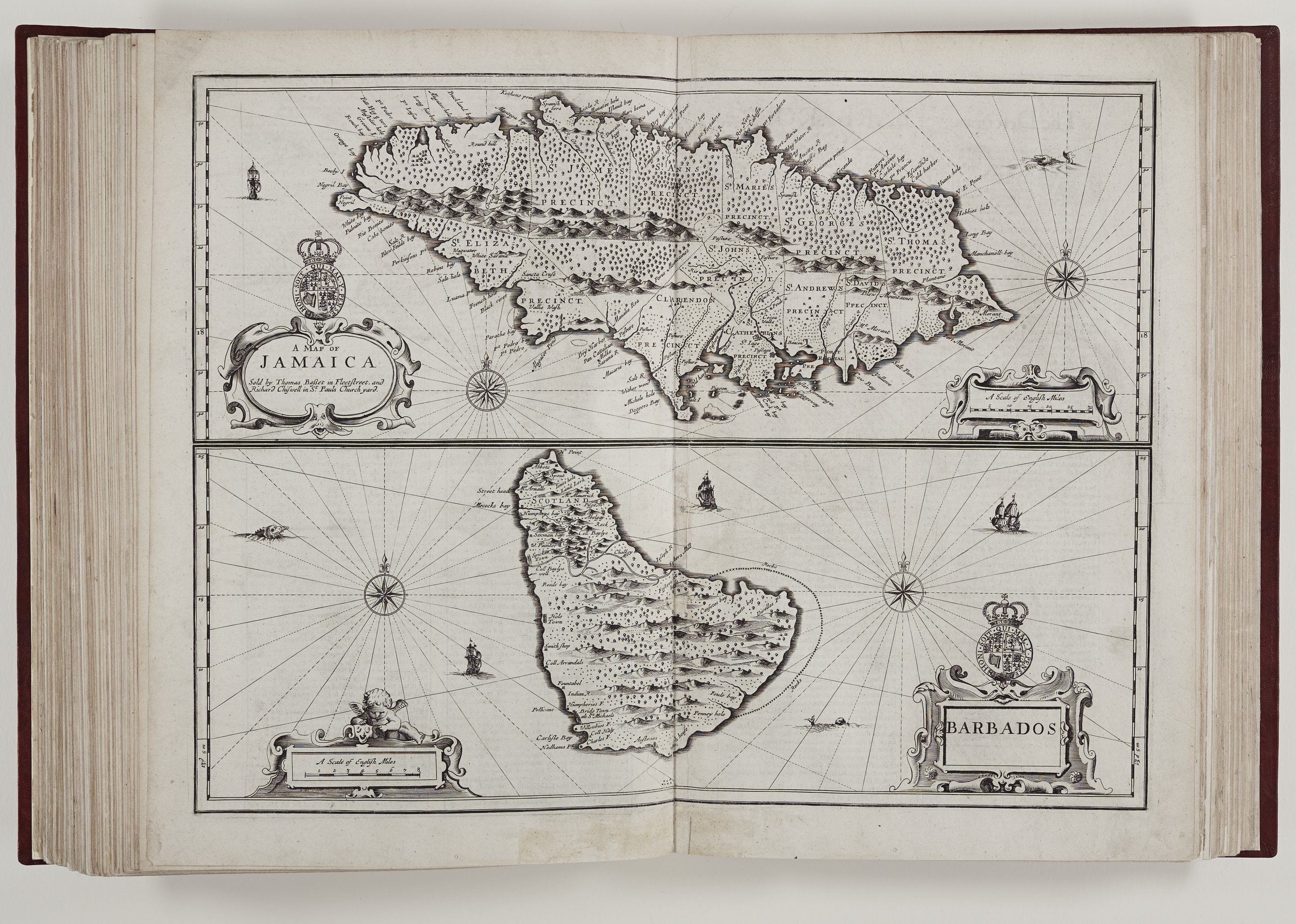

Speed’s foremost intention was to write a History of Great Britain and to produce an atlas as a companion volume but it is the latter which has established his reputation. The Chapter Library copy is a 1676 edition which incorporates his historical description and maps of Great Britain, The Theatre of the empire of Great-Britain with a later work perhaps started by Speed, A prospect of the most famous parts of the World. The edition was published by Thomas Basset at the George in Fleet-street, and Richard Chiswel at the Rose and Crown in St. Paul's Church-yard MDCLXXVI and is a popular re-print, augmented, revised and re-set several times from the original 1611/12 edition. Many surviving copies are hand-coloured (see examples at raremaps.com) but this edition is monochrome. It has been rebound and re- backed and, according to the library catalogue, the order of books is now incorrect. Library volunteers can testify to this as we strive to find any overall logic of its contents when a visitor requests to see a particular map! There are missing pages, including the 1676 title page and some maps and text pages have disappeared or are damaged. However, despite the wear and tear, this is a stunning volume with beautifully engraved maps embellished with insets, town plans, coats of arms and other illustrations.

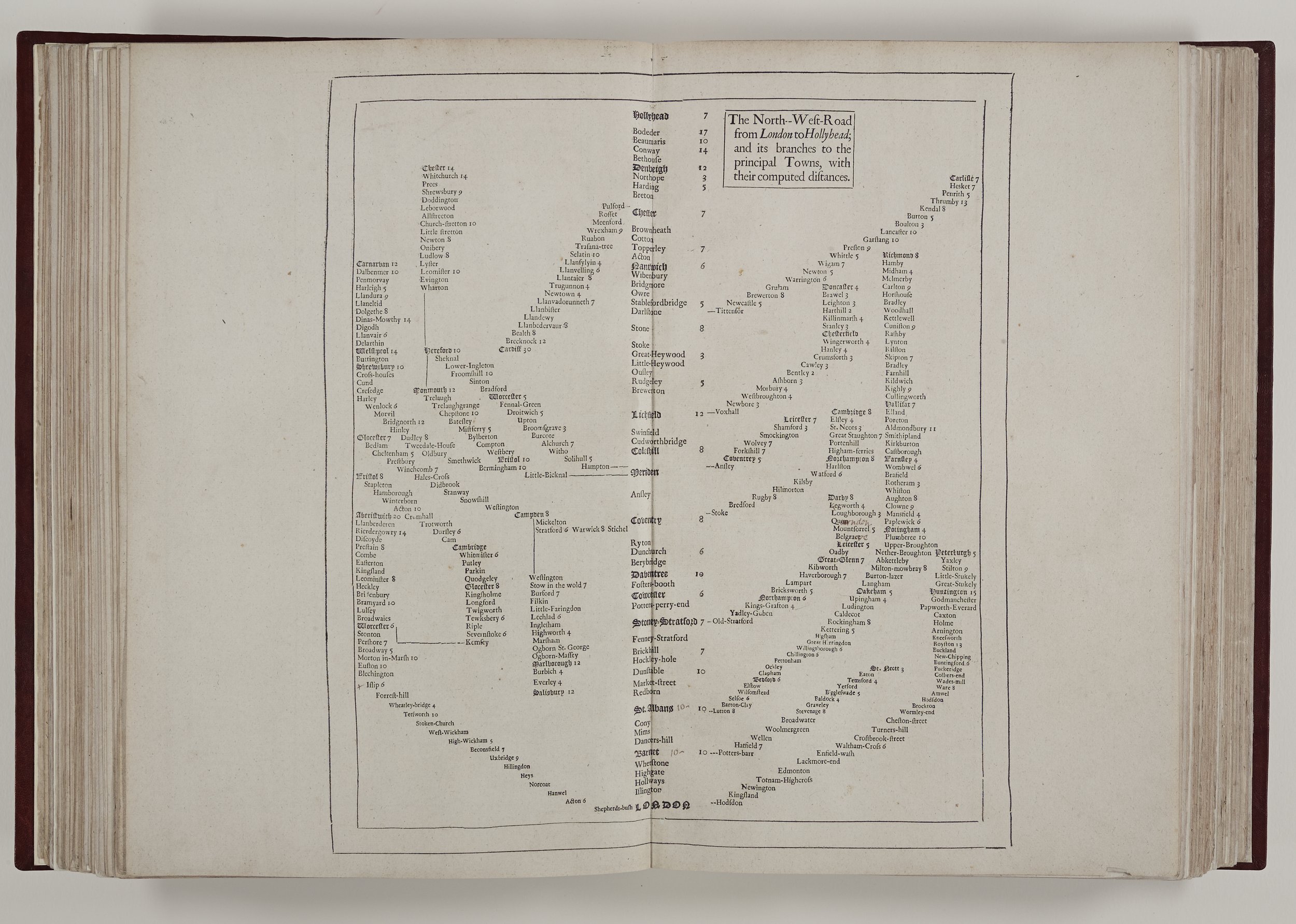

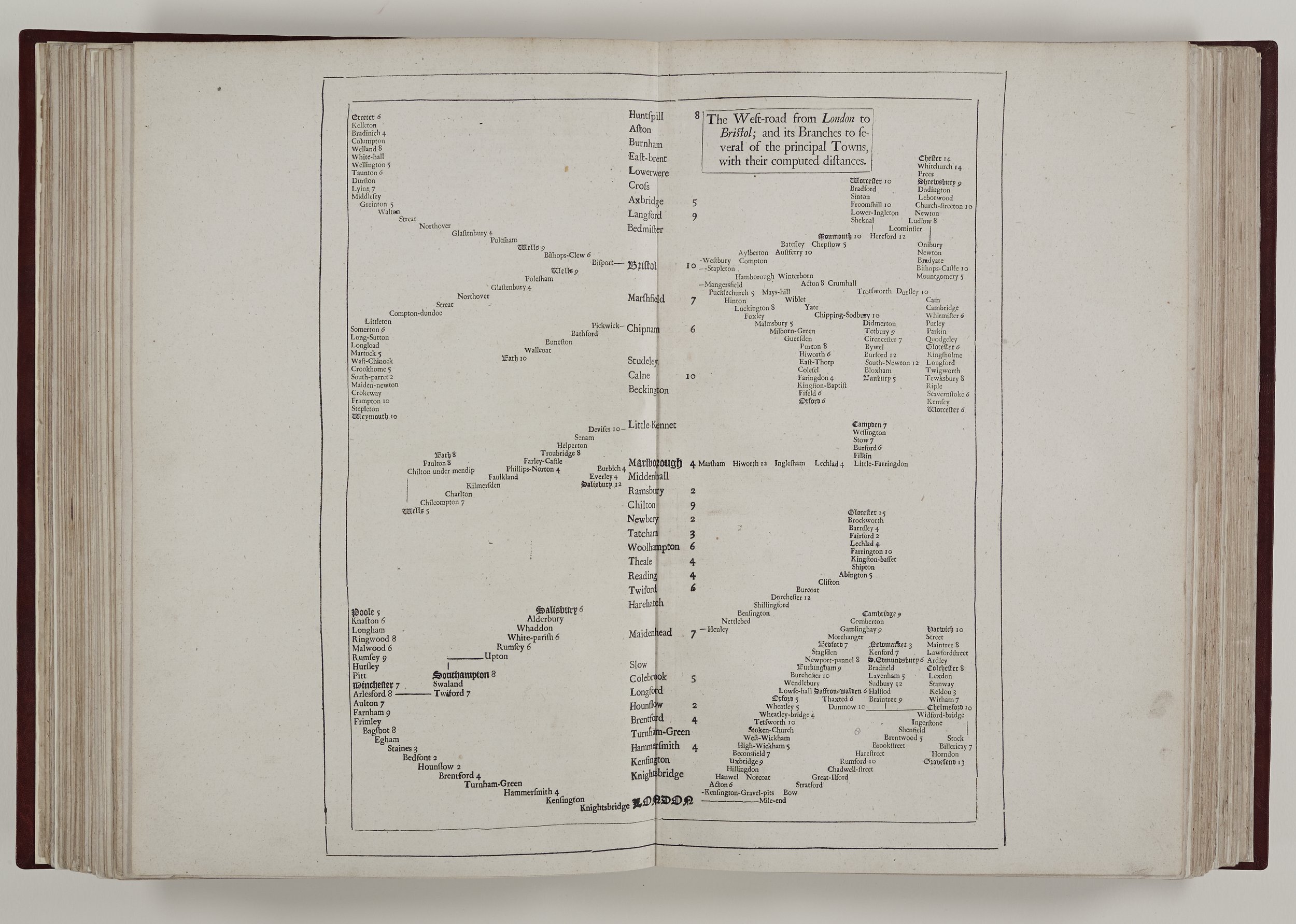

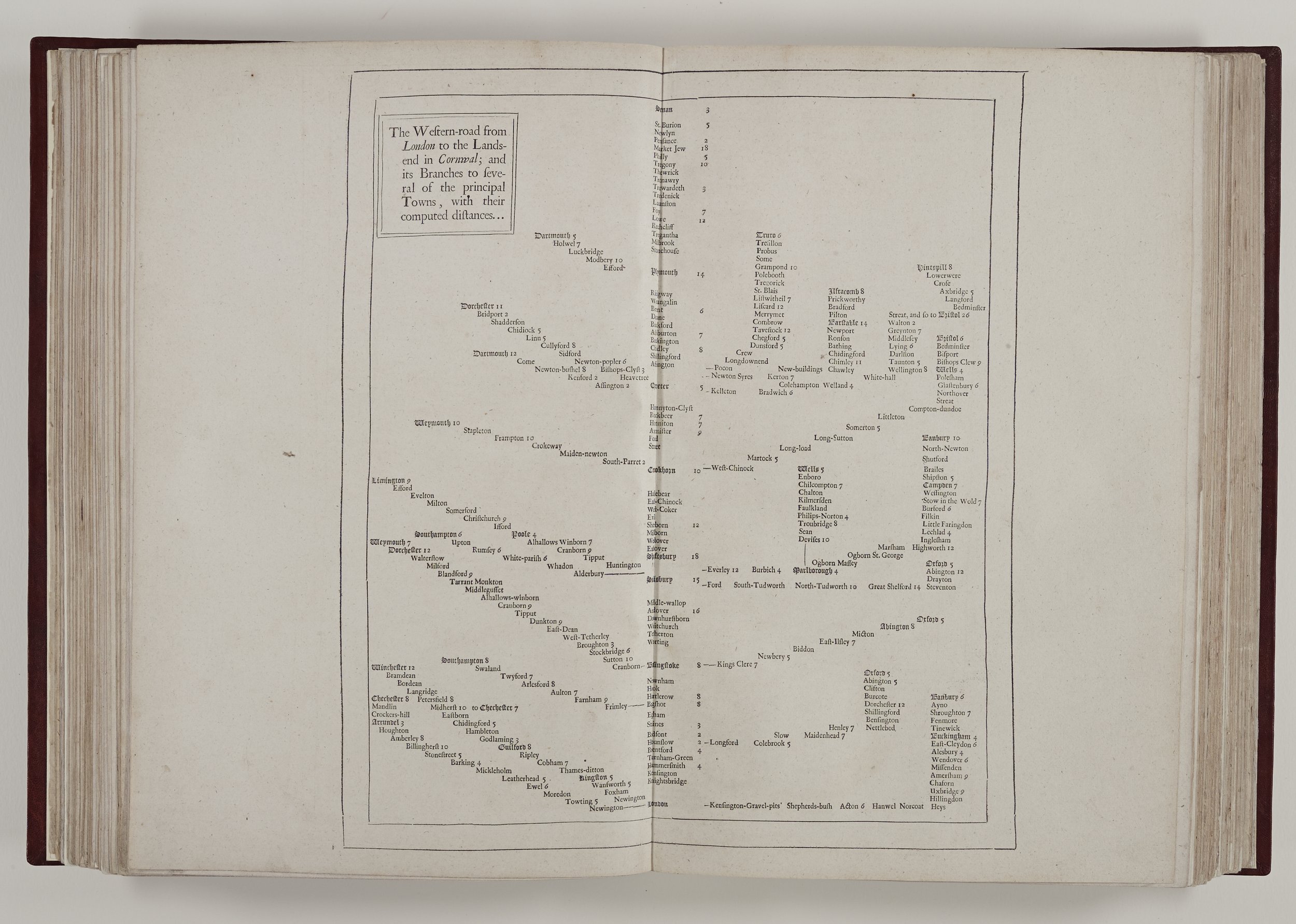

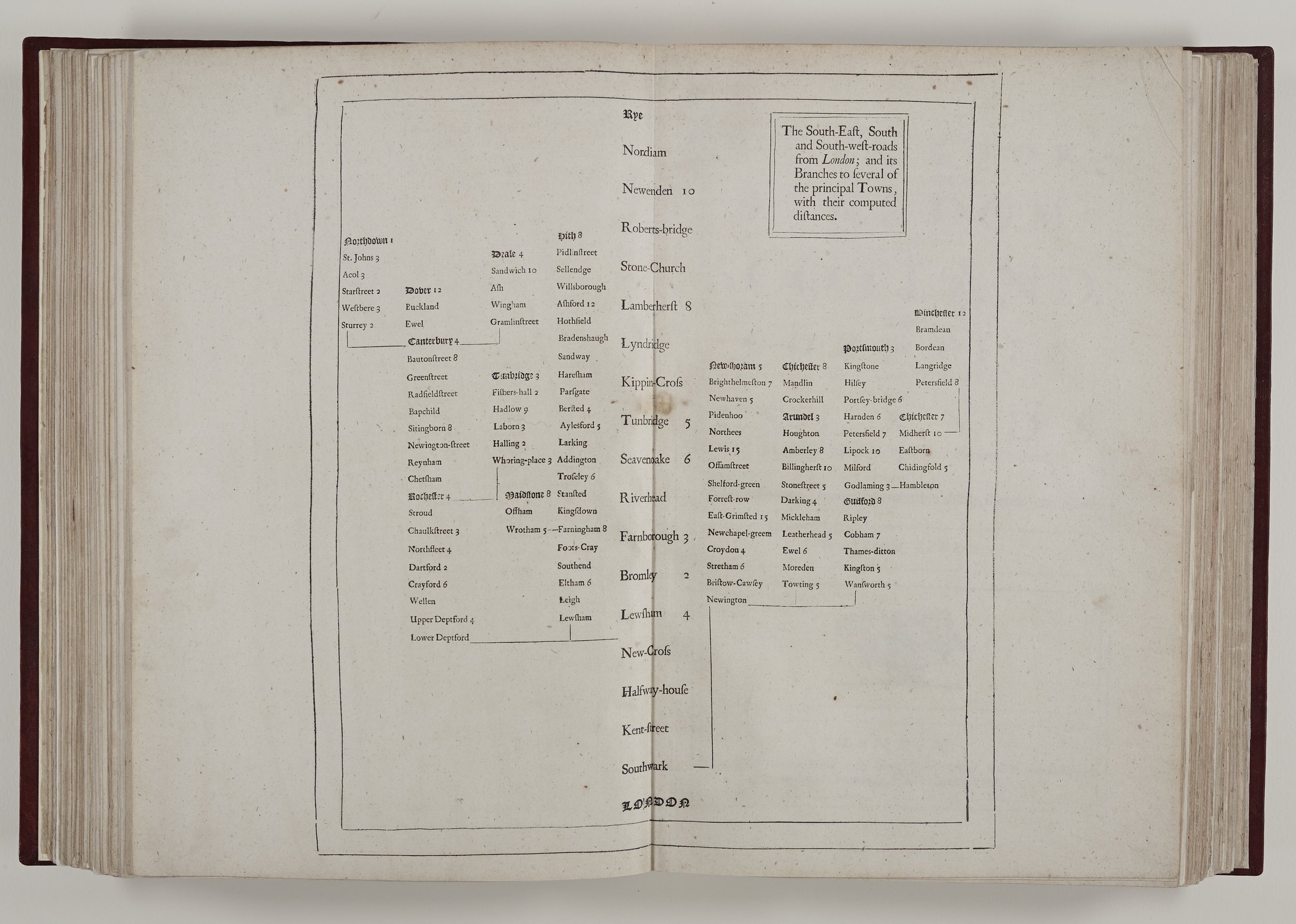

The book begins with a plate illustrating the achievements of Charles II and the arms of earlier kings and on recto the title page which summarises the contents and new additions for this edition. We can see by various sub-titles that maps have been augmented and new sections included. One such is The Principal Roads, and their Branches leading to the Cities and Chief Towns in England and Wales; with their computed distances. In a new and accurate method.

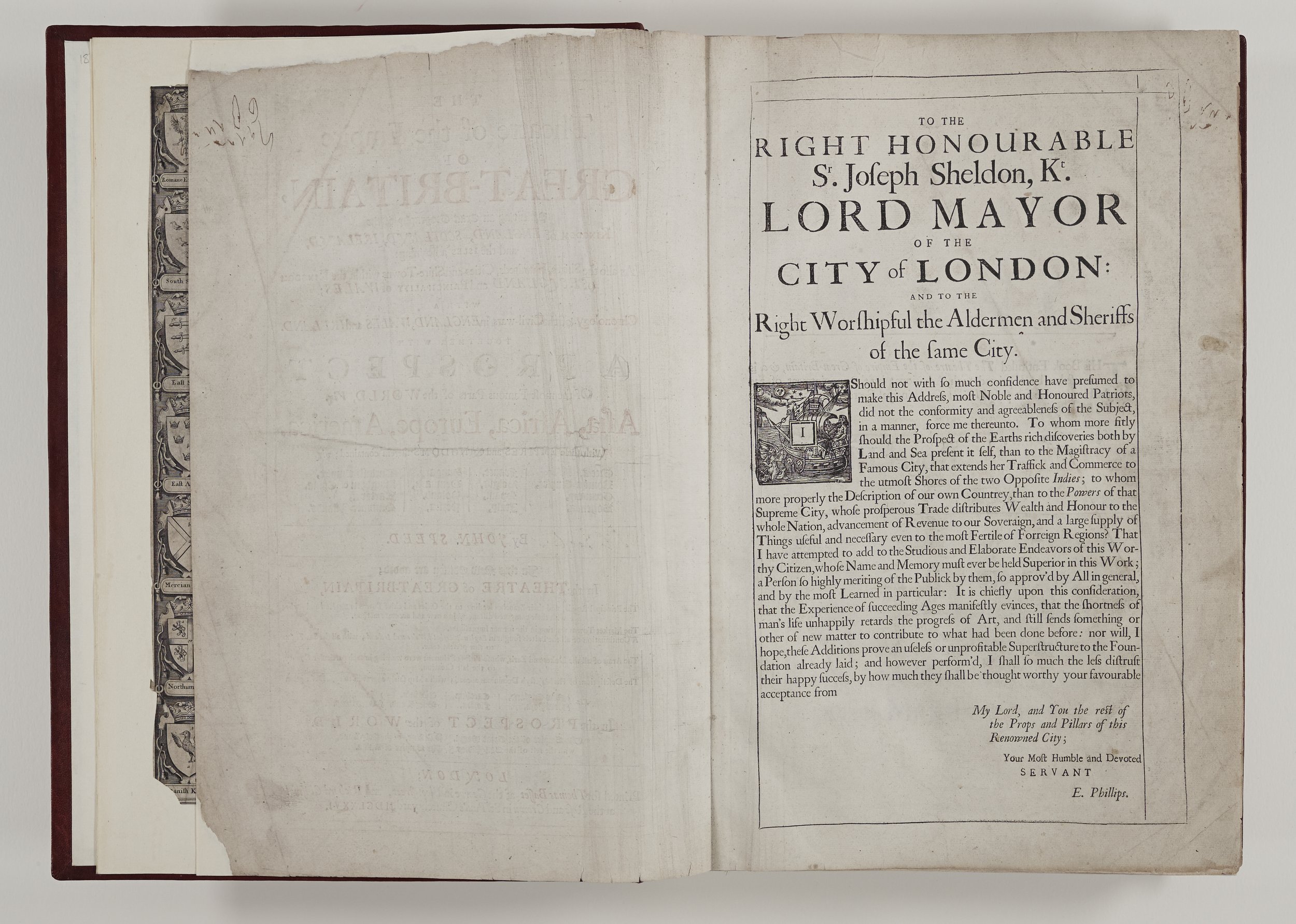

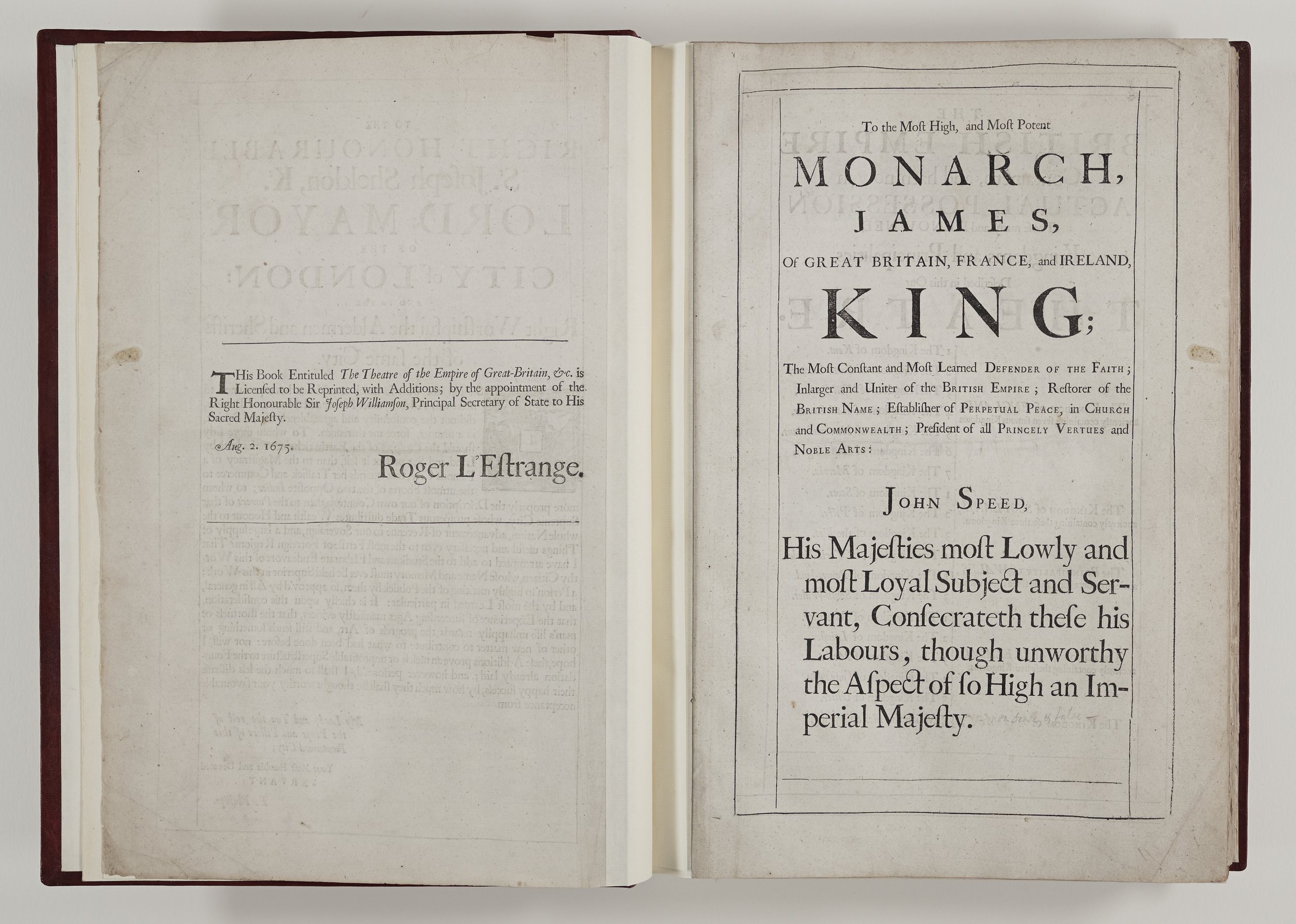

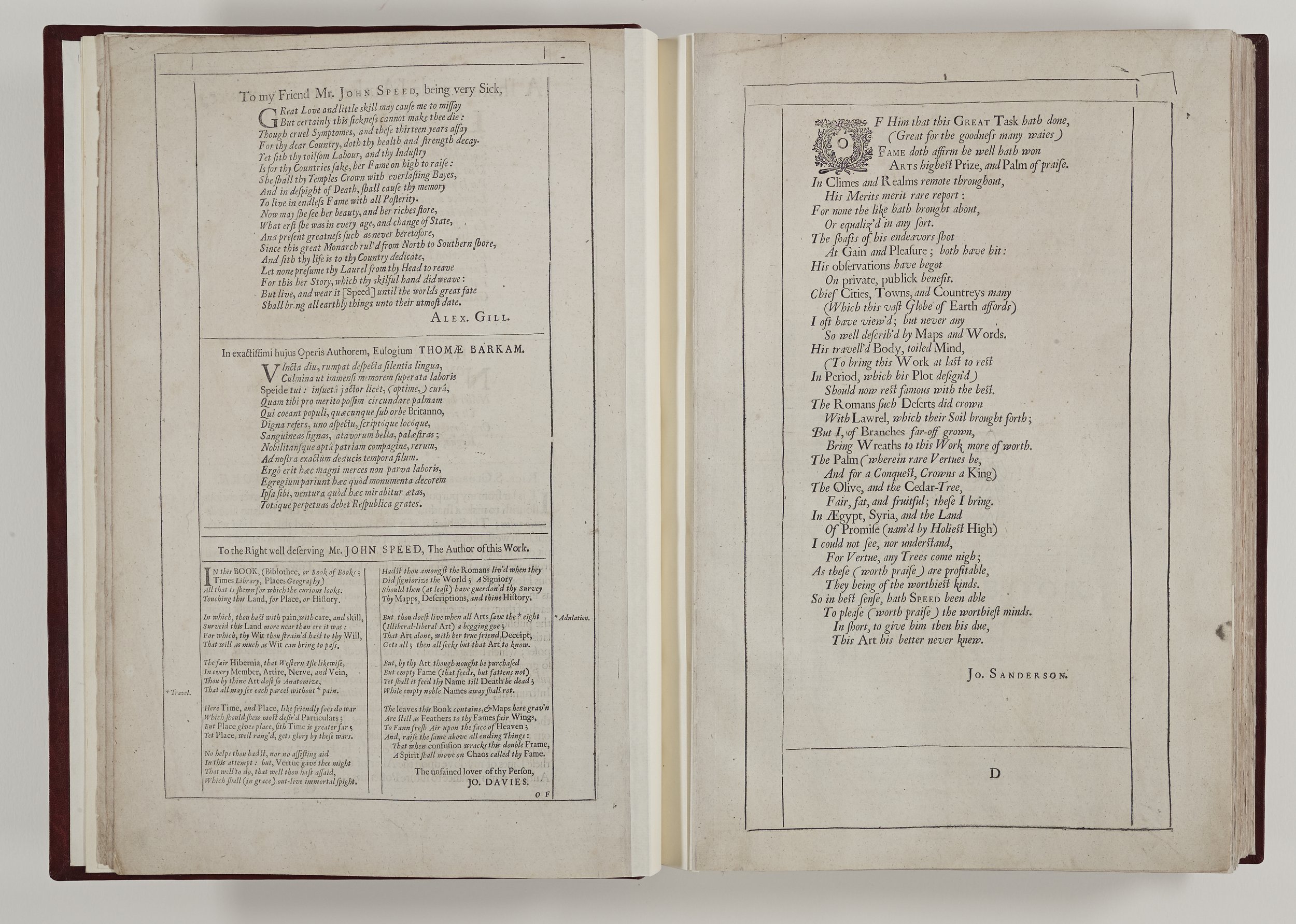

In this era it was expected that a worthy tome should be prefaced by eulogies to the monarch and dignitaries, and so next there is a dedication to the Lord Mayor of the City of London in 1676, Sir Joseph Sheldon, and the original 1611/12 dedication to James I.

Opposite the latter, on verso we see that this volume has been granted a licence for reprinting by the Principal Secretary of State, Sir Joseph Williamson (1633 – 1701), later MP for Rochester from 1690 – 1701. Williamson was a tireless civil servant and diplomat who left money for a Rochester school to be set up in his name. He was also an investor in and administrator of the Royal African Company, a trading company set up in 1660 and led by the future King James II. This company held the monopoly of the English slave trade from Africa to the West Indies and was probably responsible for the shipment of more enslaved African women, men and children to the Americas than any other single institution during the entire period of the transatlantic slave trade. (Pettigrew 2016) Williamson also donated silverware to the Cathedral which still forms some of the finest items in the collections today. The other required permission was granted by Roger L’Estrange, Surveyor of the Press, known for his translation of Aesop’s Fables.

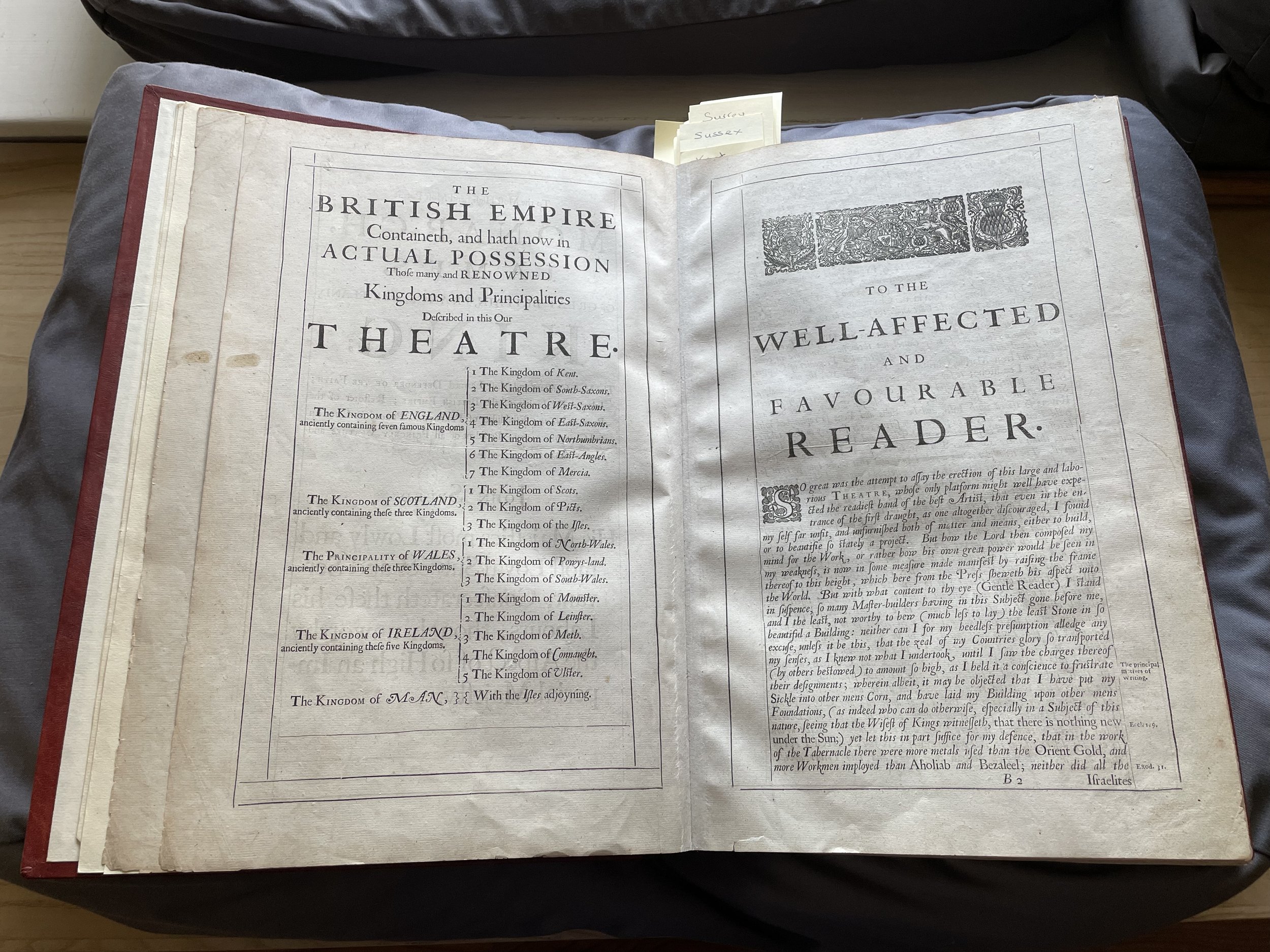

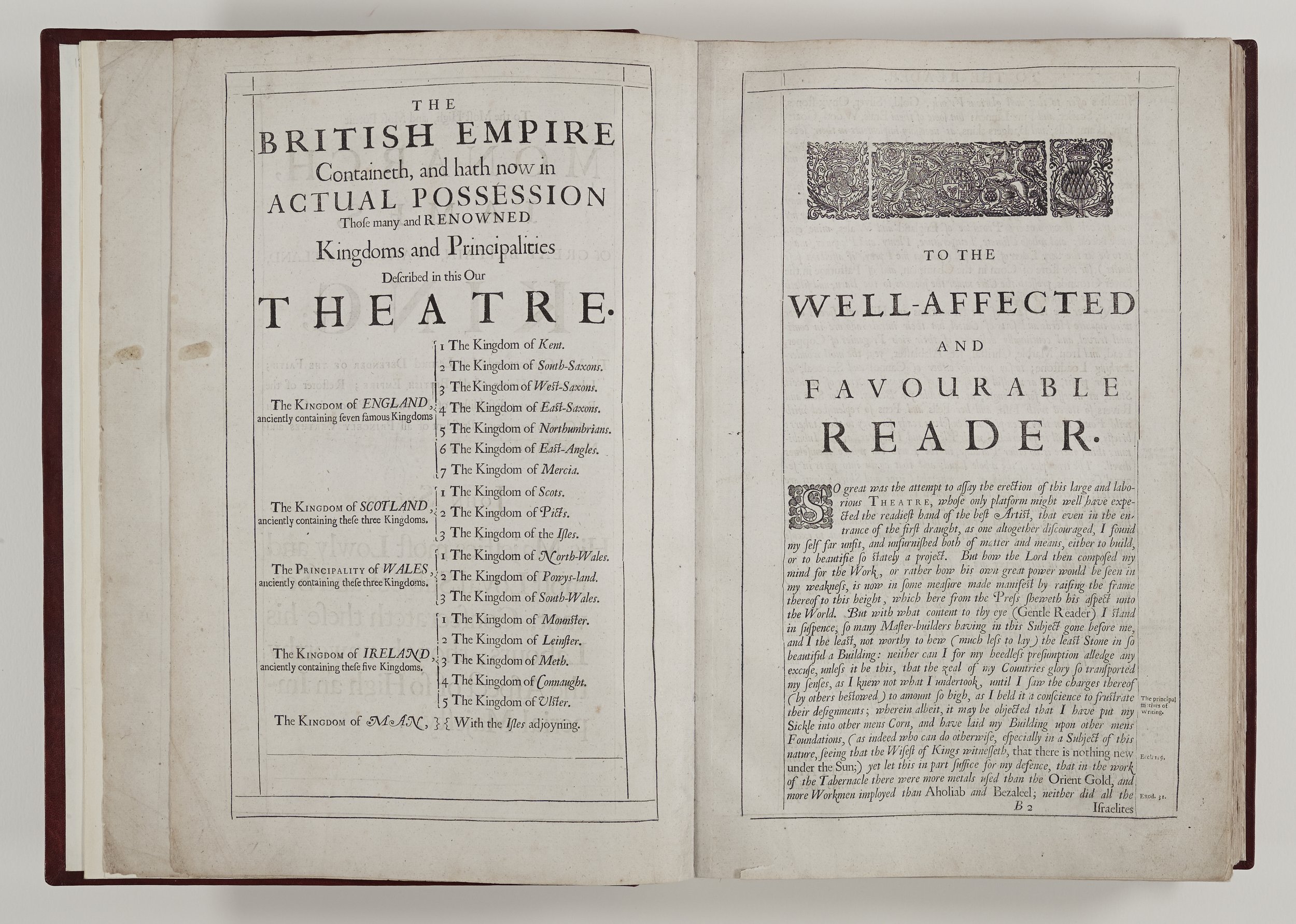

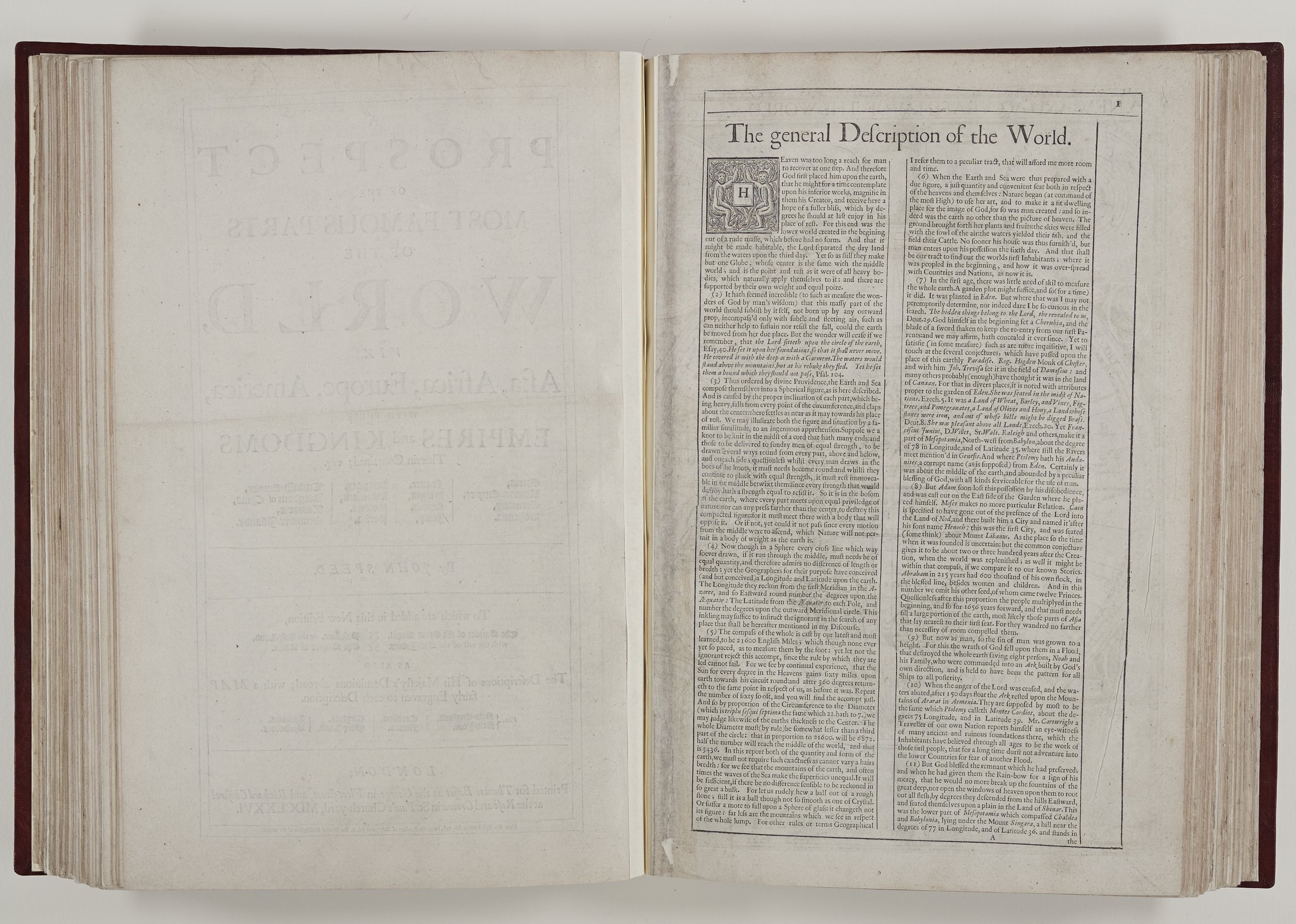

Following a list of the areas of a very local British Empire there is a wonderful address to the reader by John Speed where we first hear his voice.

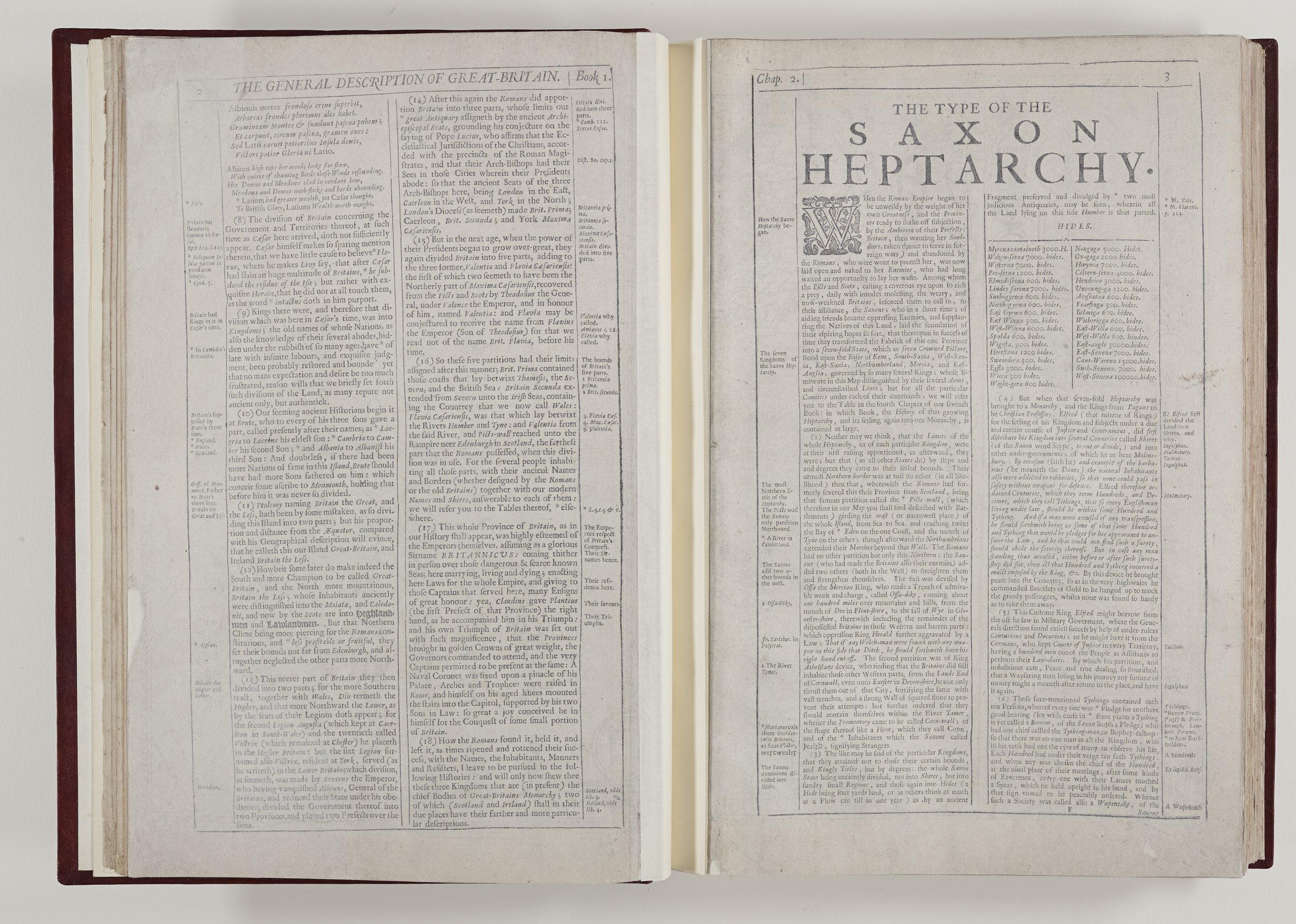

The modern reader must delve beneath the rather saccharine tone of Speed’s plea to understand his intentions. This was expected of any author but what does come through is a style which can be recognised throughout The Theatre. Speed acknowledges the work of others who have gone before him. He says “I have put my Sickle into other mens Corn and laid my Building upon other mens foundations.” It is important to note there are particular, contemporaneous English cartographers whose work Speed uses in this volume, such as Christopher Caxton (1540 – 1610} and John Norden, (1546 – 1625) and our author is clear that he owes a debt to others when he tells us that after all ‘’there is nothing new under the sun.’ As he does throughout the Theatre, here Speed is full of praise for Britain - which is another Eden, certainly in his eyes, the Eden of Europe! His enthusiasm and patriotism shine throughout the volume - or as he writes his “zeal of my countrys glory.”

There has been much academic discussion about the full extent of Speed’s travels to complete this work but here he is clear - he travelled far and wide, devising and using his own Scale of Paces {5 feet to a pace} when completing his town plans. He lists some elements he will include with each map and assures the reader that he has worked very hard and therefore has had “small regard to the bewitching pleasures and vain enticements of this wicked world.” Nevertheless, Speed married the daughter of a freeman of the City, fathered at least twelve sons and six daughters and died a relatively wealthy man.

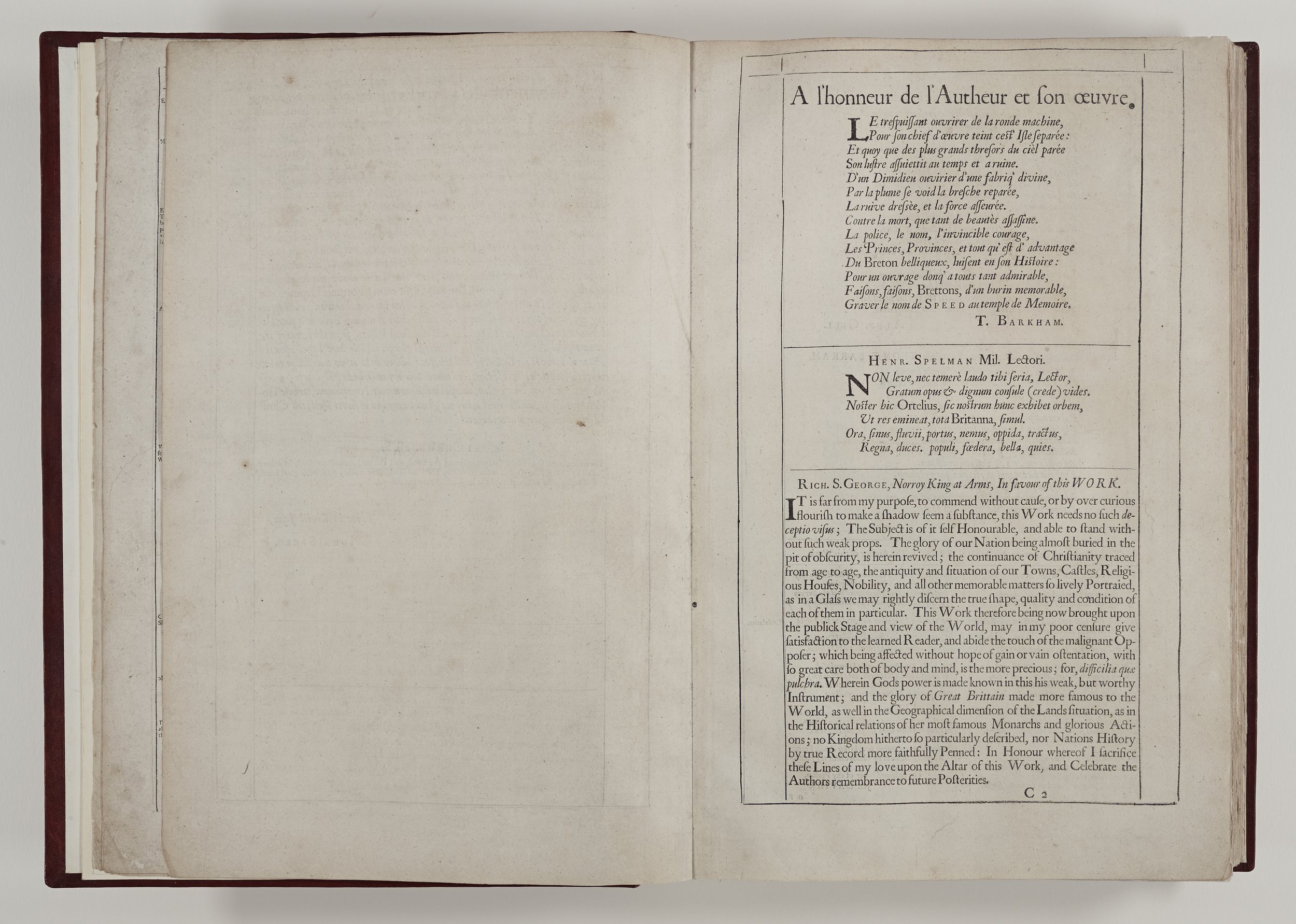

Following this are some very touching eulogies to Speed, who had died in 1629.

A contents page follows.

English counties

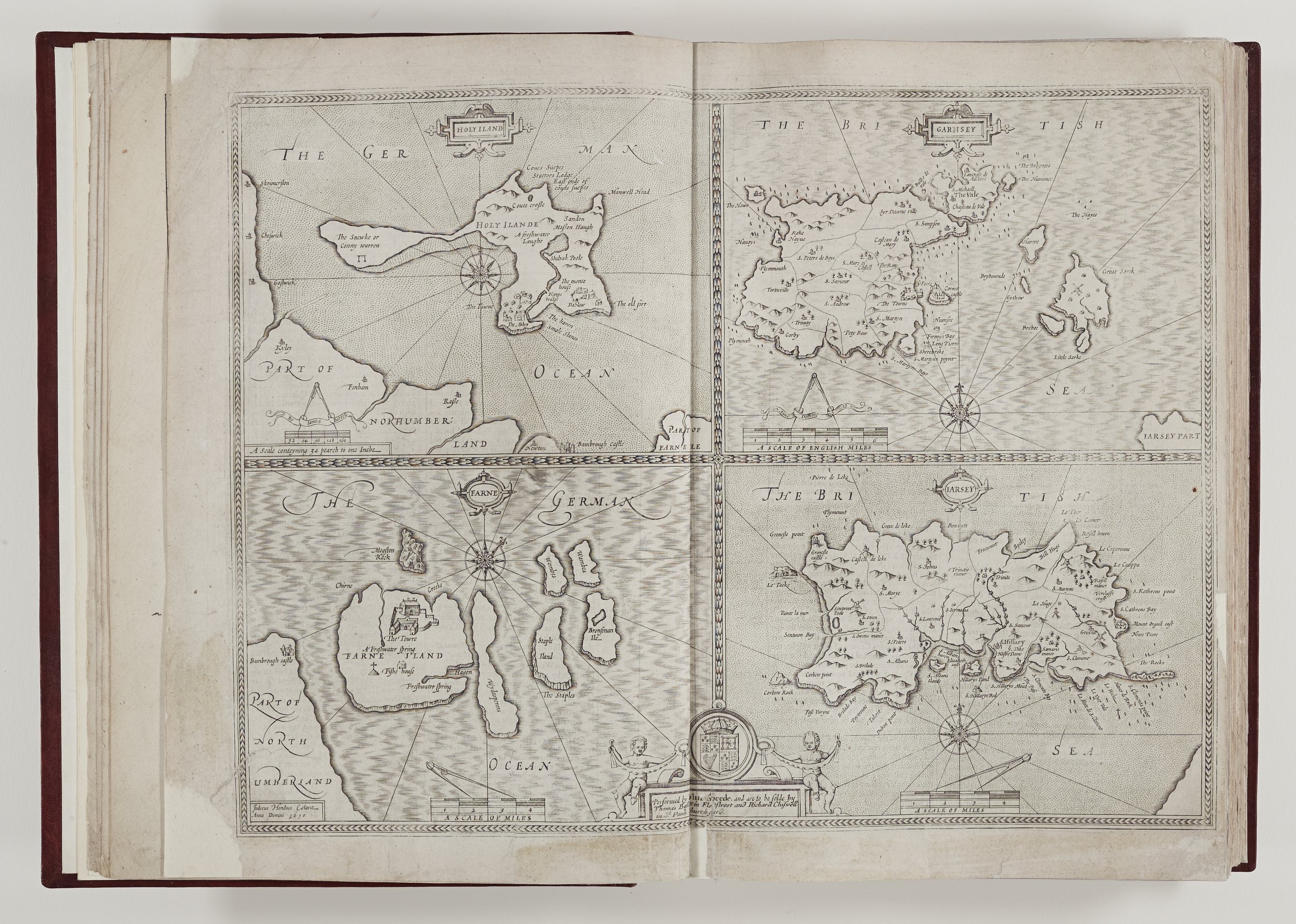

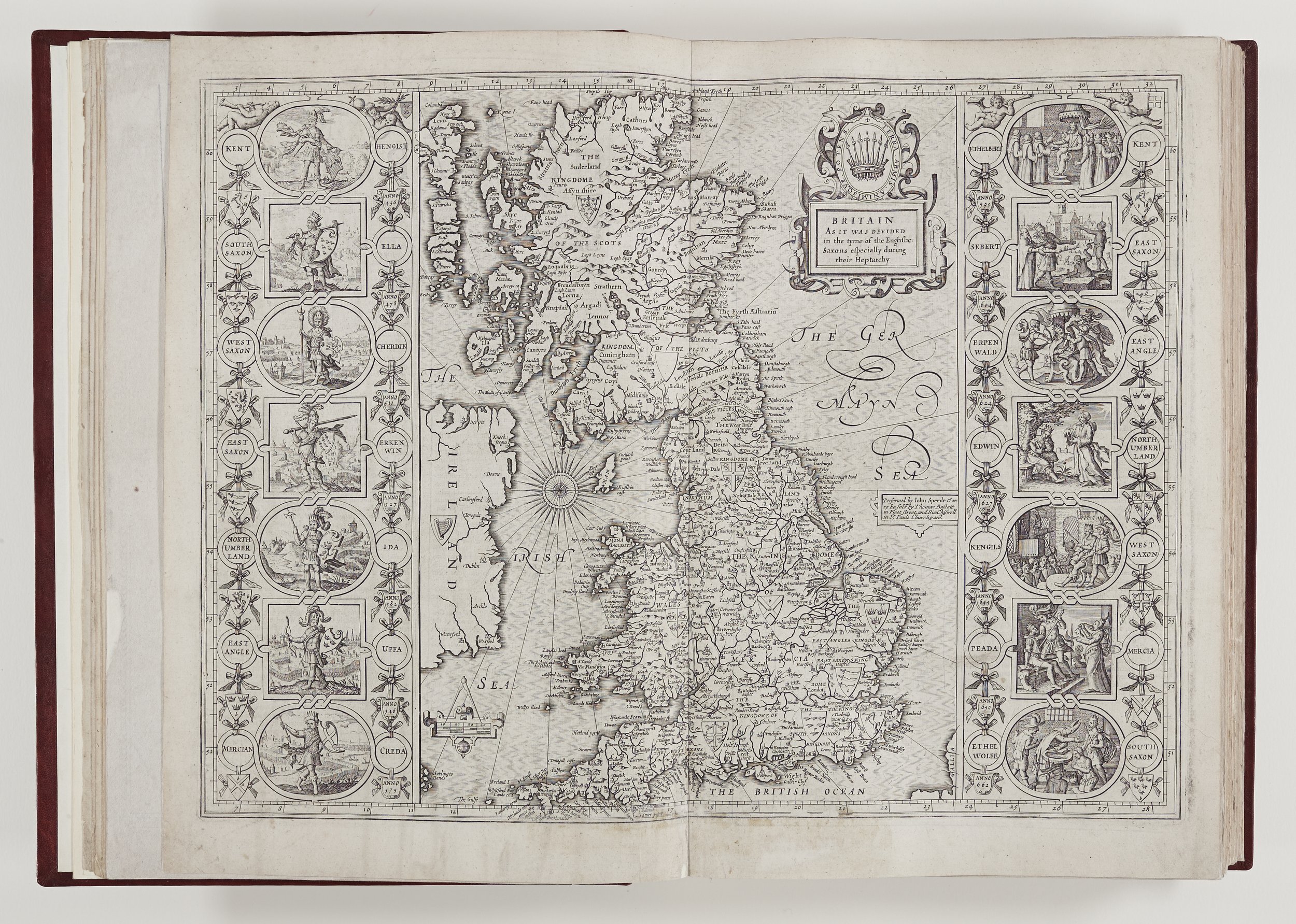

The Chapter Library copy then starts with a general description of Britain but sadly the accompanying map is missing. Instead there is a map of British islands which, oddly, appears again at the end of this volume with Speed’s description. After the Saxon Heptarchy – a description of the seven petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England there is an overview of England.

Speed researched Britain’s history and geography using the cabinets and libraries of noblemen which were made available to him; the records of Crown officials in the shires and his own travels through “every province of England.”

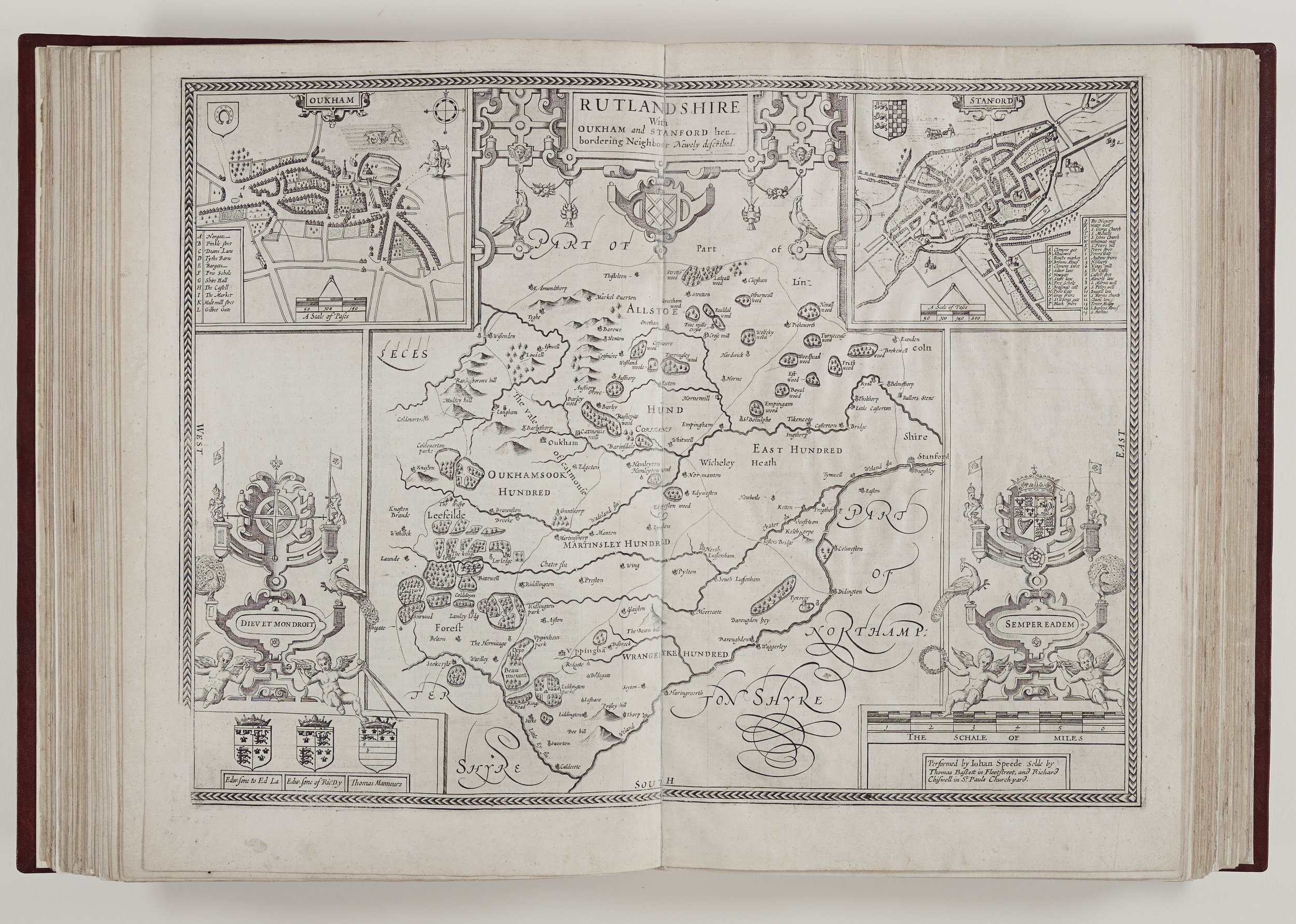

The county maps are based on the work of contemporary cartographers such as Saxton, William Smith, Norden, Sir Henry Spelman, John Harrington and others but they have Speed’s additions from his own observations and the material he compiled to elaborate the designs.

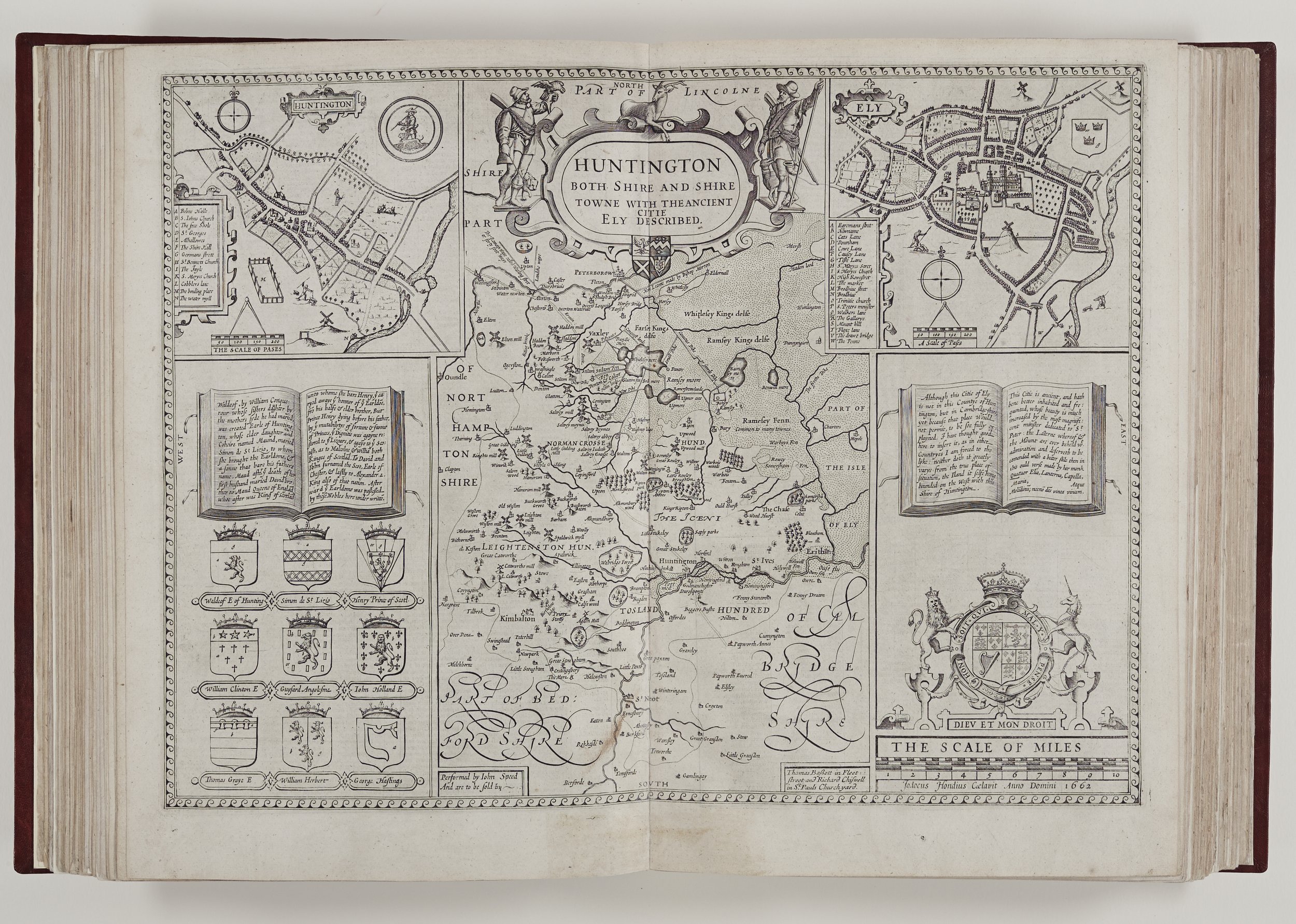

The engraving of Speed’s own county, Cheshire, was originally produced by his contemporary, William Rogers. It is conceivable that Speed might have considered Rogers for more engravings, had he not died in 1604. The principal engraver, Jodocus Hondius, who possibly completed the copperplates at least two years before the first publication, added fashionable, pictorial map borders amongst other flourishes and the result was text and maps which complement each other well.

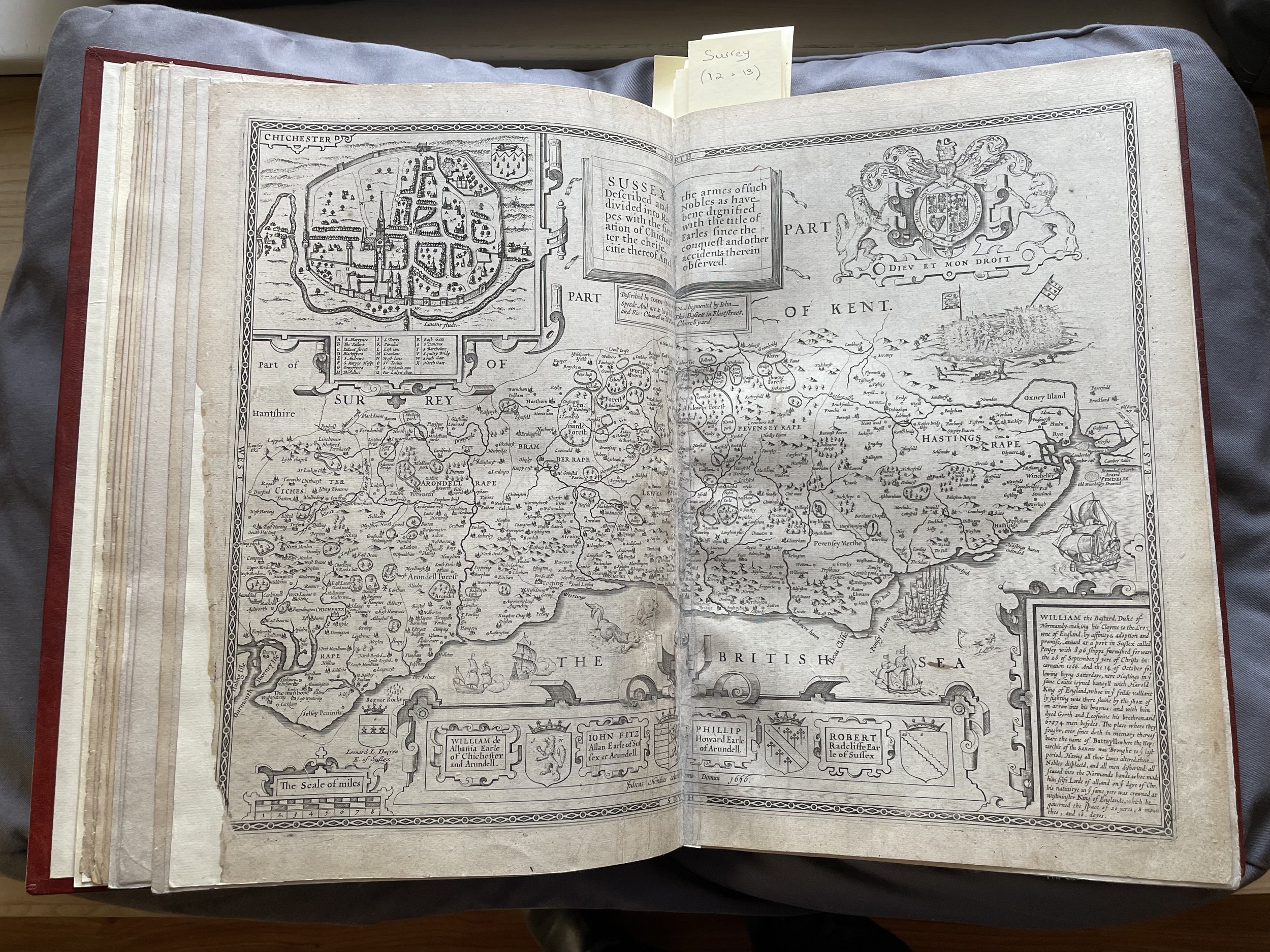

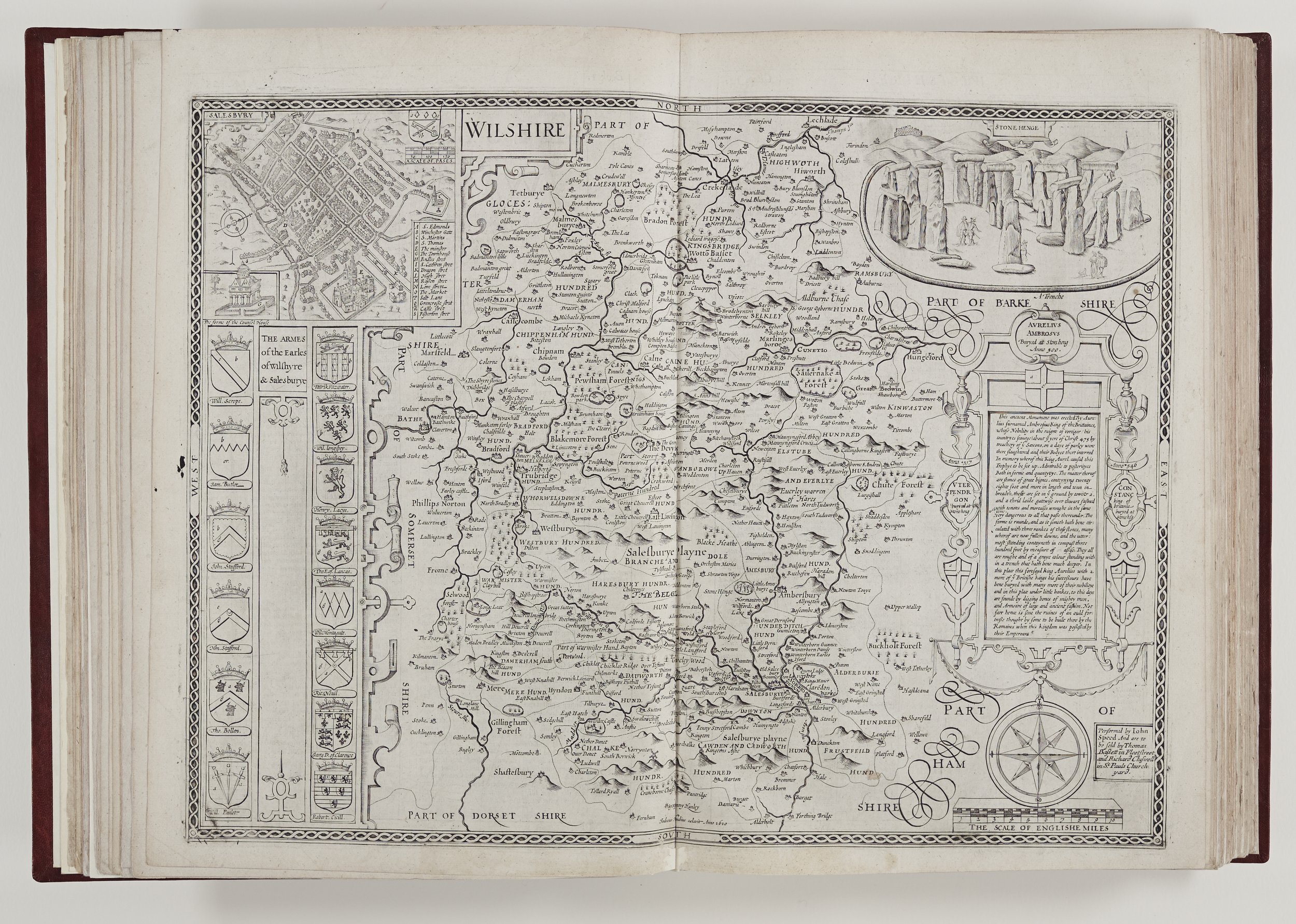

Perhaps Speed’s greatest contribution to cartography was his town plans. There is evidence that he used and revised some existing plans by William Smith, for example, but at least fifty plans can probably be attributed to Speed alone. They are a mixture of ground plans and birds-eye view perspective often with the addition of every-day features such as mills, maypoles, gallows and shambles. They show the expansion of town life beyond the necessary city walls and fortifications of previous centuries. These plans are of great importance to historians and archaeologists and have provided a basis for the reconstruction of Tudor towns. Some are particularly accurate and detailed, such as Salisbury and York where houses can be seen erected on bridges over the Rivers Ouse and Foss. In his Nottingham text, Speed uses his personal scale to give an exact distance of his circuit of the remaining medieval city walls, which he measures at 2120 paces. His use of this personal scale in many of the town plans is another indication of his diligence and first-hand knowledge.

Scale is an issue which must have given Speed cause for great deliberation. The maps had to fit the chosen size and format but the counties are neither similar in size nor regular in shape. The scale is therefore different for many counties and Speed gives distances in miles, as well as the paces he uses in towns. However this still left the problem of which mile to use. The statute of 1593 had established that eight furlongs or 1760 yards constituted a mile but this was only adopted gradually, and only nationwide after more than another century had elapsed. Many counties continued to use the greater, middle and lesser miles for many decades and Speed does not indicate a preference.

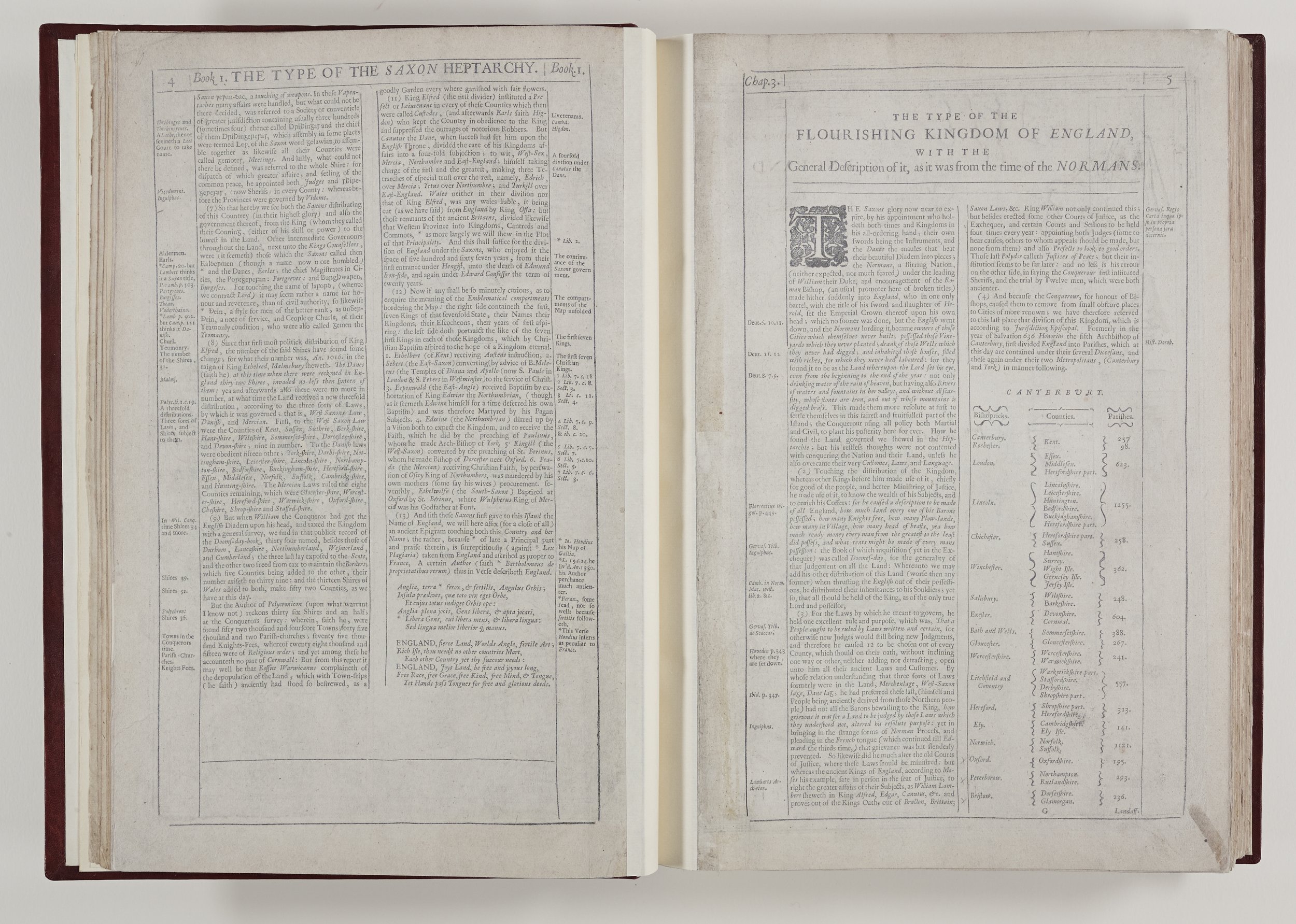

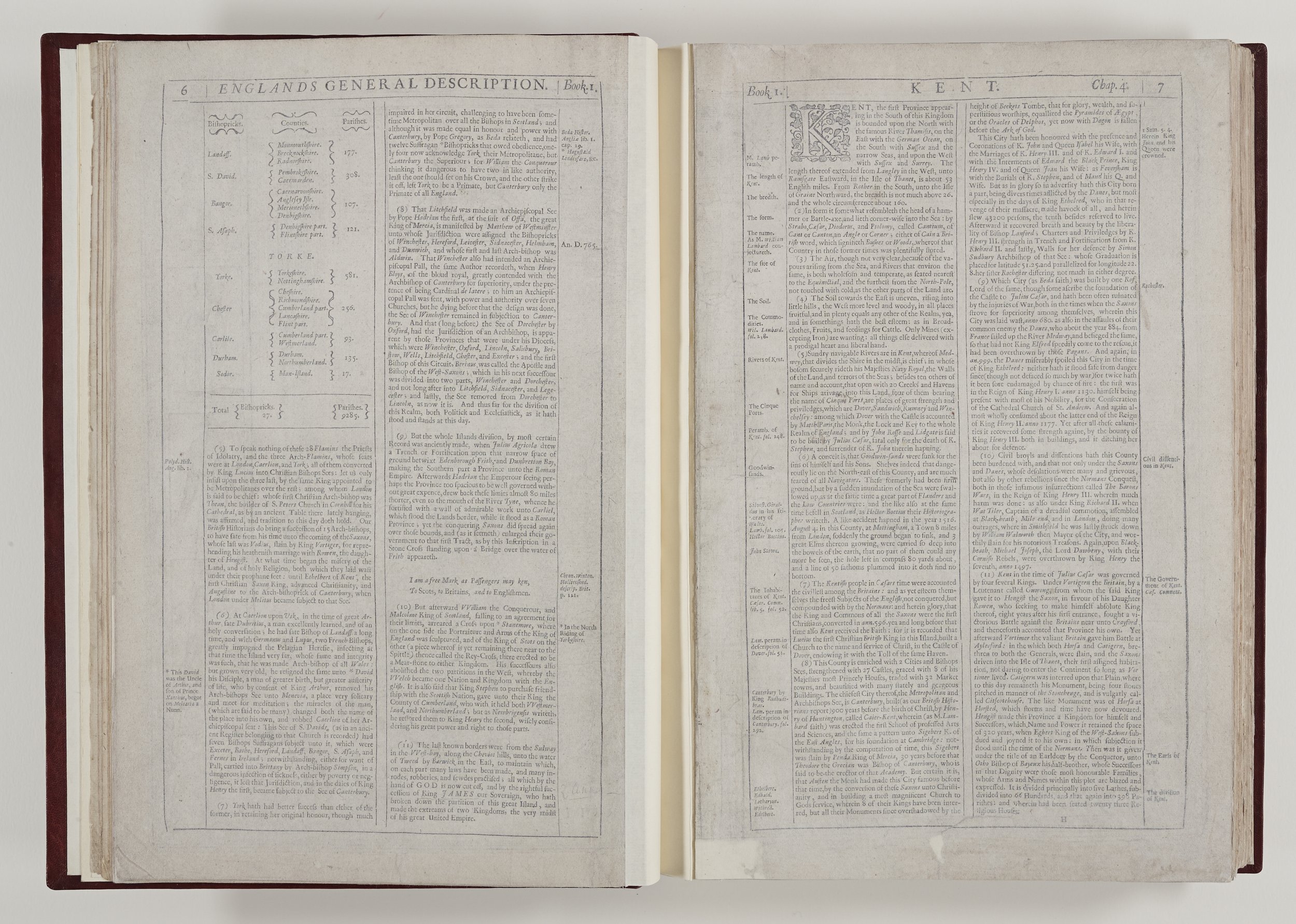

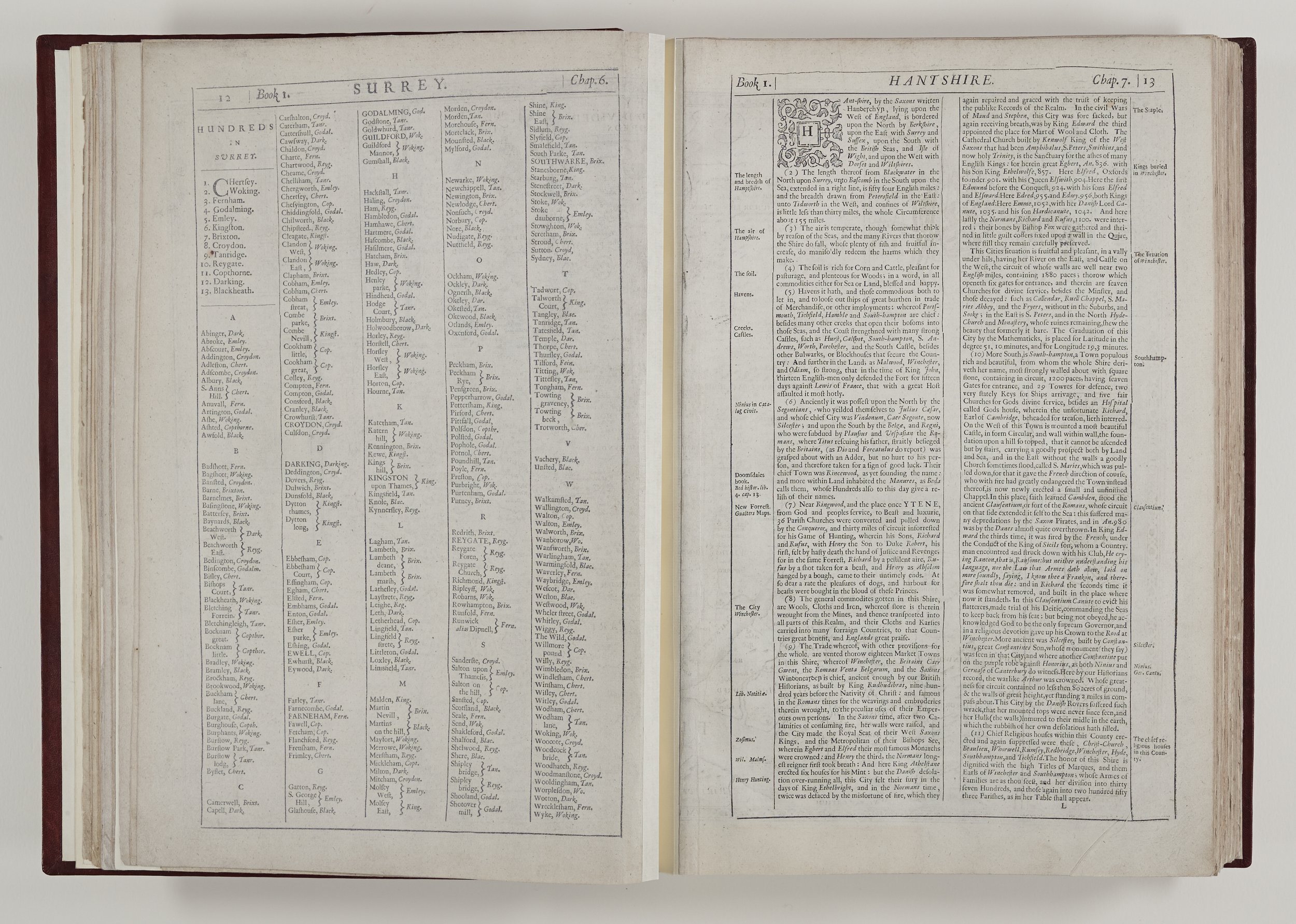

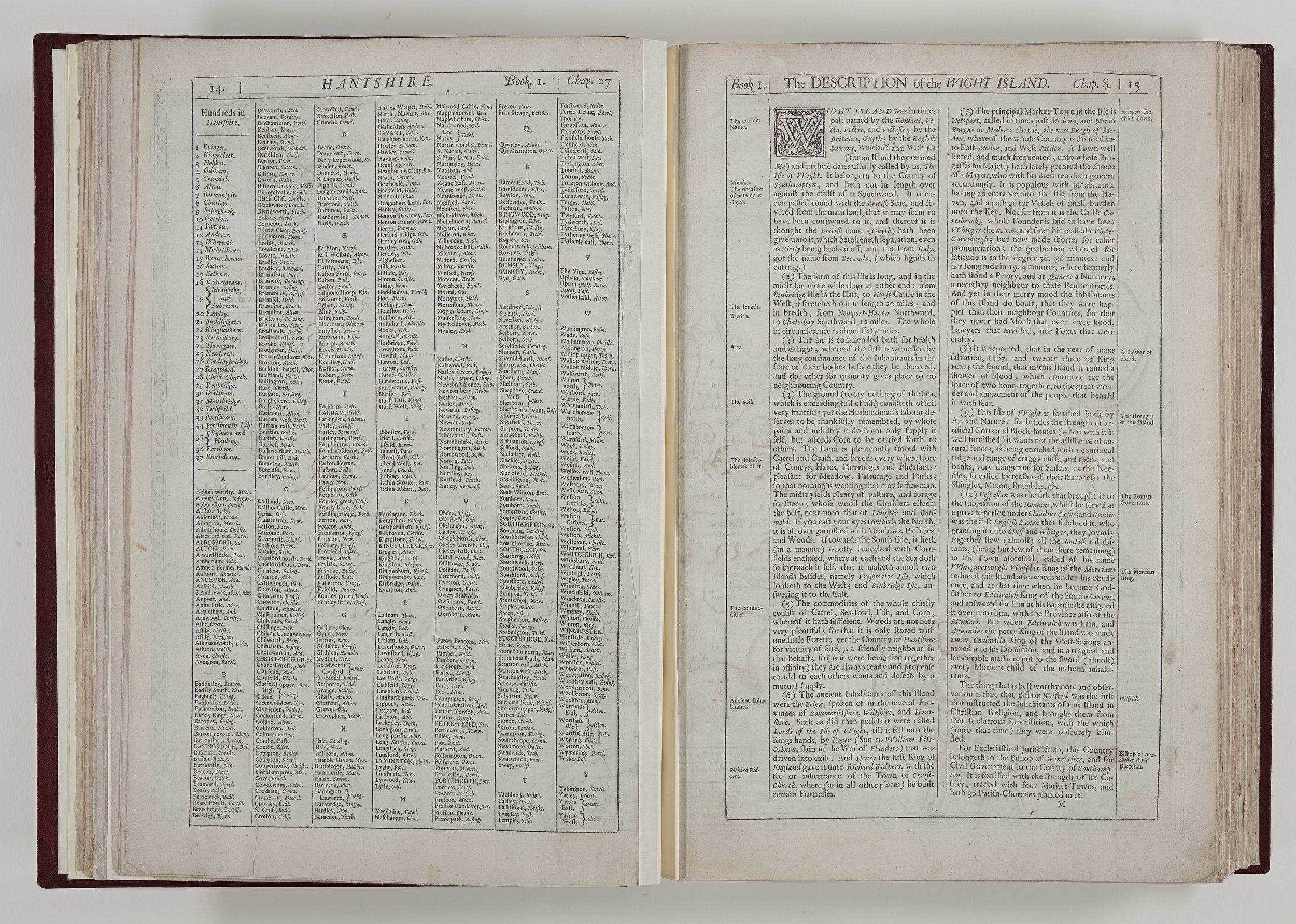

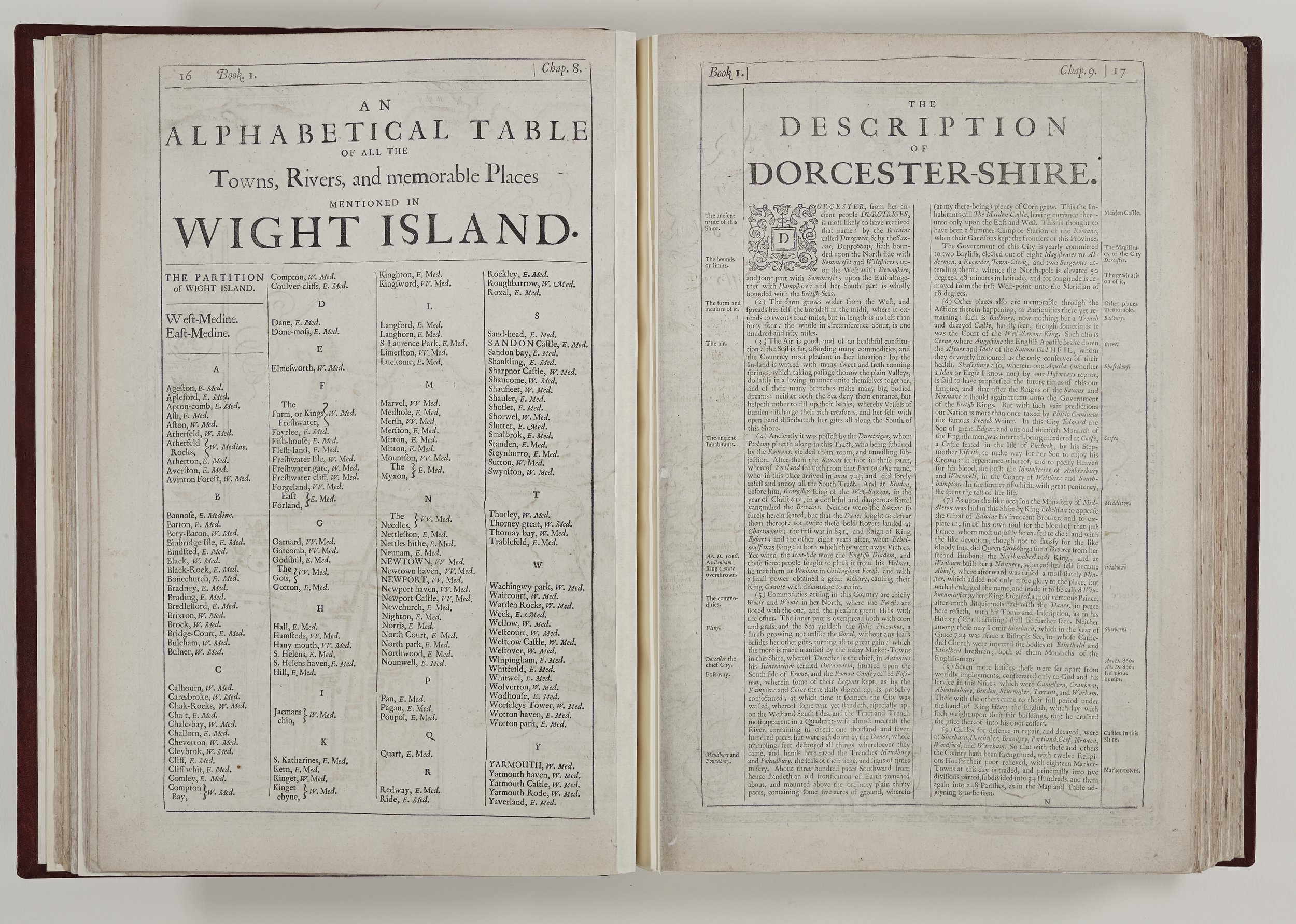

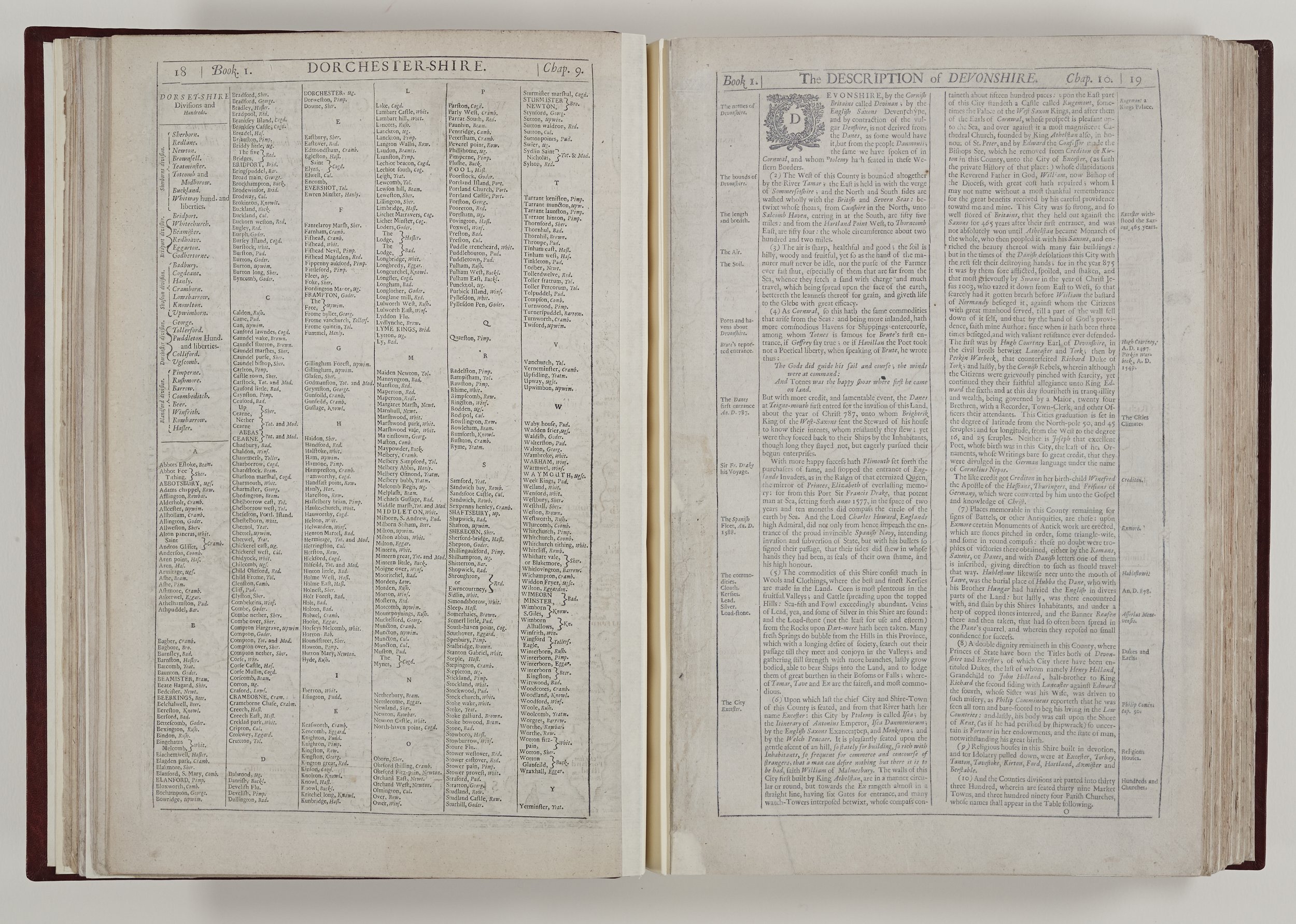

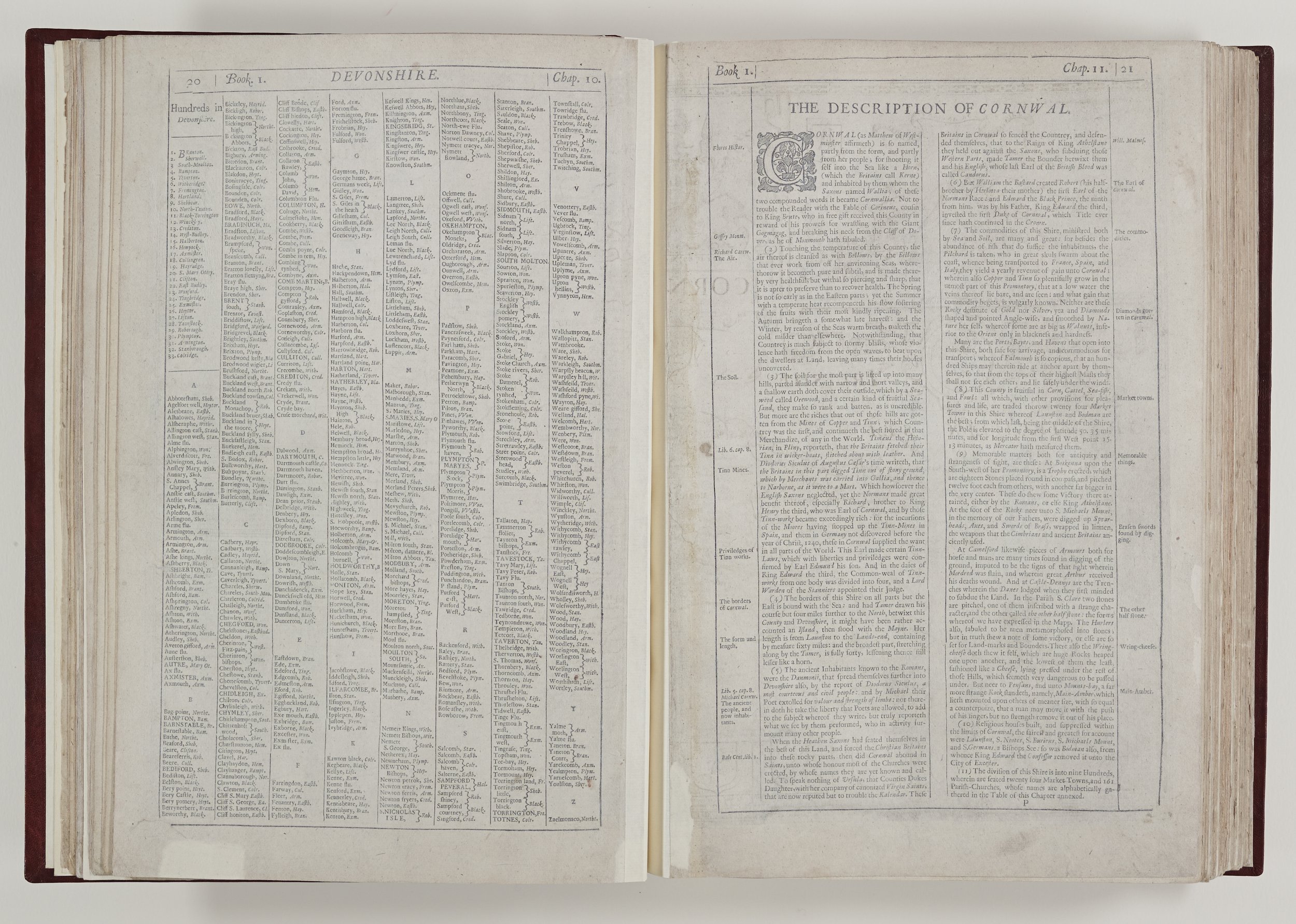

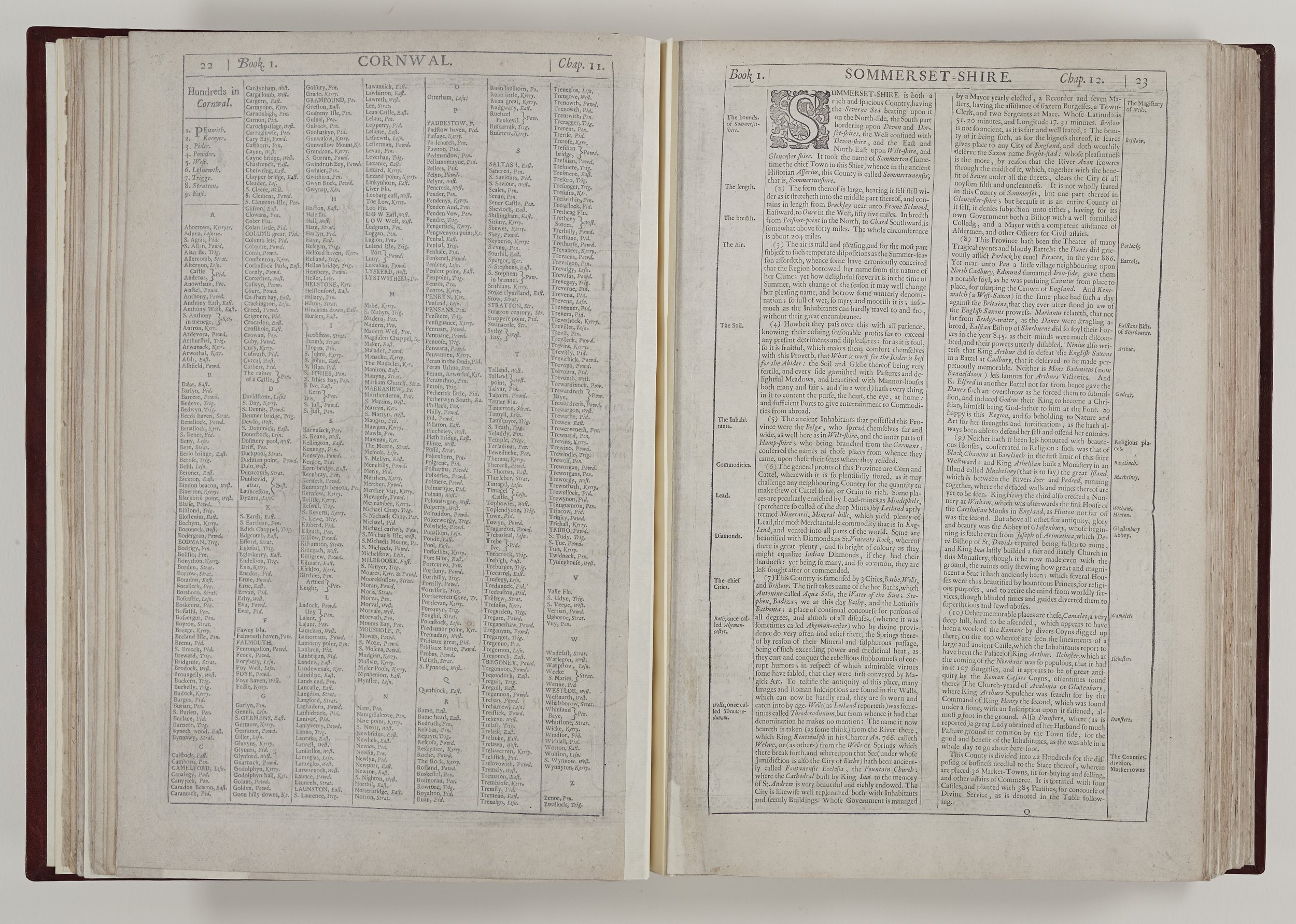

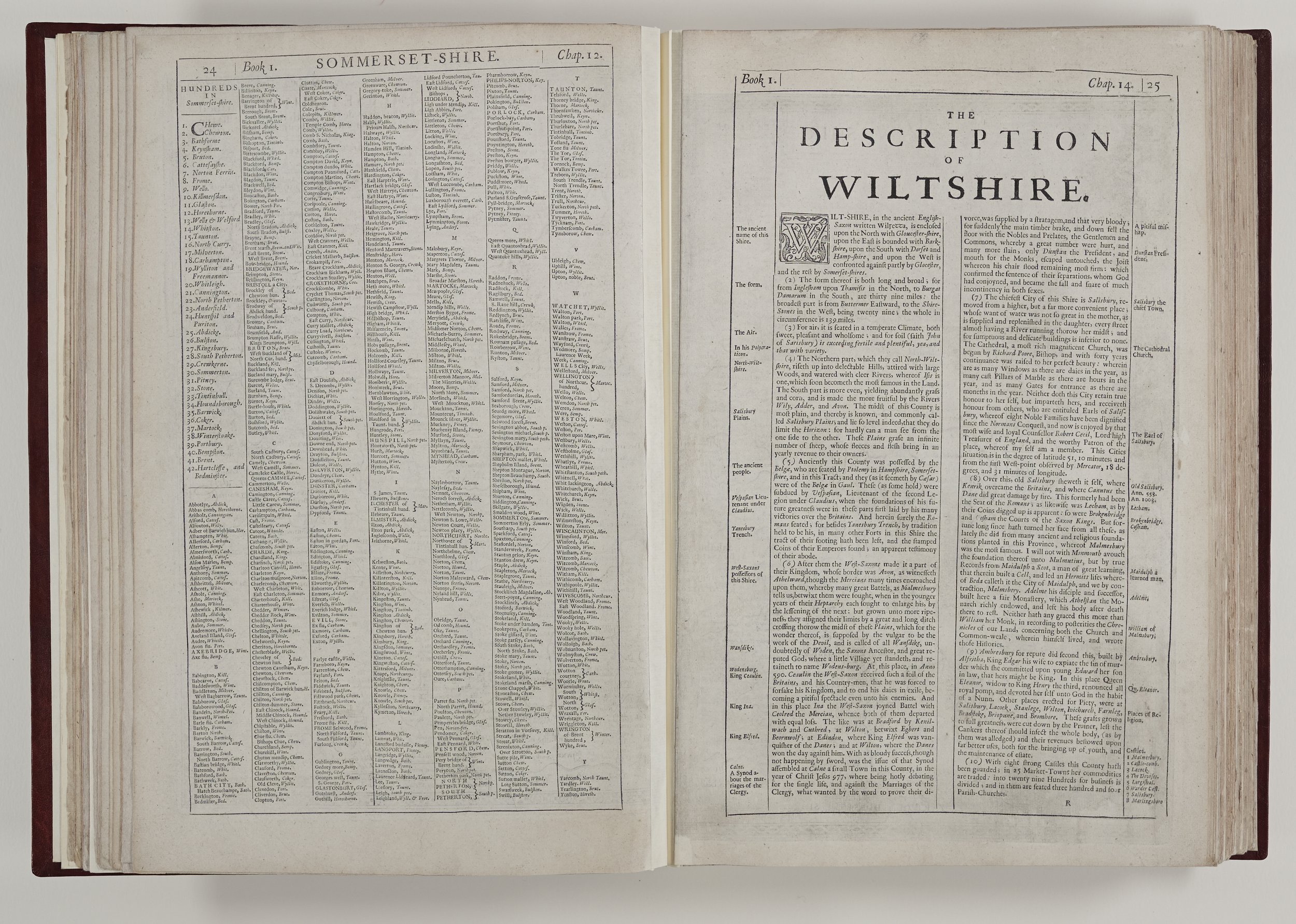

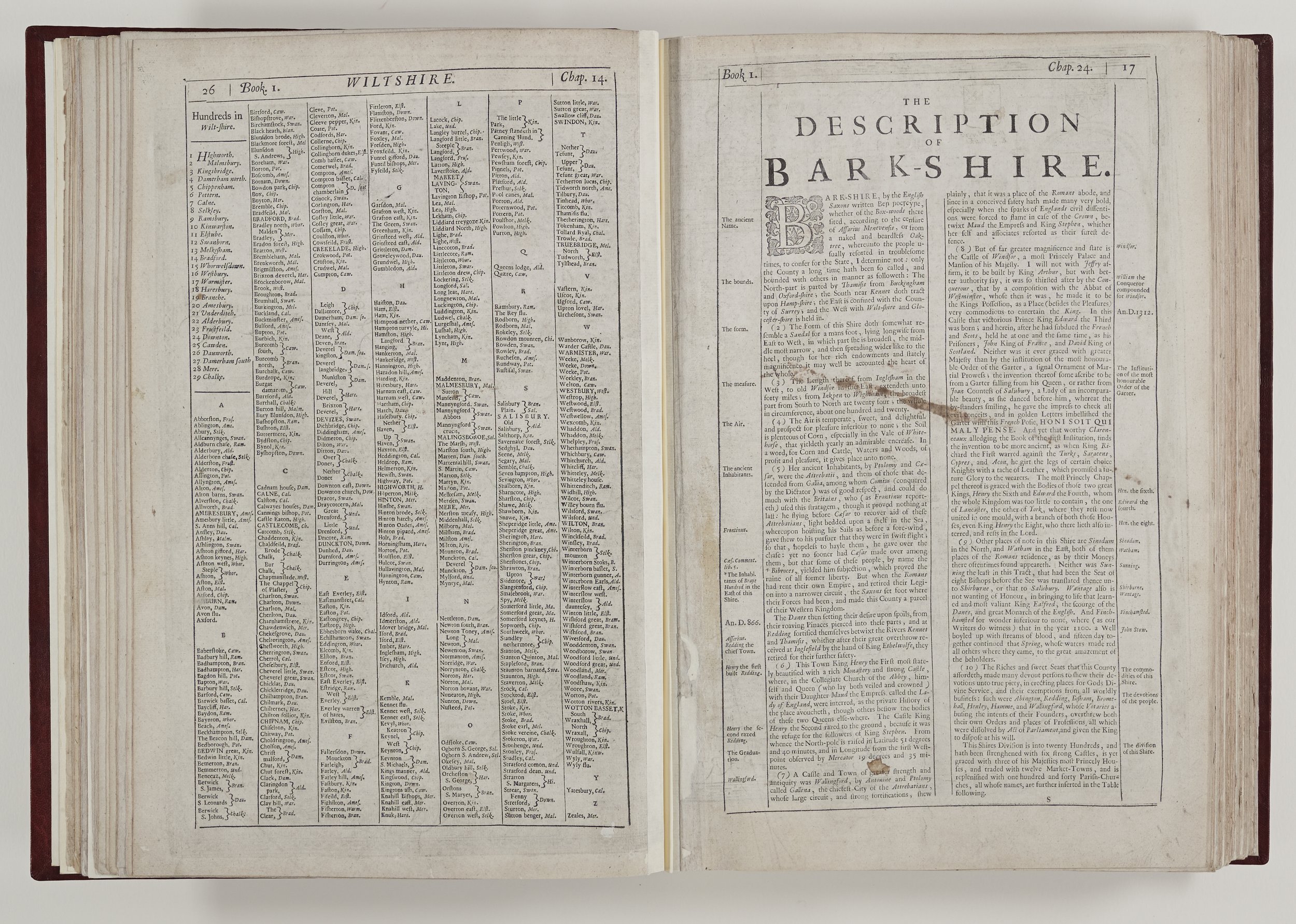

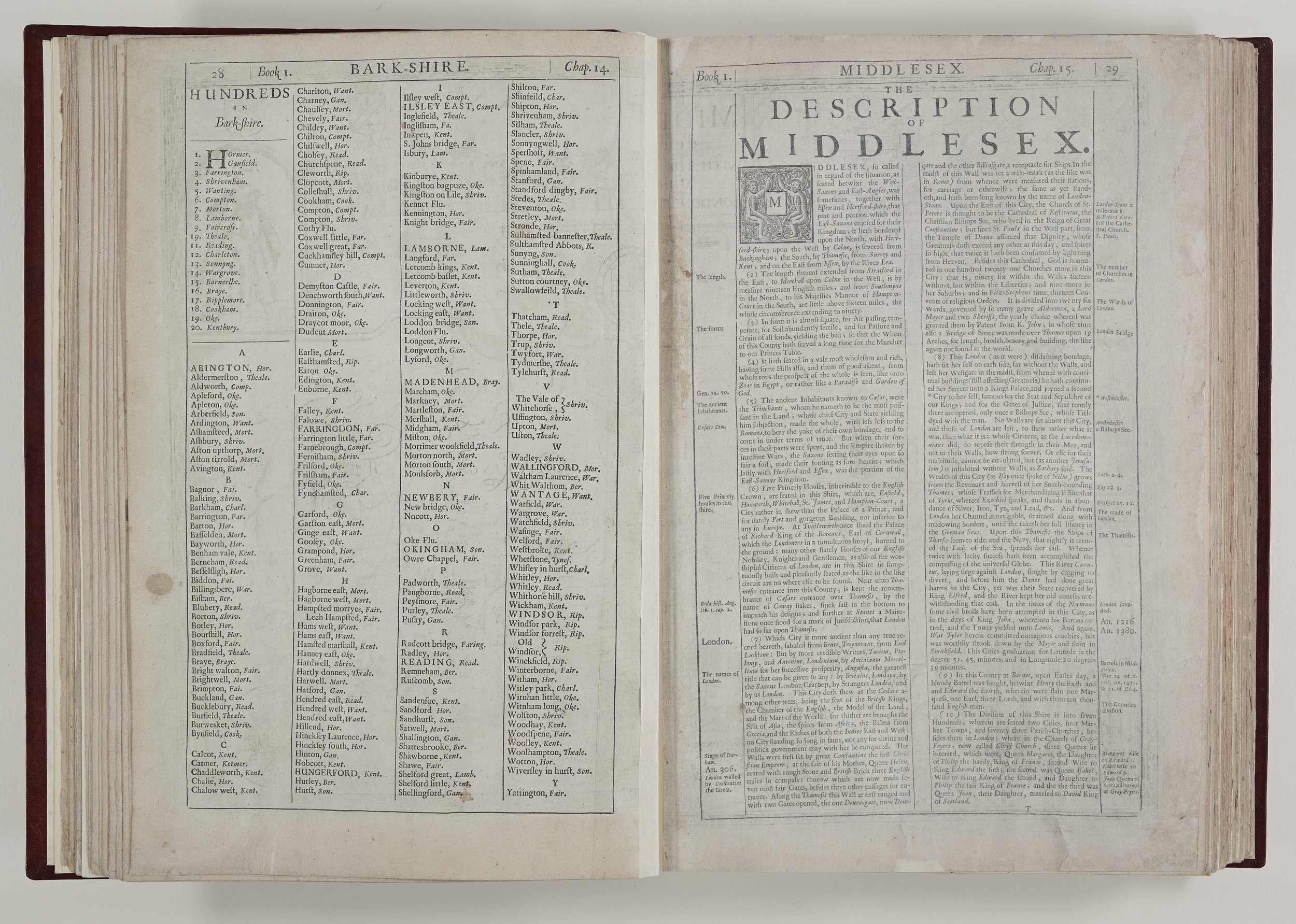

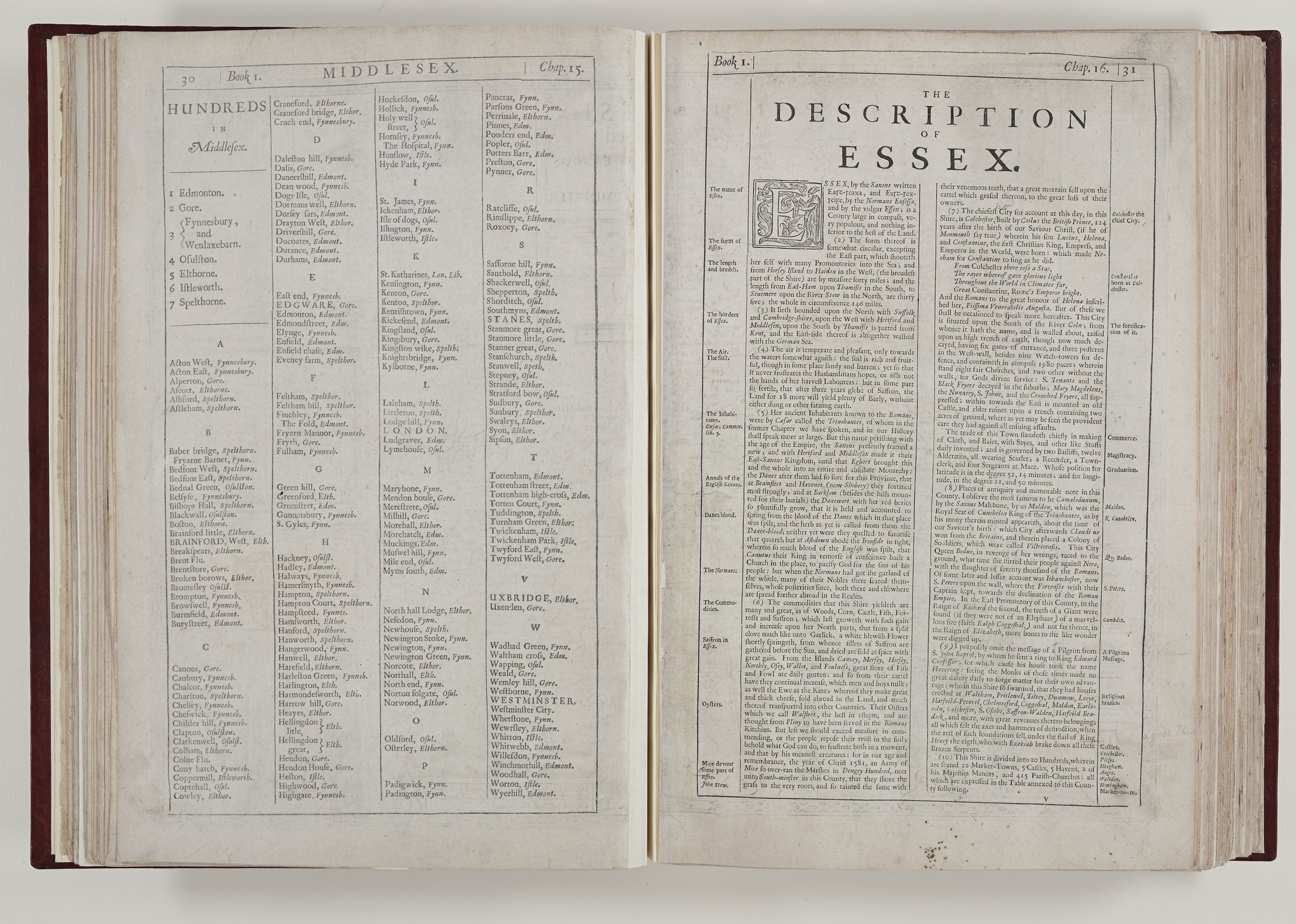

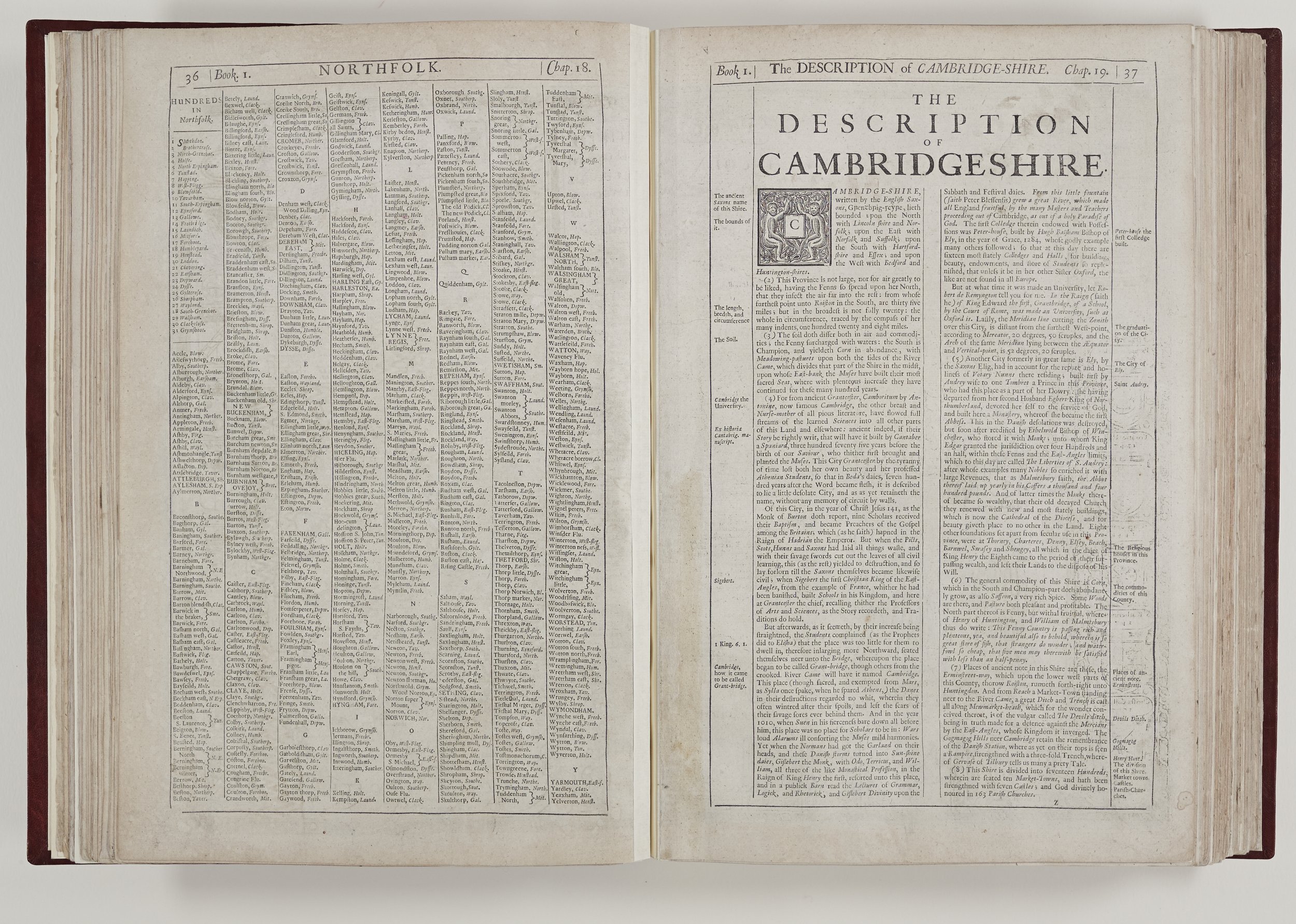

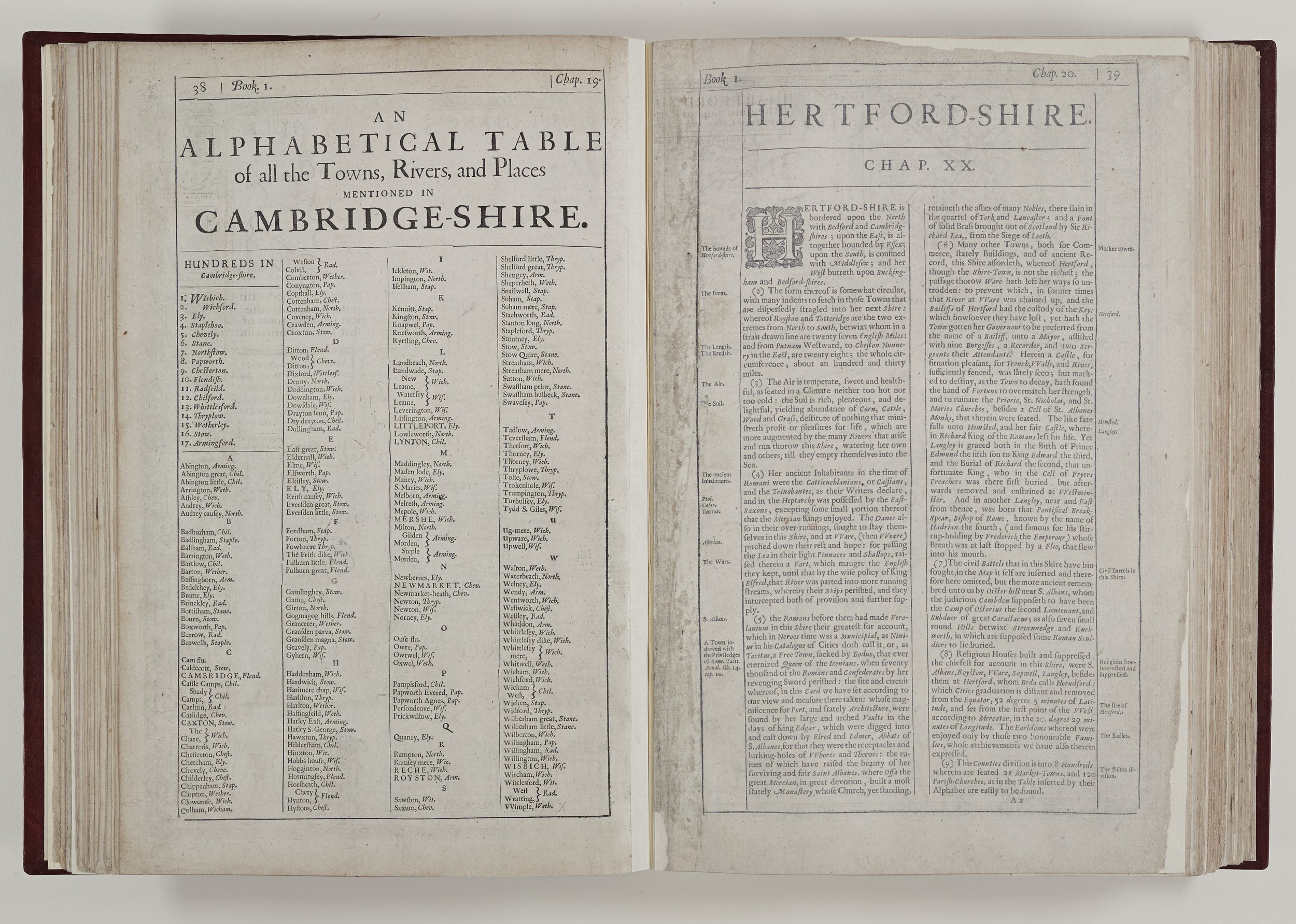

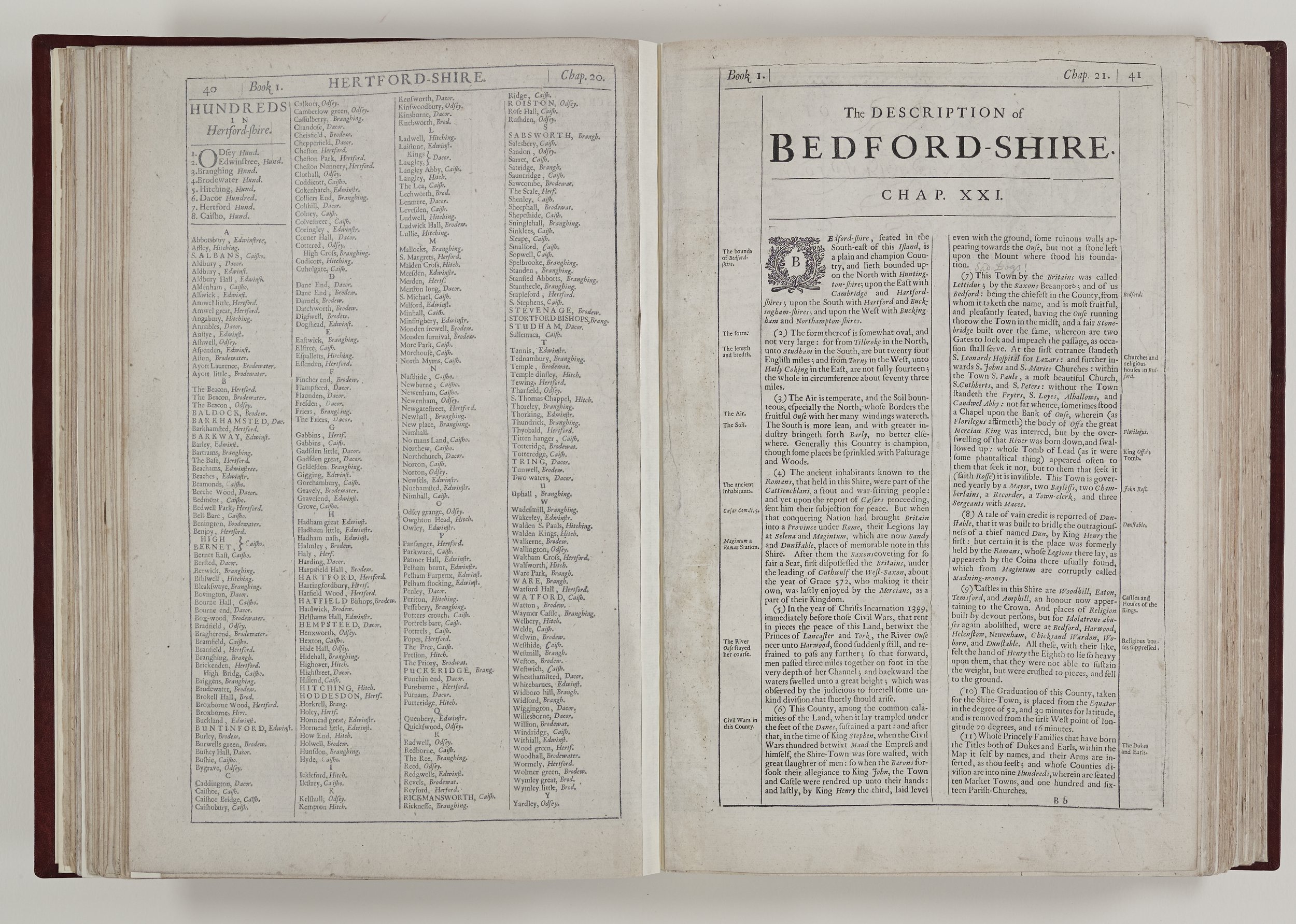

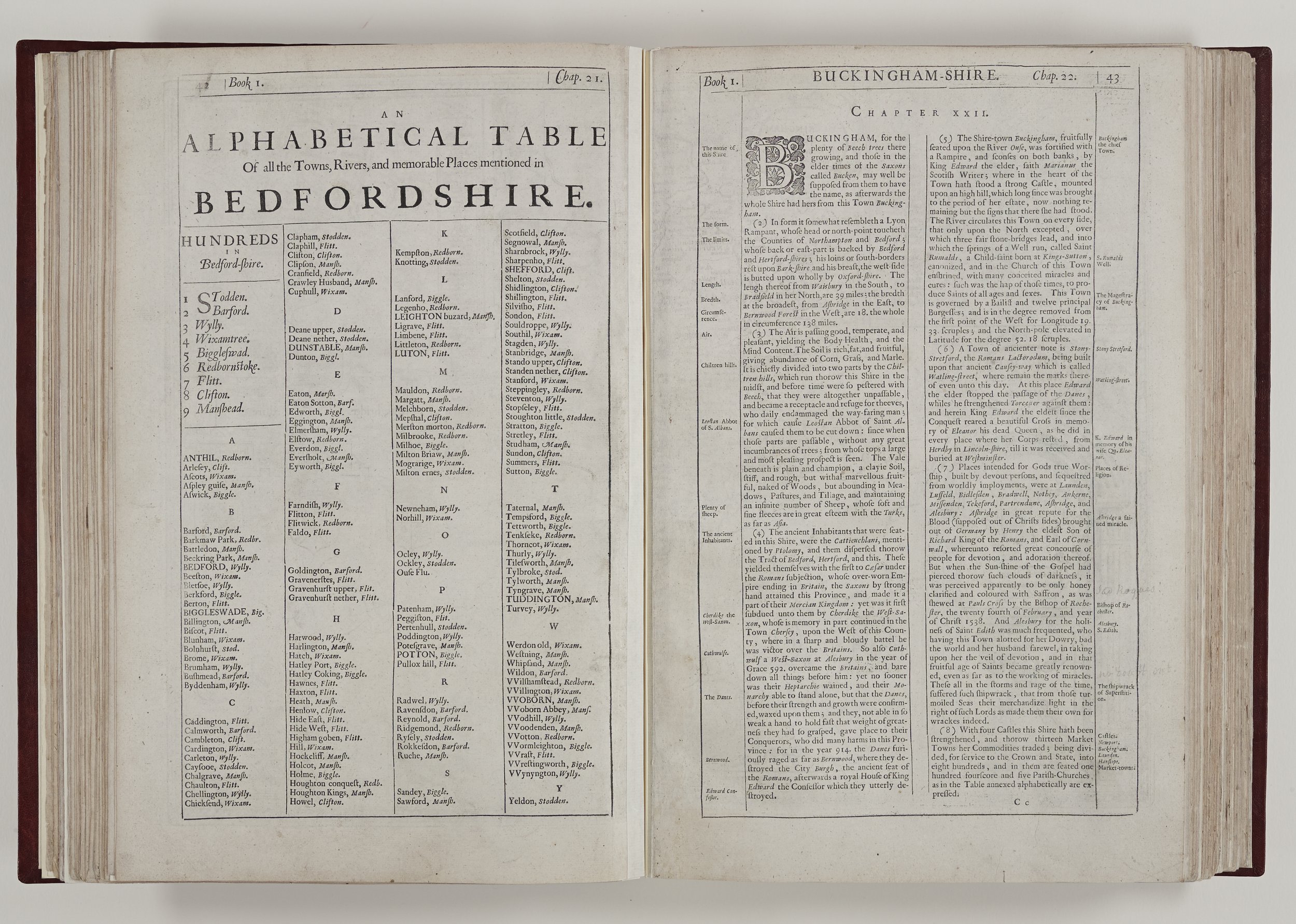

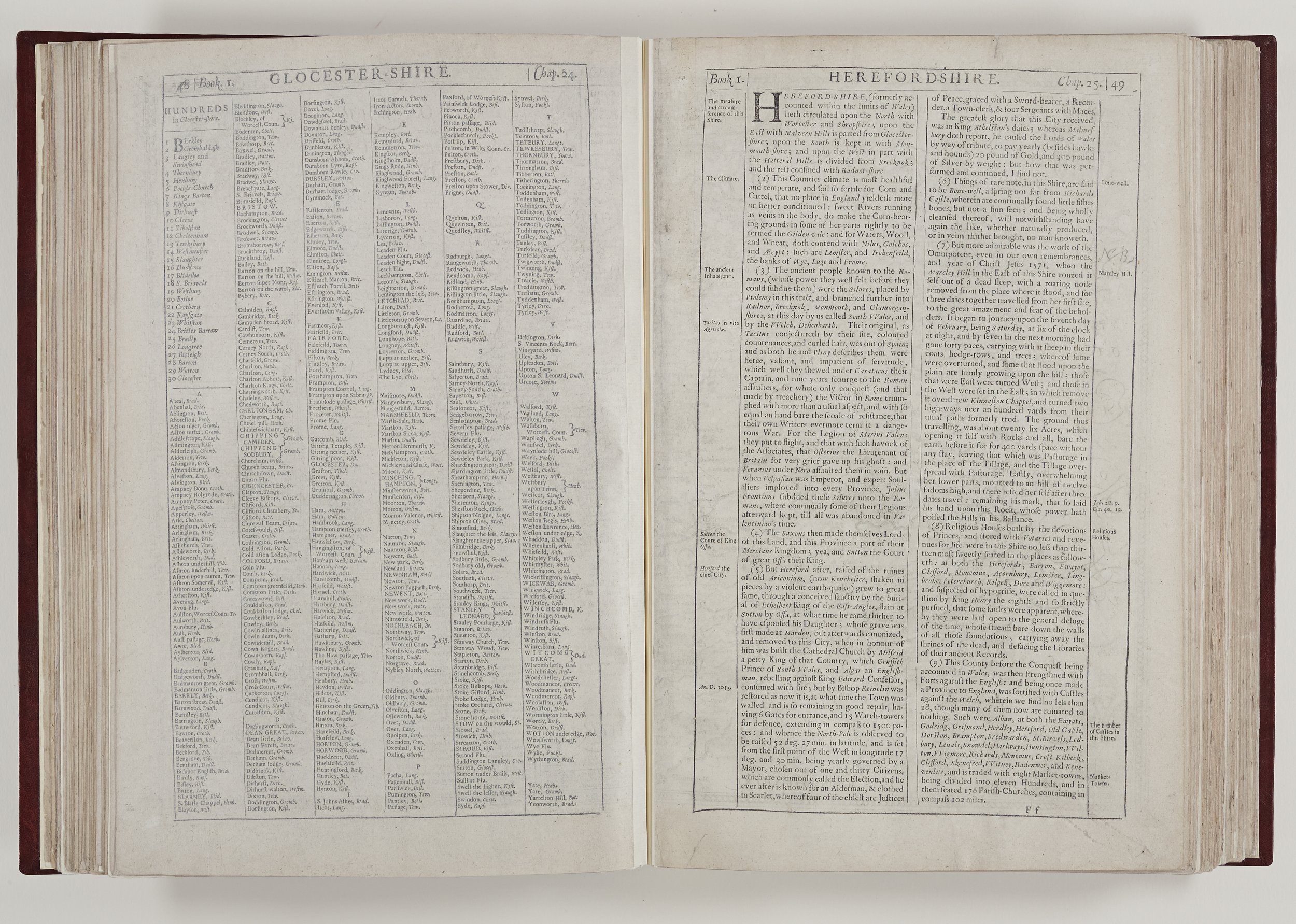

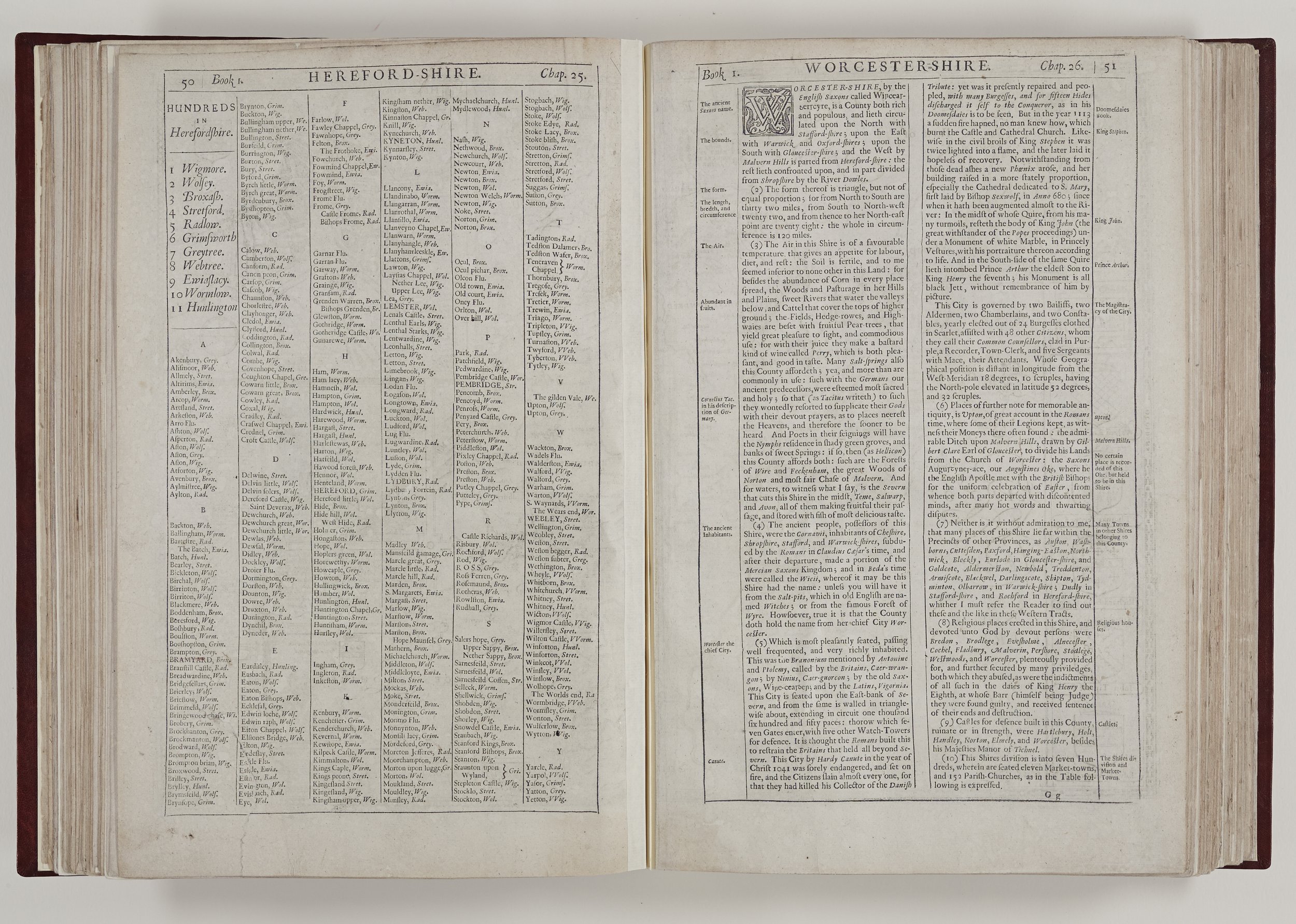

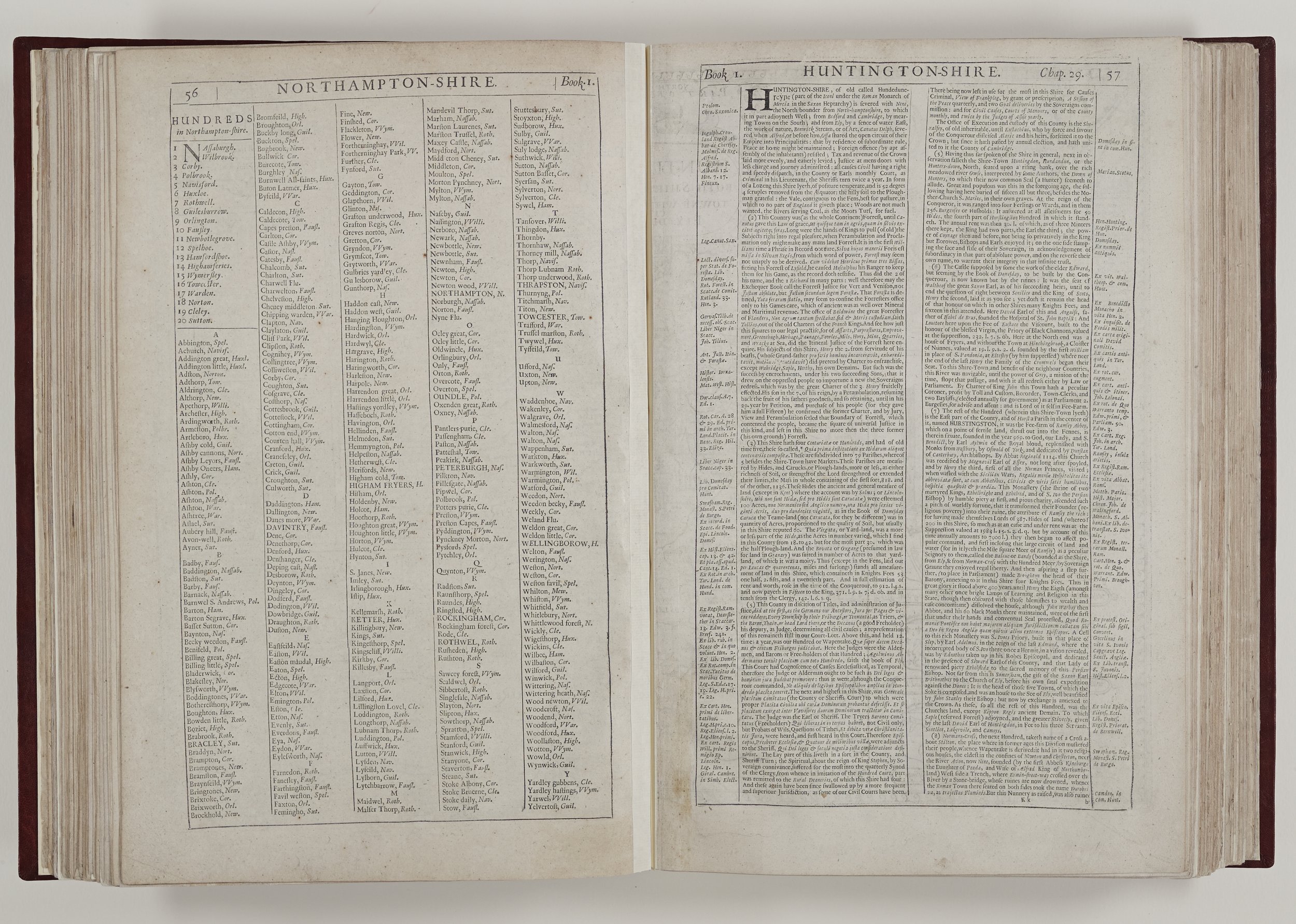

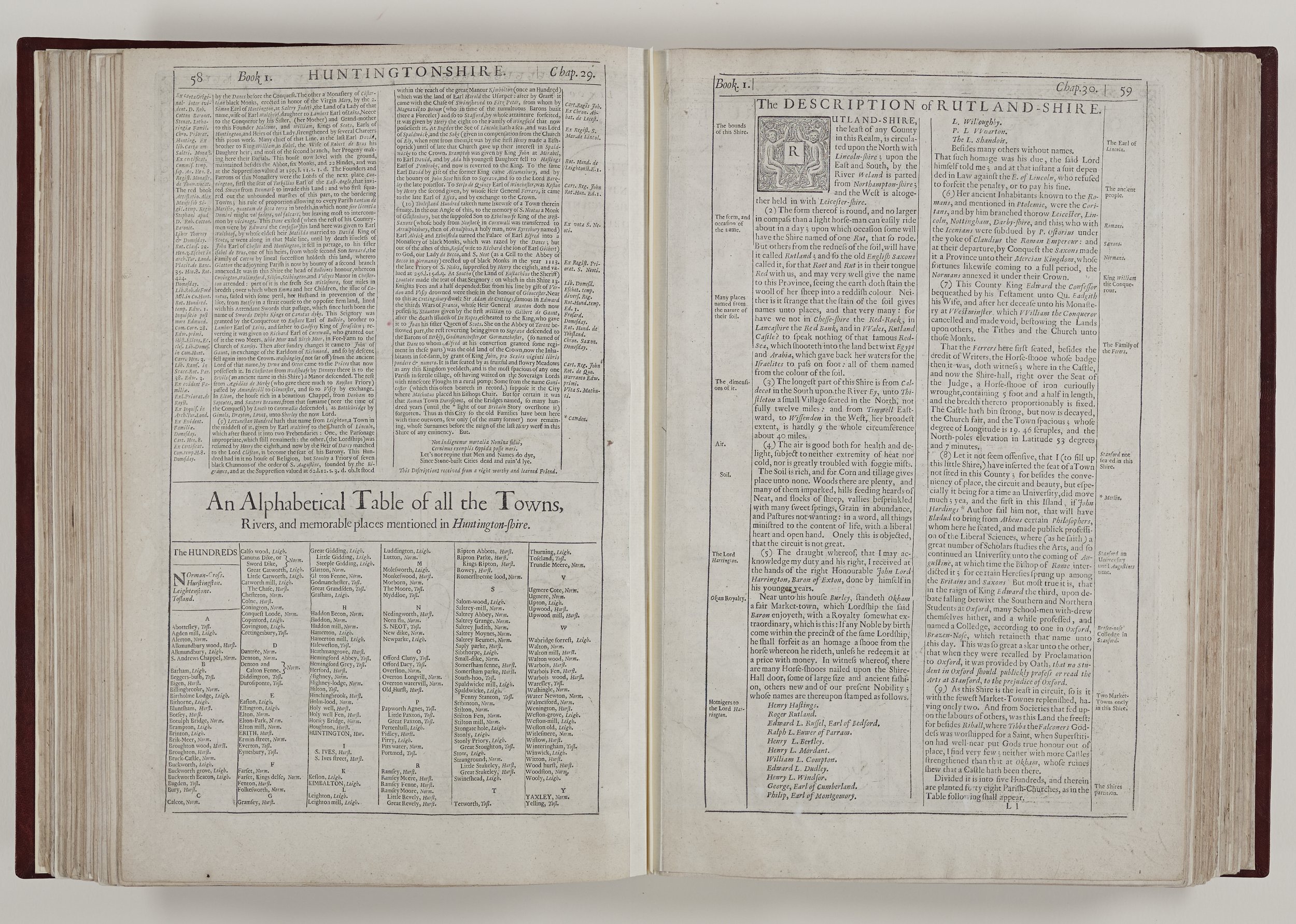

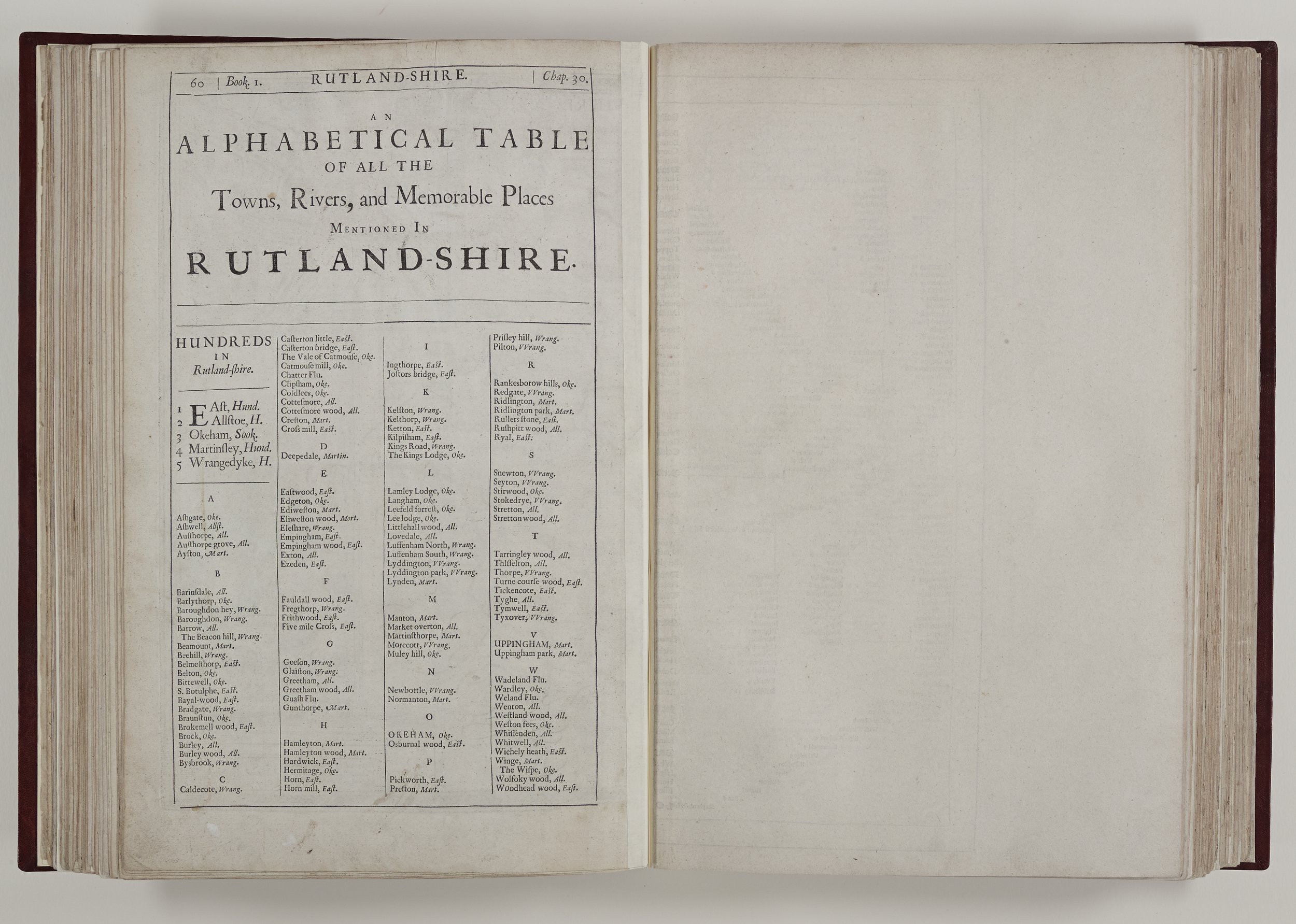

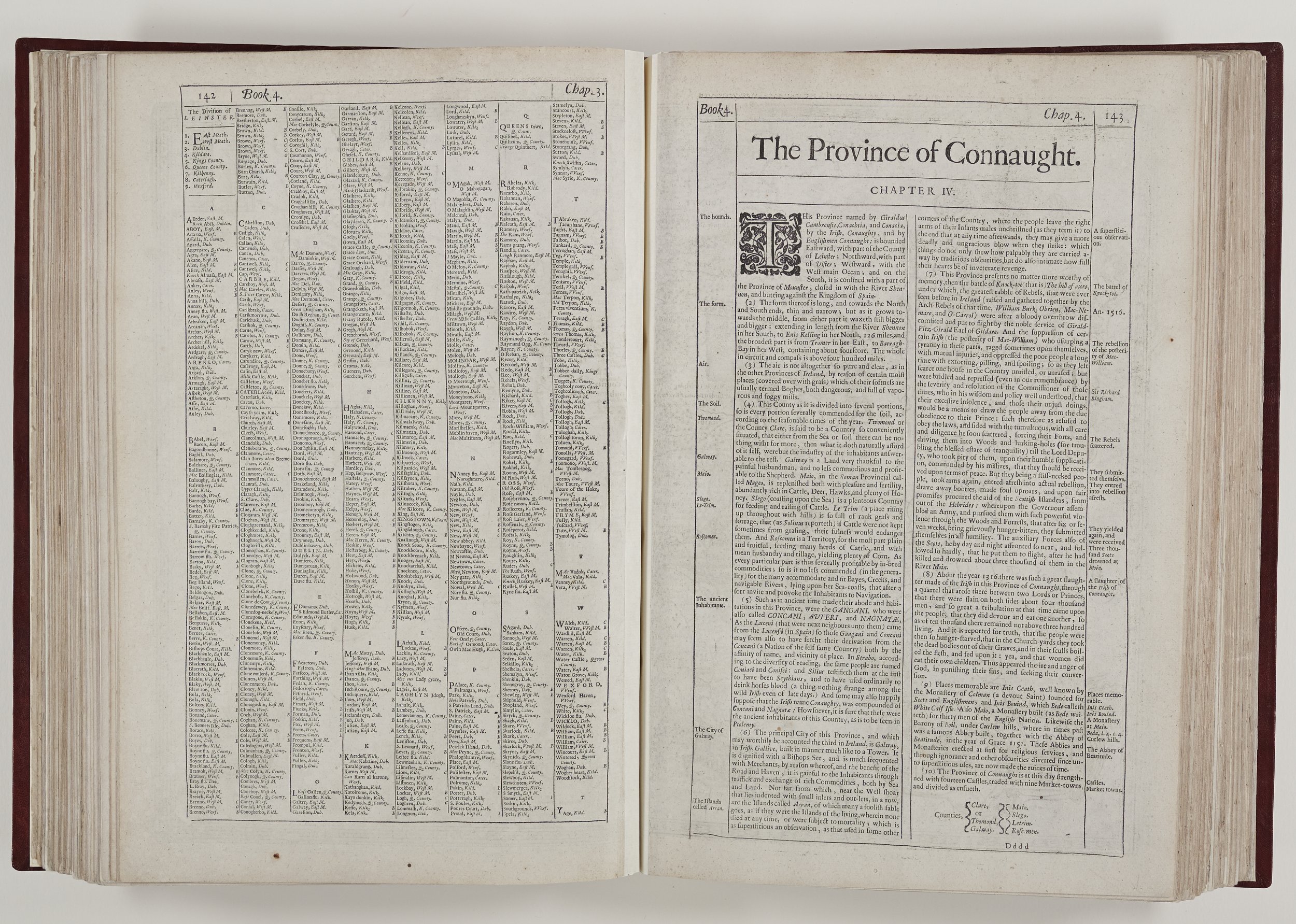

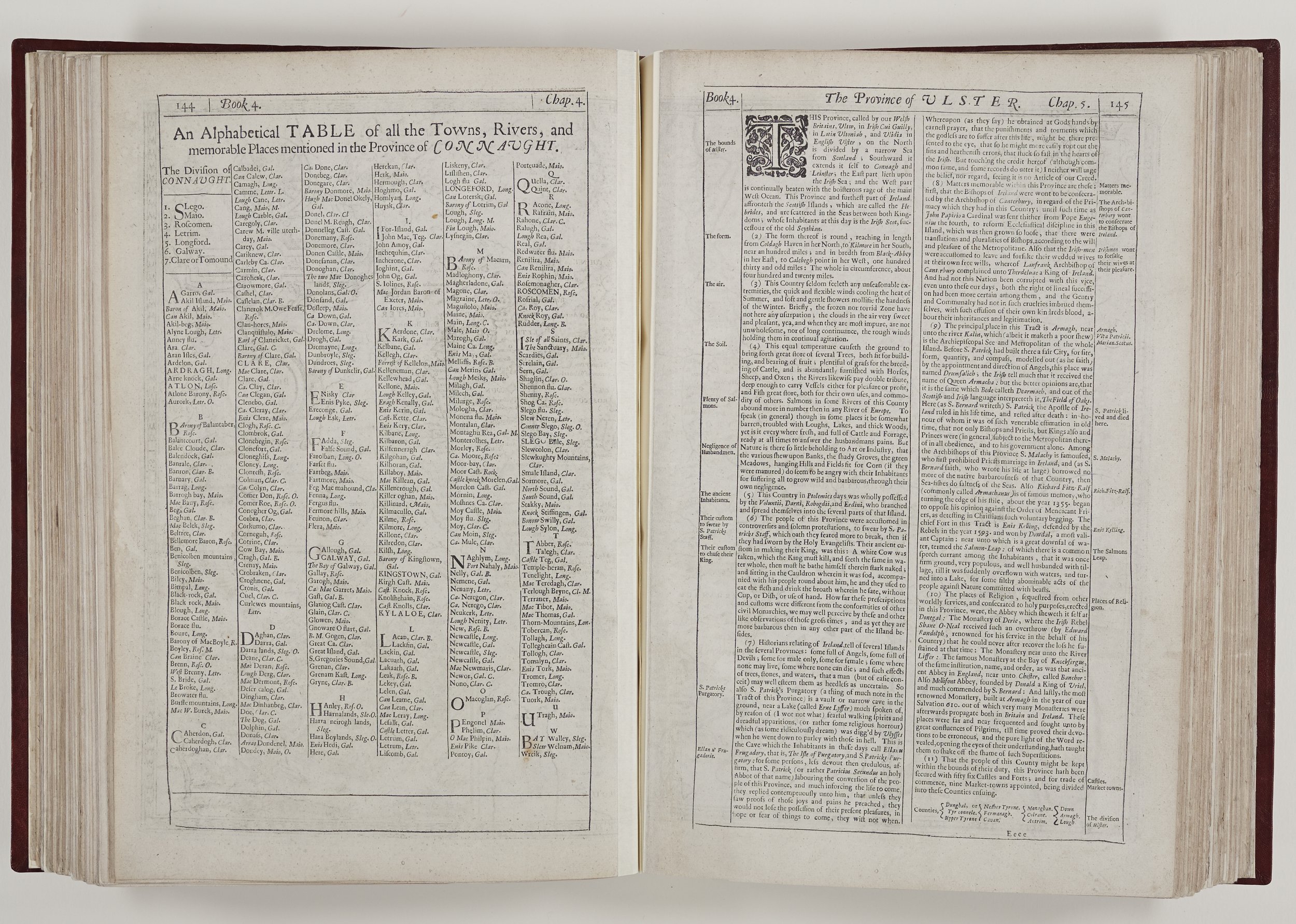

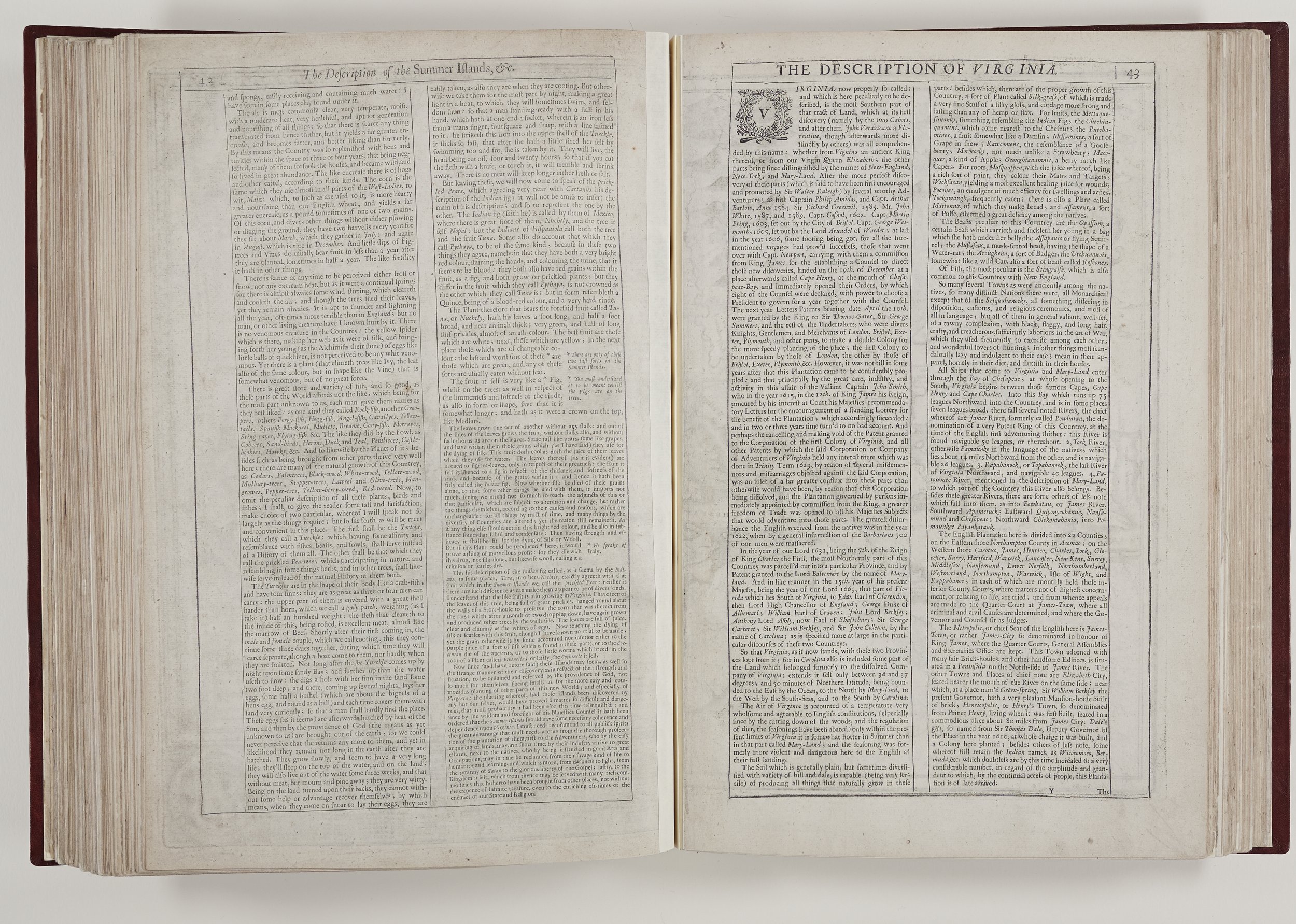

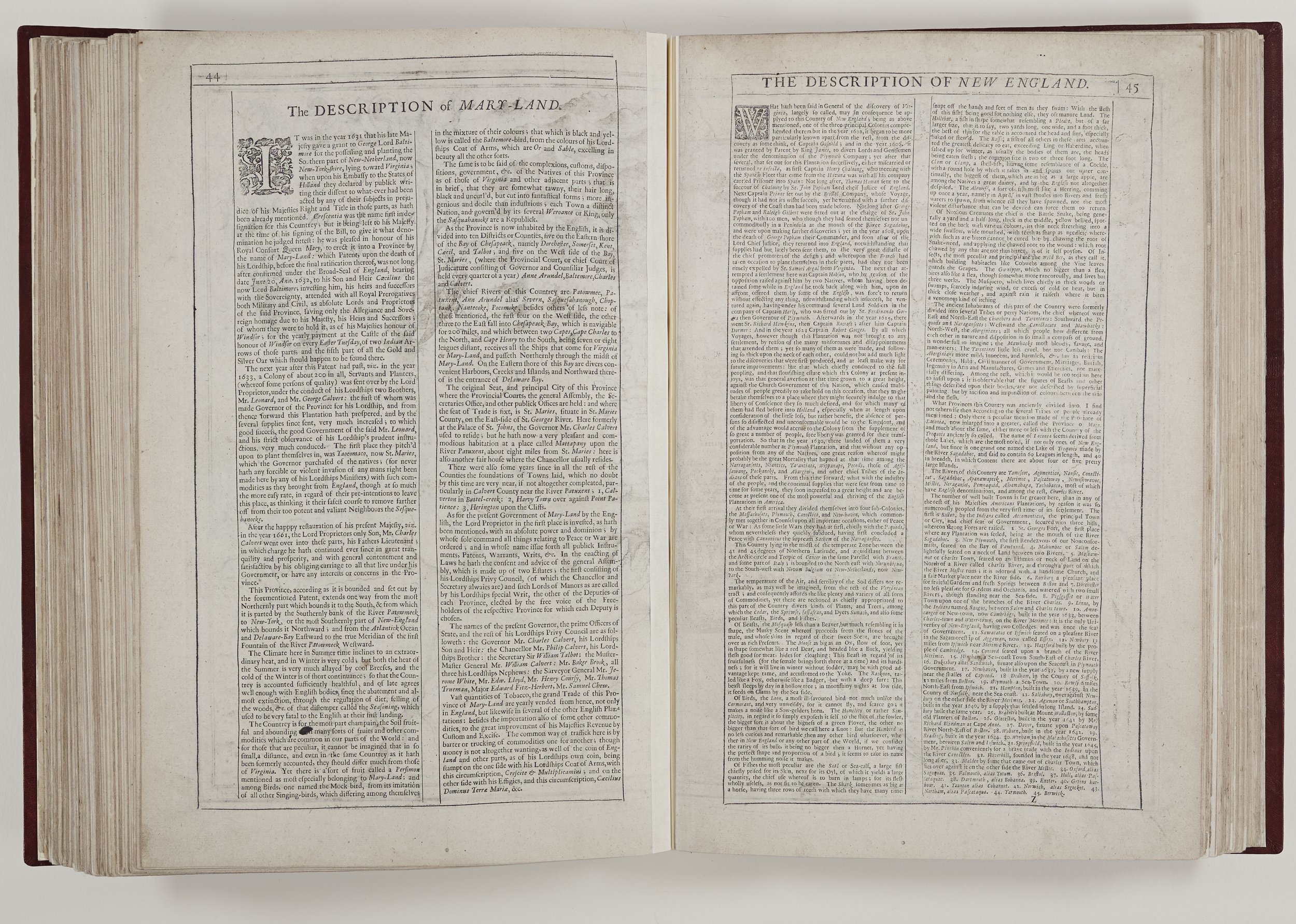

Nearly all counties in the Theatre have a description, a double page spread map and a page of divisions and principal towns. Speed systematically describes the geography of the county giving an indication of its weather and air quality – an important indicator then as now with regard to health. Coastal areas however could provide air which was “piercing and sharp” and from his words, it is easy to imagine Mr Speed caught travelling on a drizzly, blustery day in Cornwall. However, Speed asserts that the air quality on the Isle of Wight keeps its inhabitants young as “witnessed by the long continuance of the inhabitants in the state of their bodies before they be decayed.”

Speed gives details of farming, fishing and industry. He writes about mining for coal and lead in various parts of the country, such as Derbyshire where he states that alongside lead can be found veins of antimony, which “Alchymists hold…in great esteem.” Other interesting minerals include emery, used for cutting and polishing gemstones, which could be found in Guernsey. He writes of tin and even diamonds being mined in Cornwall and in the estuary of the River Irt in Cumberland, mussels “gaping and sucking in dew” which produced much-prized pearls. The local people “gather and sell these to the Lapideries [people who cut, polish, or engrave gems] to their own little, and the buyers great gain.”

Speed assures us that Worcestershire’s apples produce a perry “which is both pleasant and good to taste.” Liquorice grown in abundance near Worksop, Nottinghamshire, is, he assures us, “very delicious and good.” He covers history from ancient times to the beginning of the seventeenth century and his sources range from Roman historians to antiquarians of his day. He plots the course of the Pictes Wall [Hadrian’s Wall] on the Northumberland map and says there is “more yet to be seen.”

On the Wiltshire map there is an inset of a stone monument which Speed describes as erected by the ancient Briton, Aurelius Ambrosius, in 475 AD to commemorate a day of treachery by the Saxons and which later became a burial ground. We would know it as the prehistoric Stonehenge. Speed endorses the legend that King Alfred was the original patron of Oxford University in the ninth century, differing from the current view that teaching began in Oxford in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries.

There is an evocative description of Mary, Queen of Scots’ tomb in Peterborough Cathedral. When Speed visited it was “spread over with black Velvet” but by the publication of the original Theatre this description was already outdated, as by command of the Sovereign, preparations were in hand to move the Queen’s body to its final resting place in Westminster Abbey.

We are indebted to Speed for inset illustrations he included of long-lost buildings such as Nonsuch Palace and Richmond Palace on the Surrey map and St. Paul’s in London. In the text he often regales the reader with freakish occurrences such as a plague of mice in Essex which caused a fatal illness in many cattle. In Bedfordshire the locals were still talking of the River Ouse which suddenly stopped flowing in 1399, resulting in an enormous wall of water. Men could walk in the deep channel of the river bed In front of this suspended wall of water for three miles – but sadly Speed doesn’t say what happened next! In Herefordshire Speed recounts the story of Marley Hill which moved in February 1571 and travelled for three days “to the great amazement and fear of the beholders.”

It is very noticeable when Speed does not write the text for a county. The description of Huntingdonshire, for example, was provided by “a right worthy and learned Friend” and in contrast, seems less lively and rather lacklustre.

The map of Huntingdonshire also incorporates another Speed trait. He sometimes puts the insets of towns in different counties when he has insufficient room on the correct map. Thus, Ely, in Cambridgeshire appears on the Huntingdonshire map presumably because the former is awash with the coats of arms of nobles and the university colleges - and York is located in the West Riding map of Yorkshire.

Good roads had become increasingly important in the Civil War and following the Restoration, in a period of higher wages and more inter-regional trade, road traffic was increasing. Growing towns and cities needed provisions and the 1555 Statute which had stipulated that parishes were responsible for road maintenance, using unpaid local labour and requisitioned materials, was acknowledged to be very ineffective. In the 1650s parliament passed a bill which gradually started the introduction of toll gates and turnpike trusts. This system, which was by no means a panacea but which offered some improvement, lasted into the nineteenth century. It is interesting to note that given their scarcity and poor condition there are virtually no roads included in the Speed’s original Theatre maps, except a section of the Great North Road which appears on the map of Huntingdonshire and one other junction at Chesterton. Speed does not describe roads for the traveller in his text for each county in The Theatre, so the six double pages of Principal Roads are a true innovation for this edition.

More market towns are included in this edition and coats of arms of the current noble families are added. Since 1612 some of the fiercest fighting ever seen on British soil had taken place in the Civil War and therefore there is A Continuation of Battels… to this present time. The Prospect also boasts additional world maps demonstrating the expansion of British dominions.

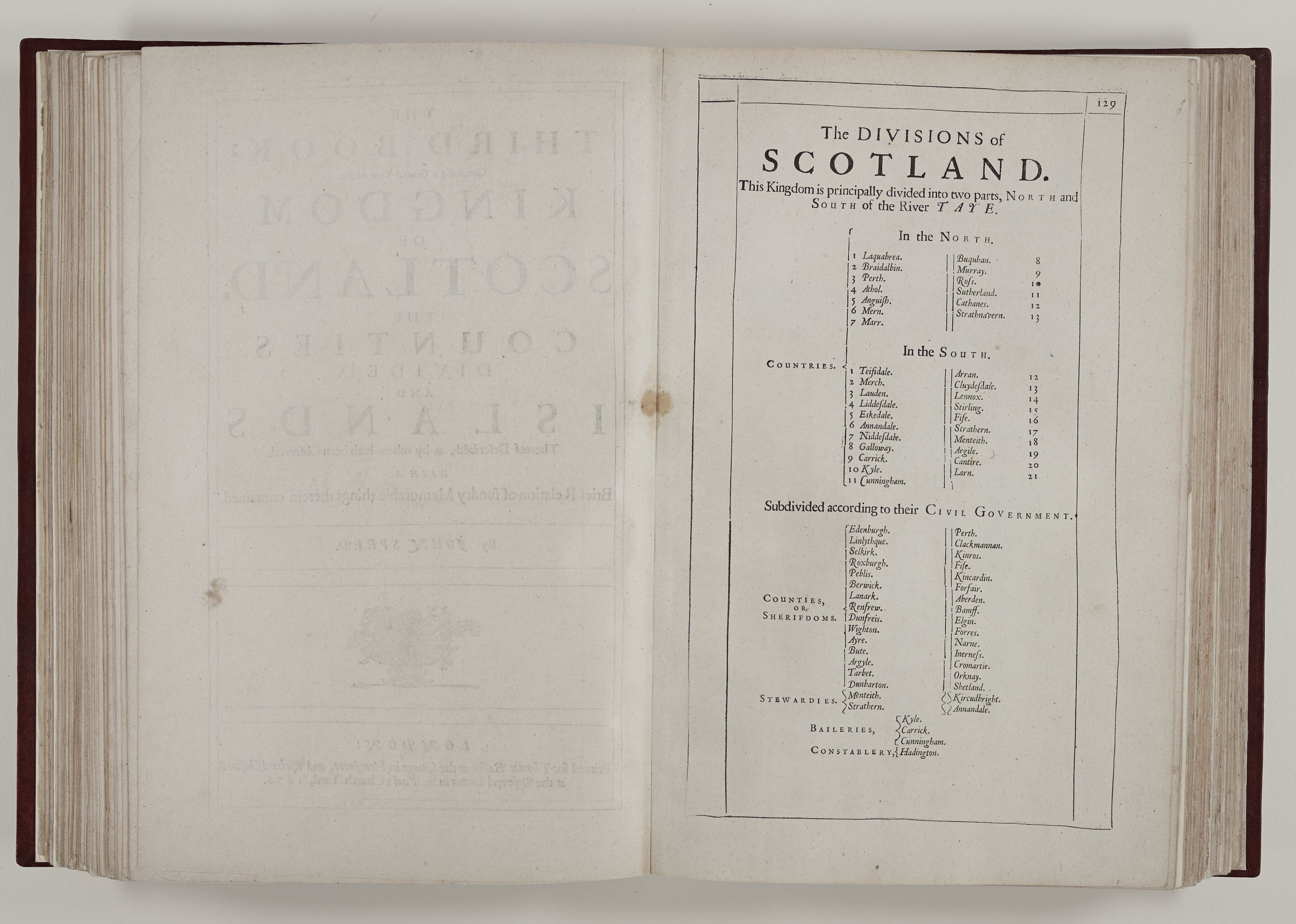

Kingdoms of Scotland, Wales and Ireland

Speed’s Welsh maps were a huge improvement on the work of previous cartographers such as Saxton and he makes the decision to include Monmouthshire in Wales, even though it was administratively English, but Welsh speaking. He is also careful to use the Welsh cantrefs and commotes when writing of subdivisions. It appears Speed was denied some access to municipal records in Wales but his description show he travelled widely in the Principality.

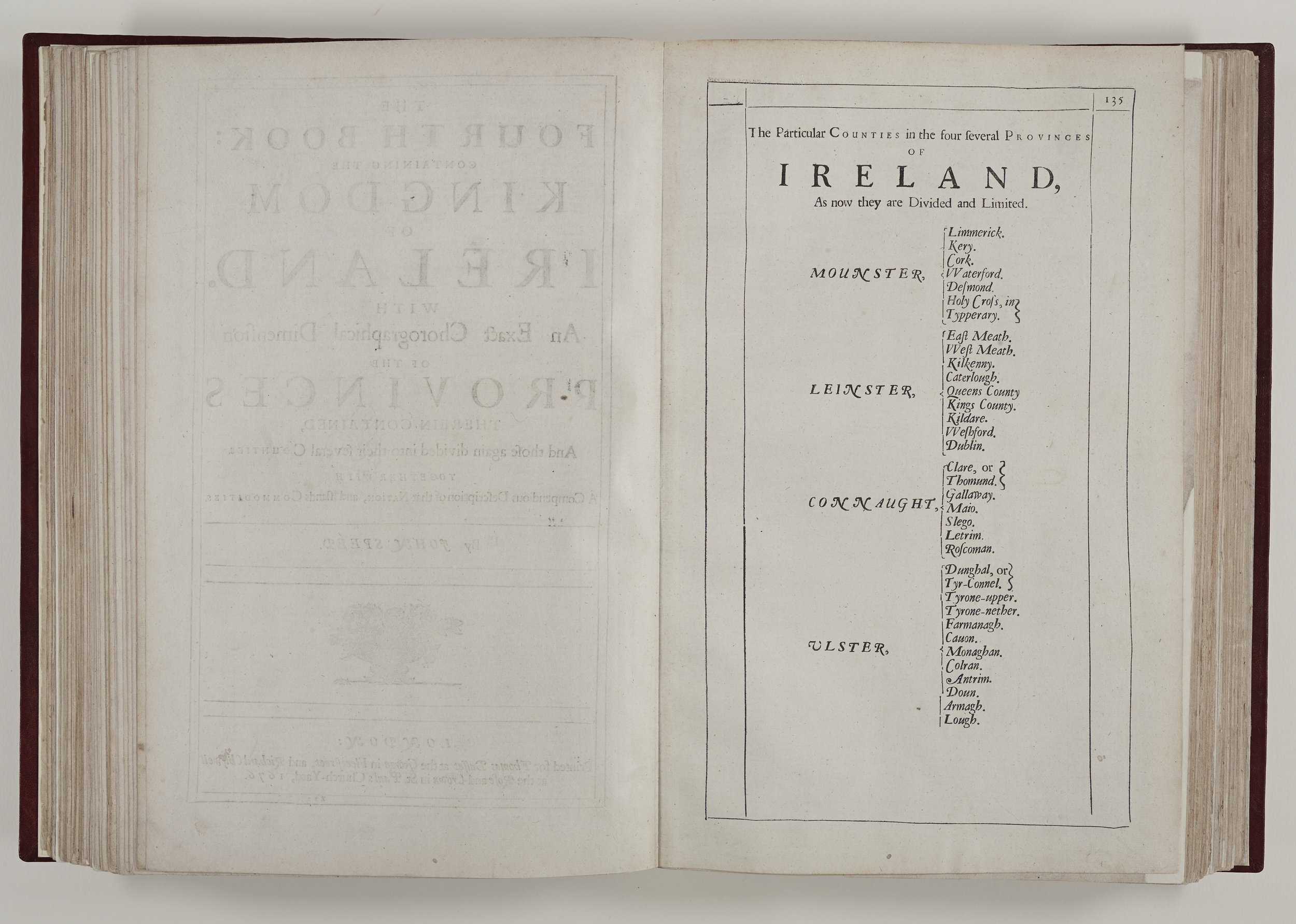

Historians are not so convinced that he travelled widely throughout the whole of Ireland but it is probable that he went to Dublin, which he describes as a beautiful city. He depicts the Irish people in quite striking terms – some being descended from the giants of Nimrod’s race. He is not so keen on areas which he sees as unhealthy “breeding rheums, differenteries and fluxes” but does mention the Irish have a cure for their poor health – uskebah, a wholesome aqua vitae – whiskey.

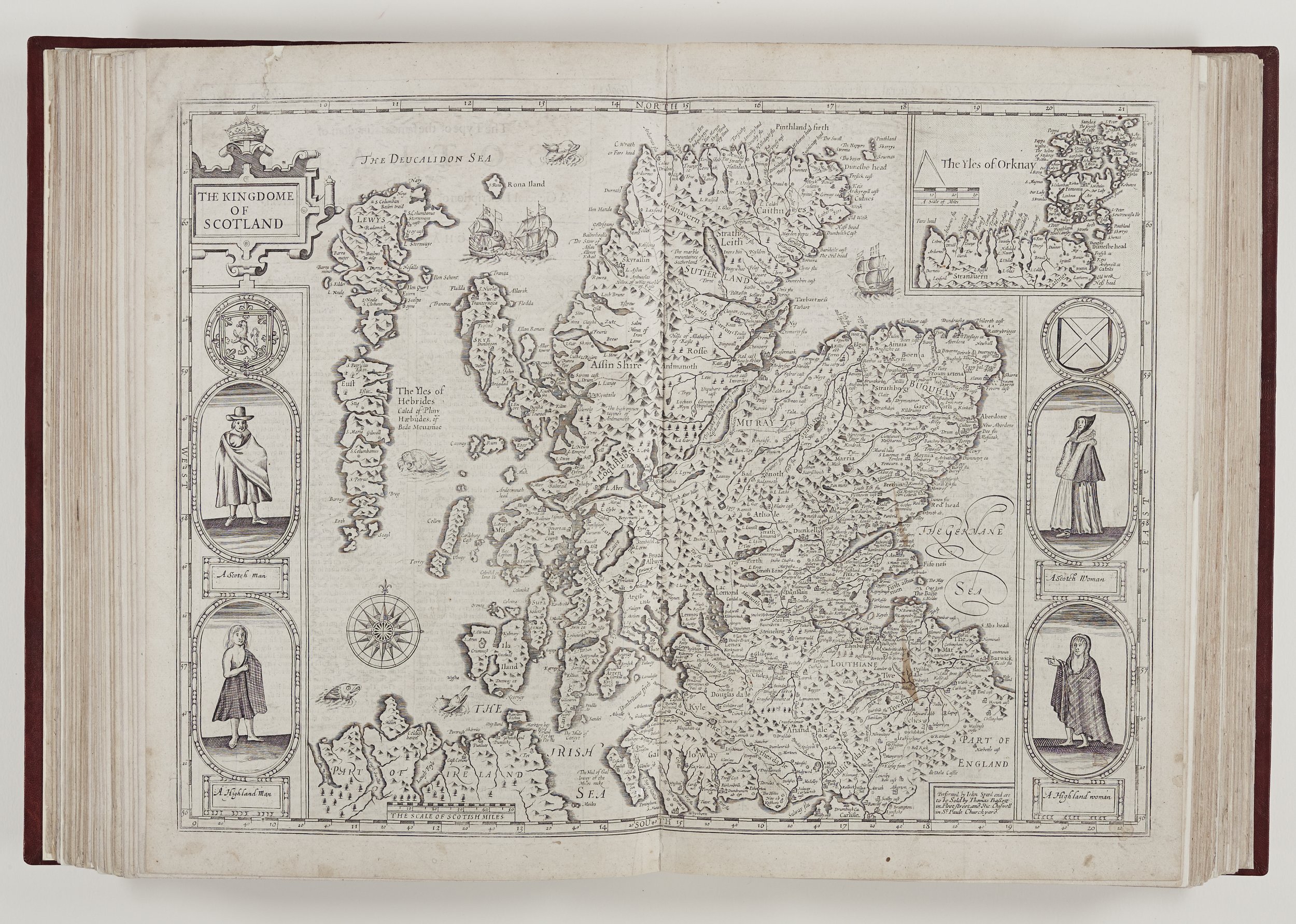

The map of Scotland is based on a 1595 Mercator map and was already known to be inaccurate in Speed’s lifetime. His commentary is limited partly by space and partly by probable lack of first-hand knowledge. However, it would seem Speed was mindful of his Scottish sovereign as he described the southern Scots as strong and intelligent; whereas their northern countrymen retain the ruder characteristics of the wild Irish. I note also that although he talks of Loch Ness never freezing, considering his taste for the outlandish, there is no mention of a monster!

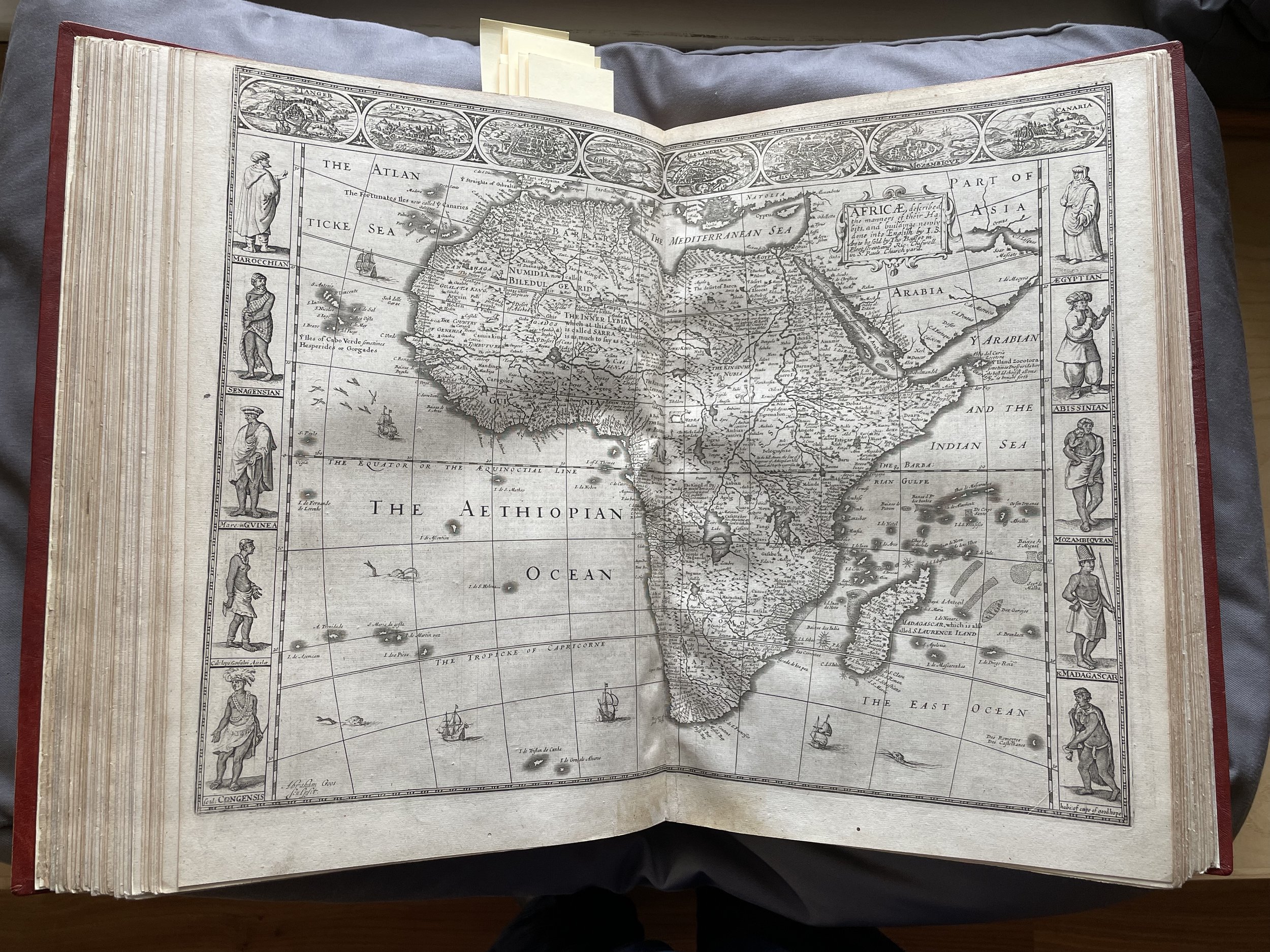

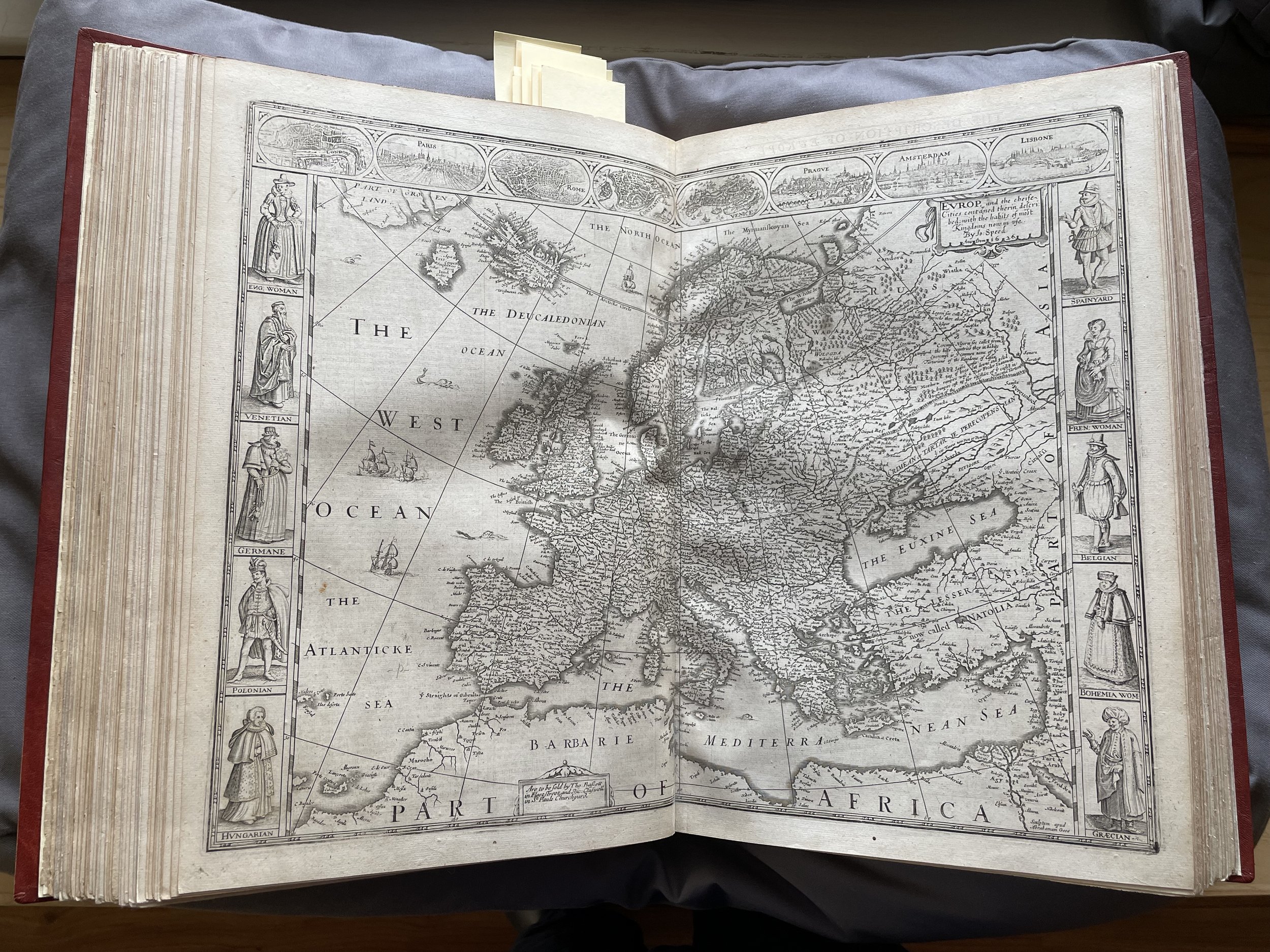

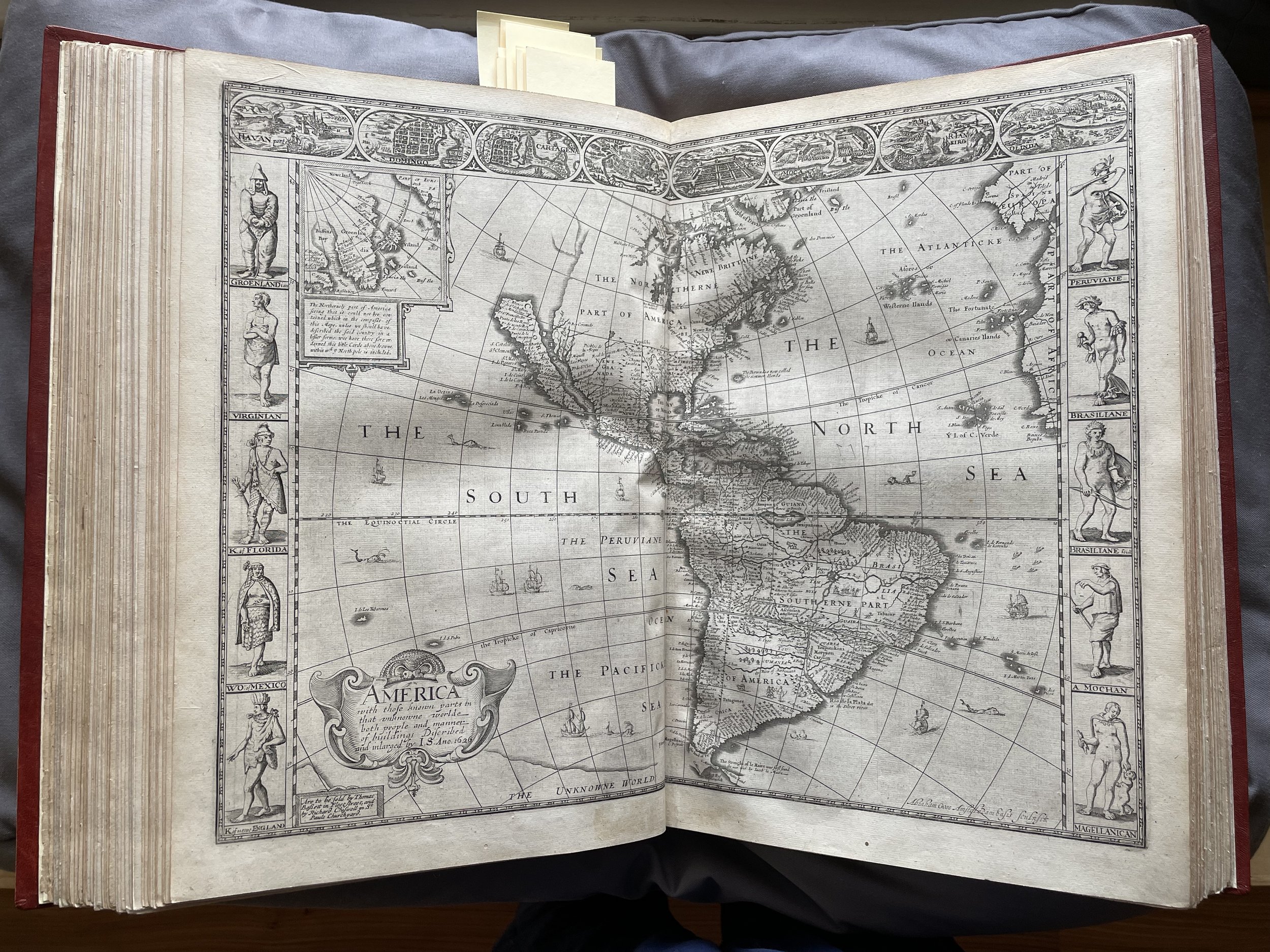

A prospect of the most famous parts of the World

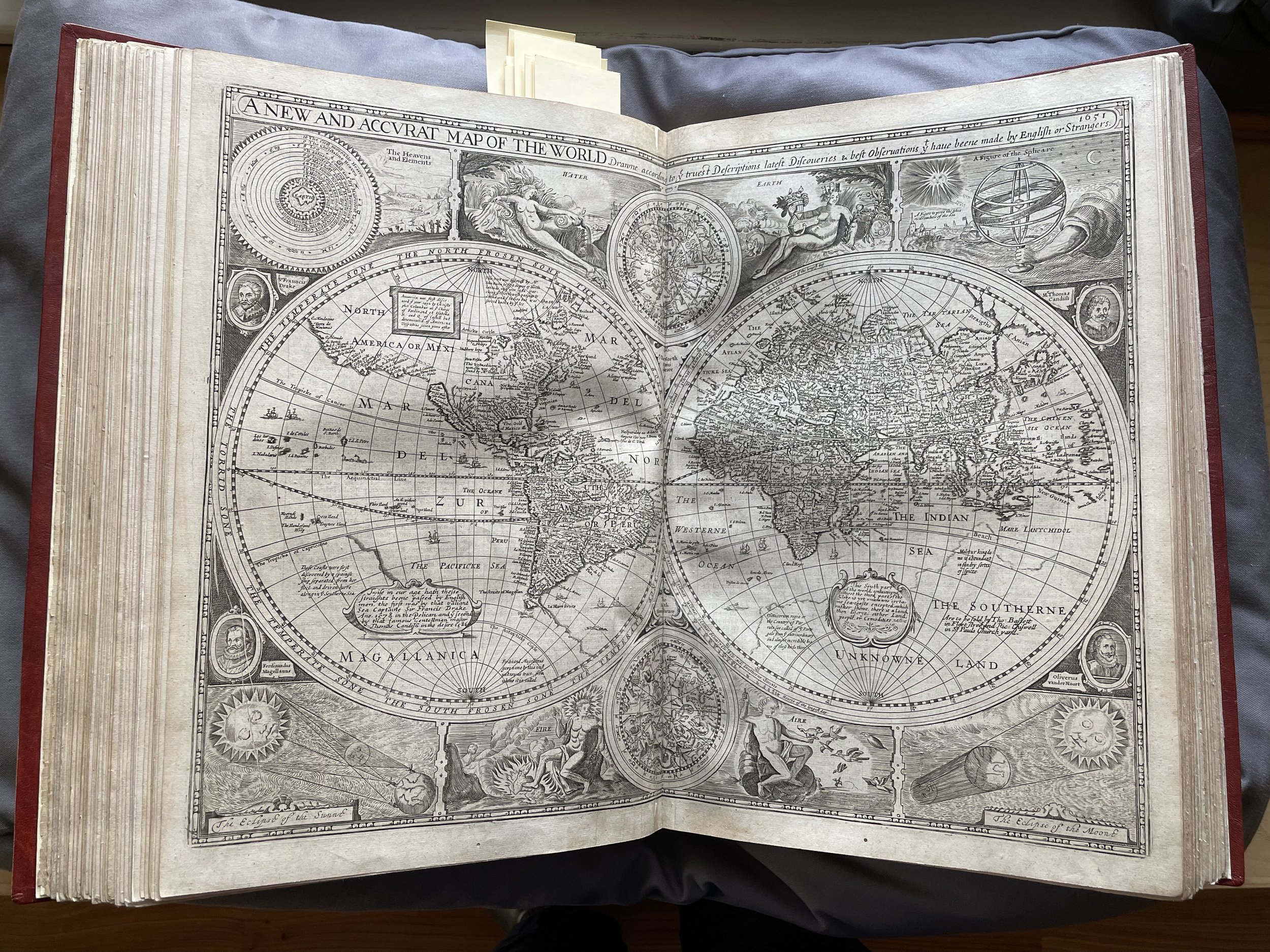

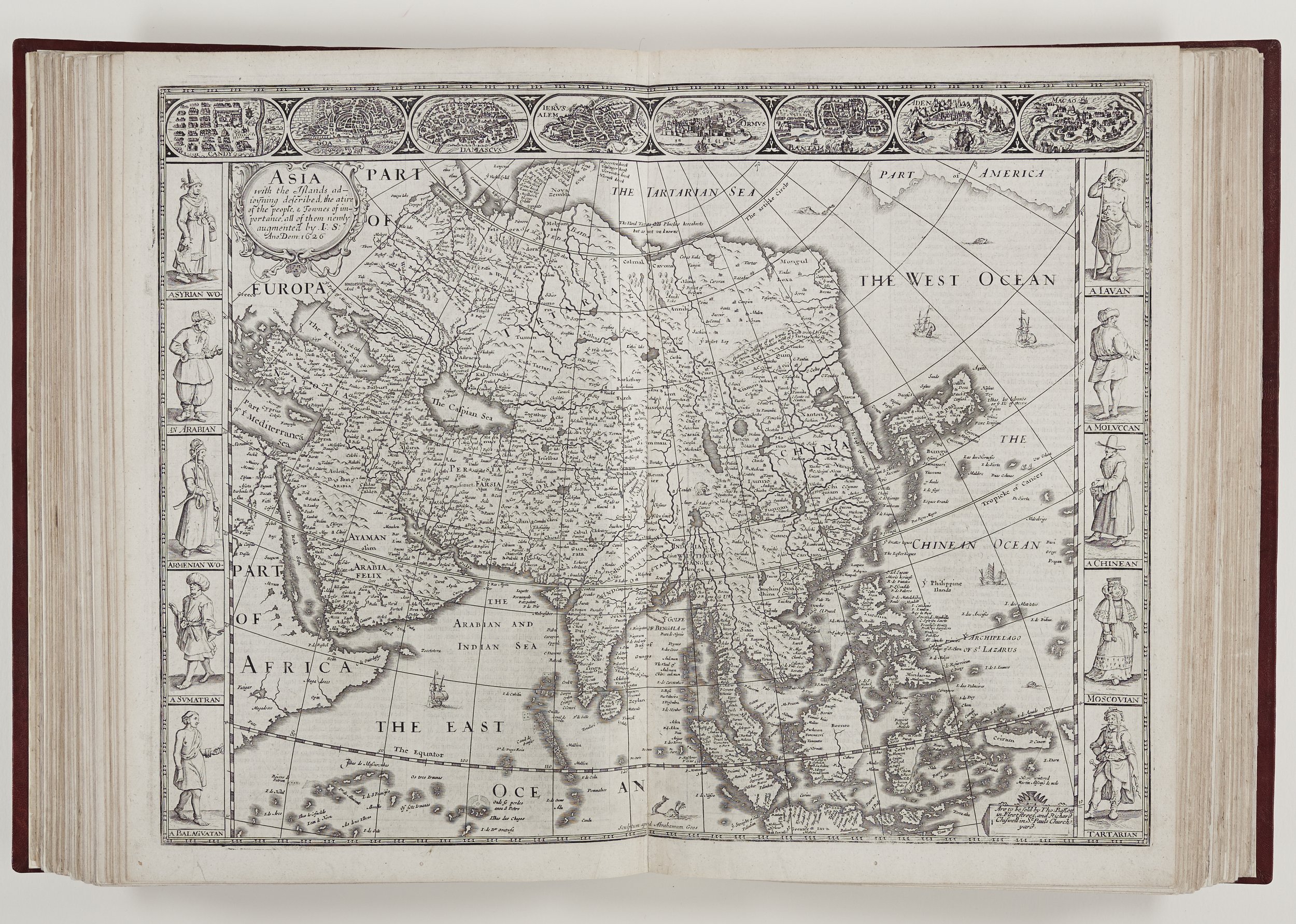

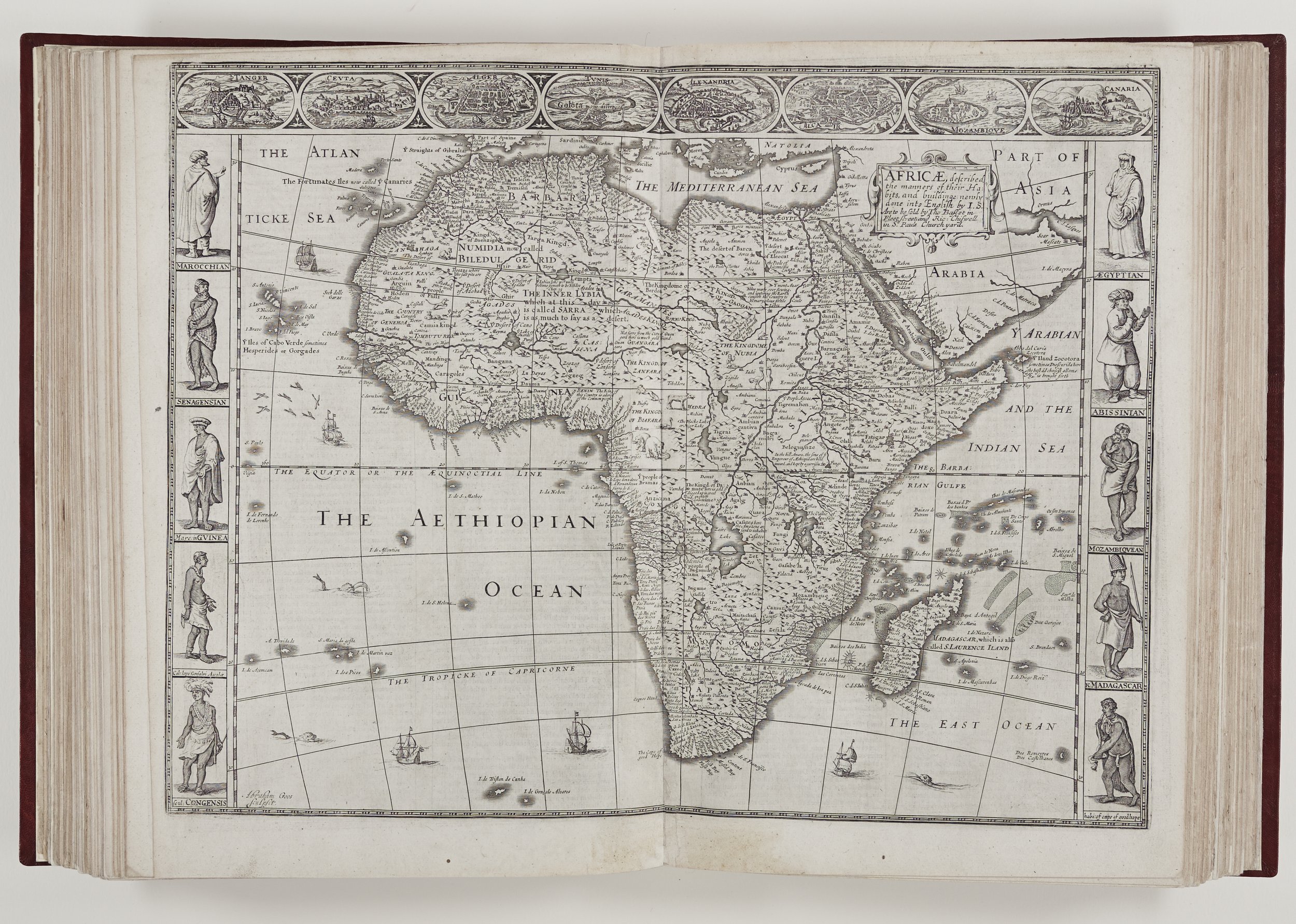

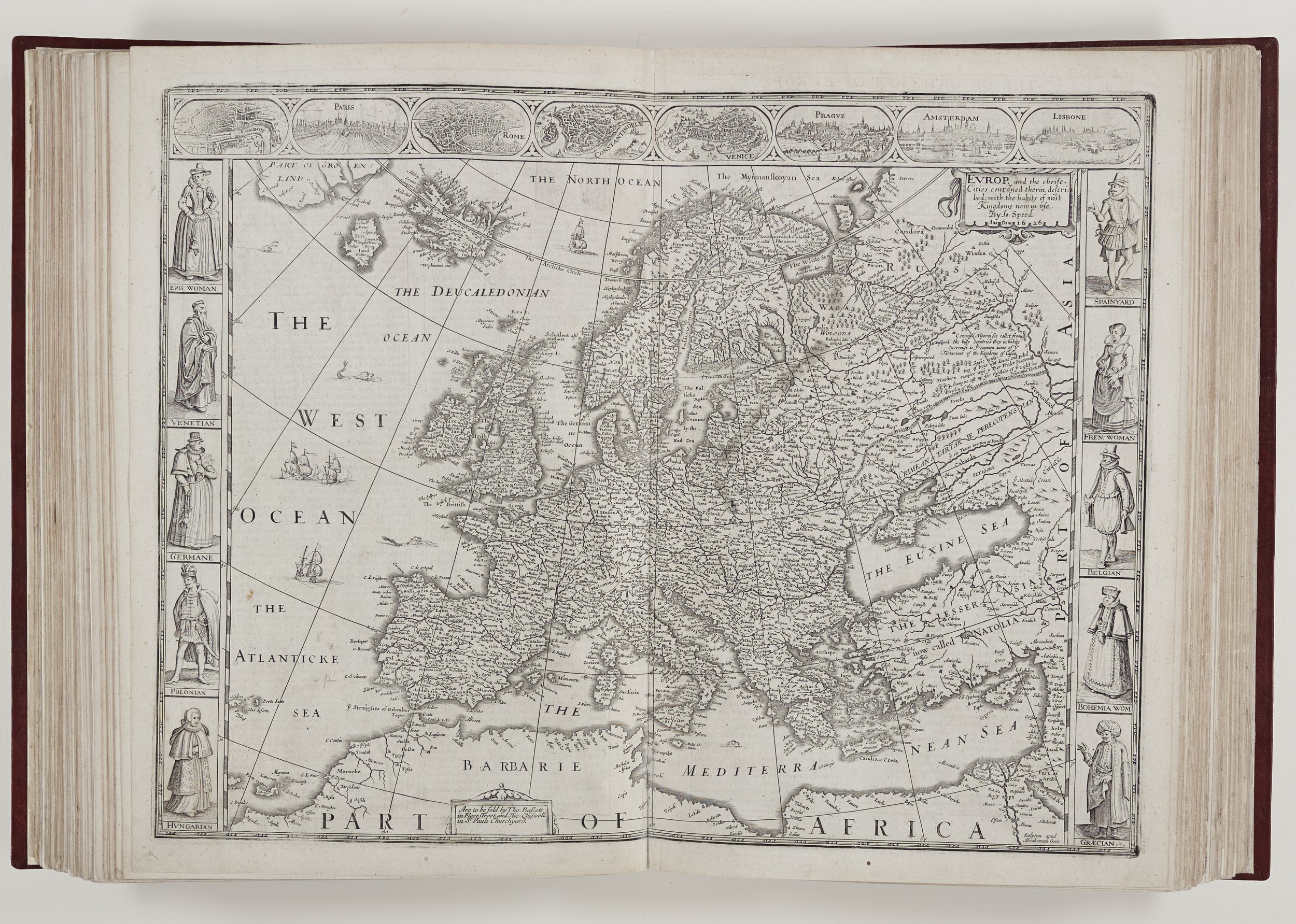

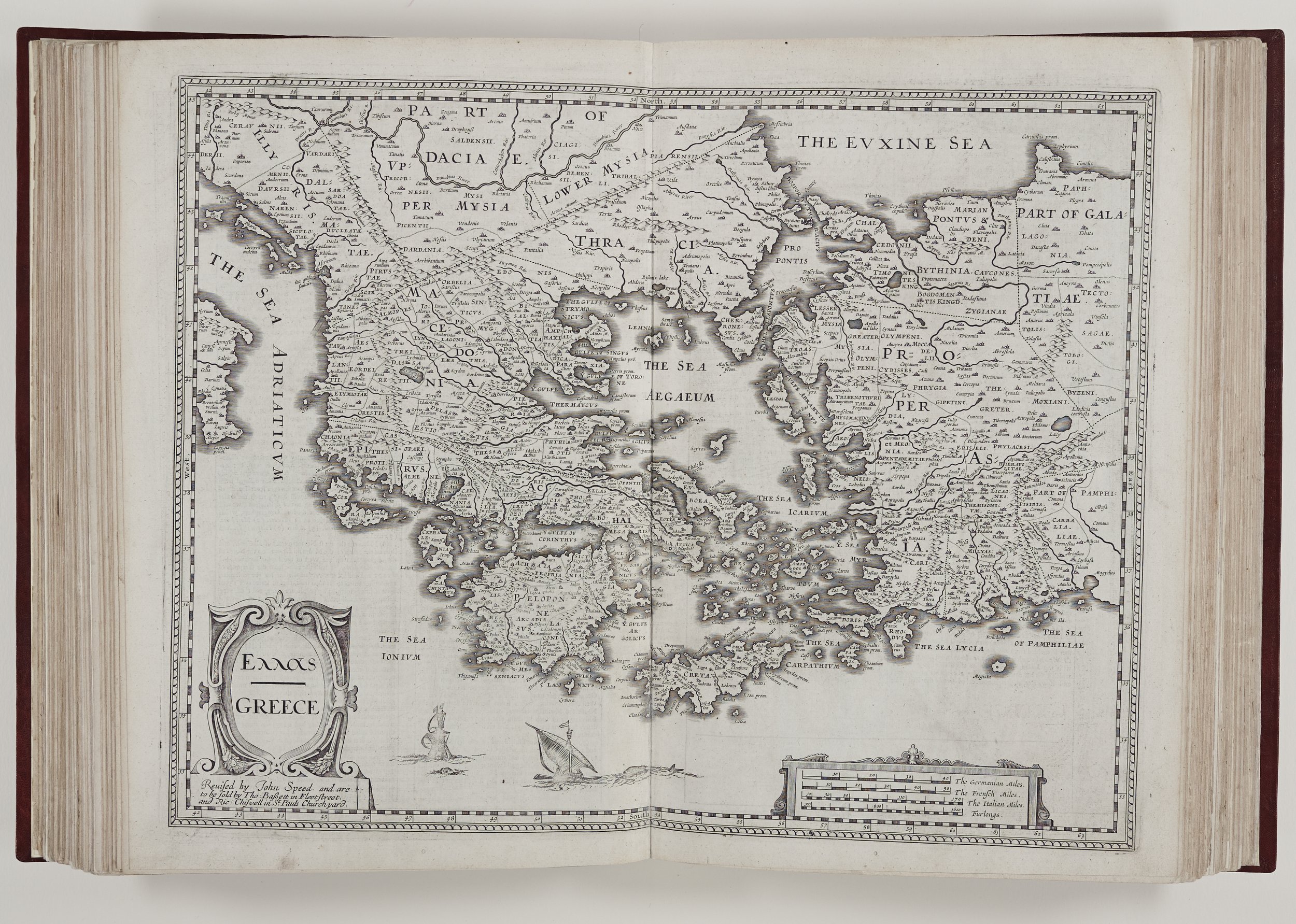

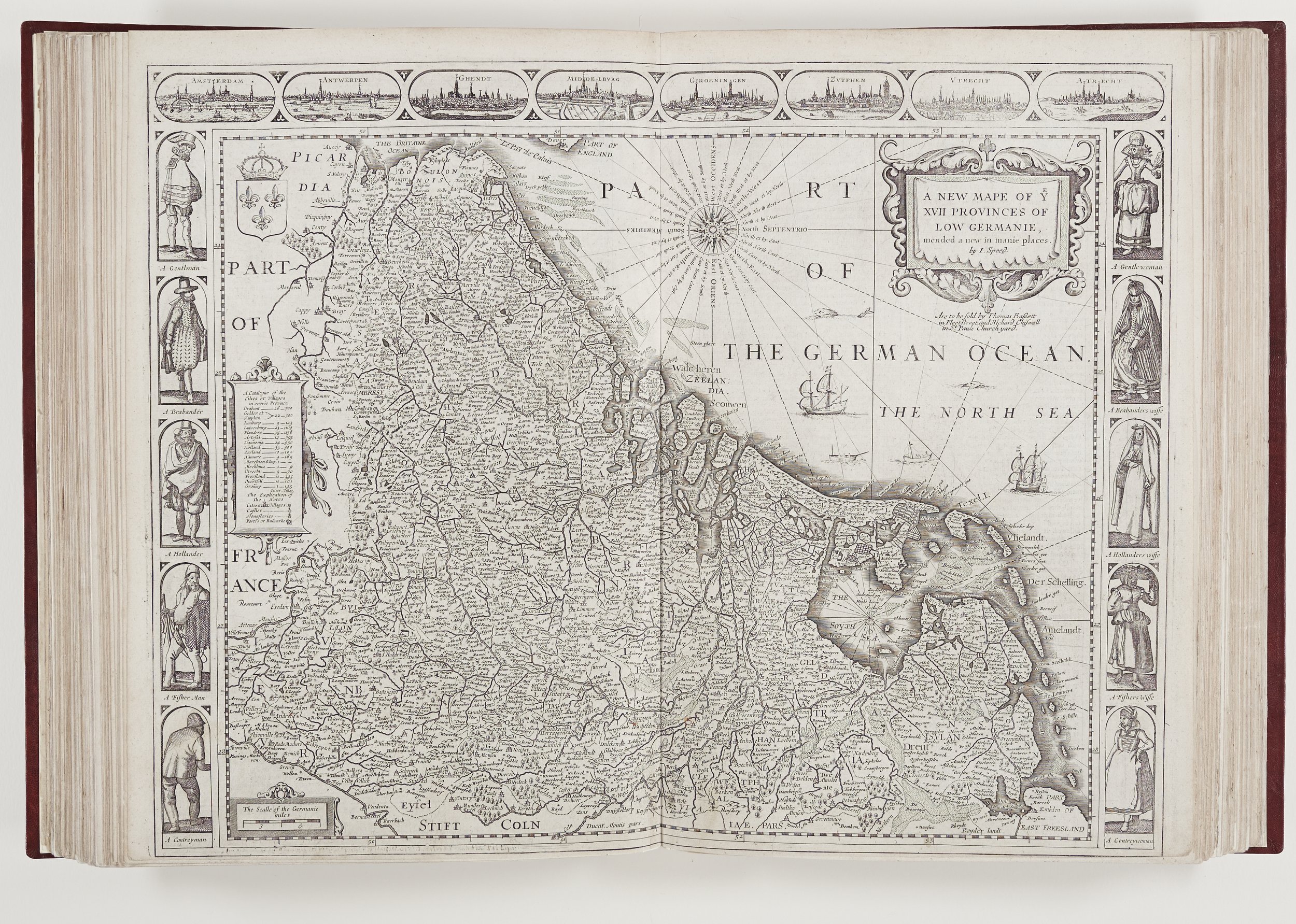

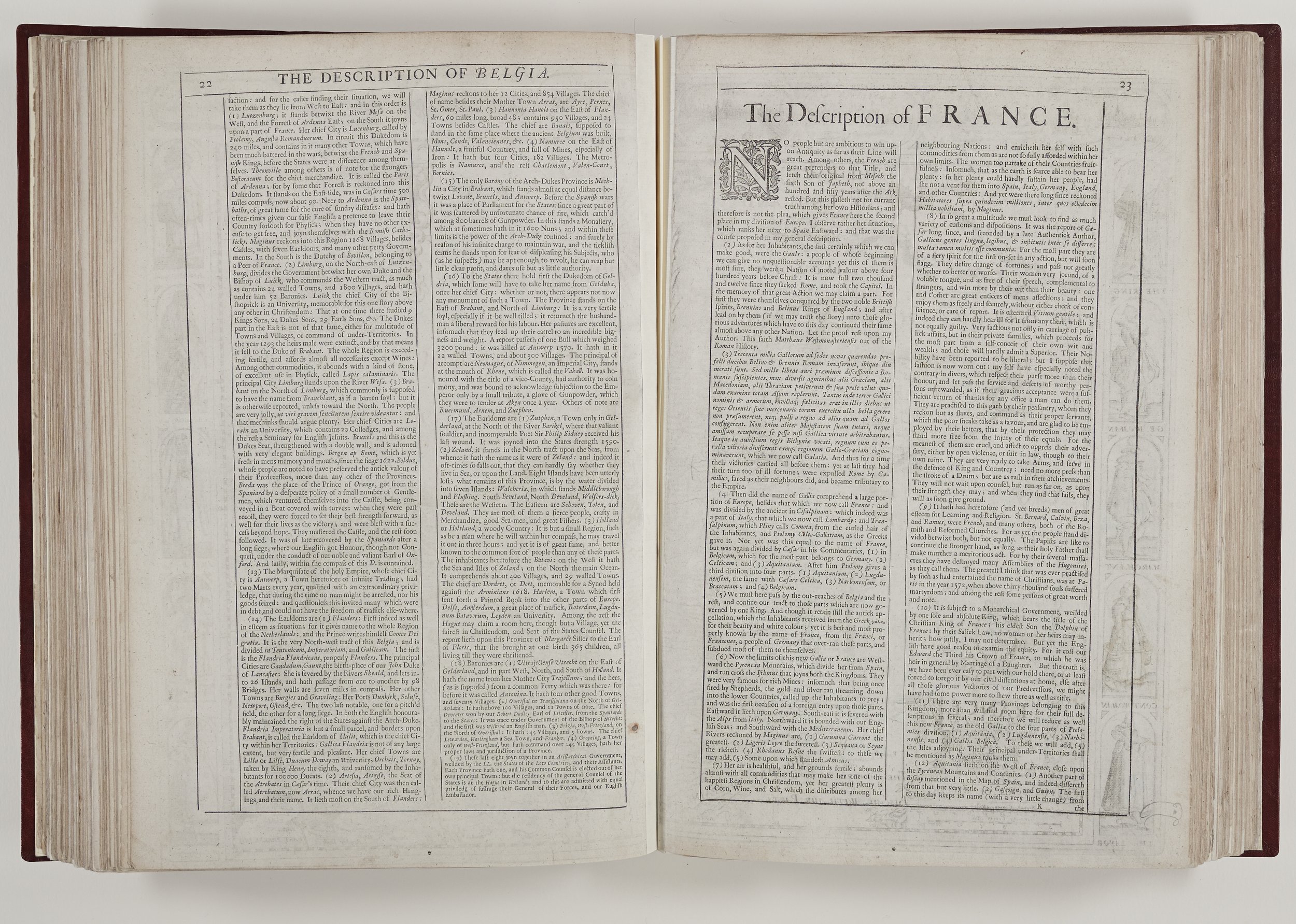

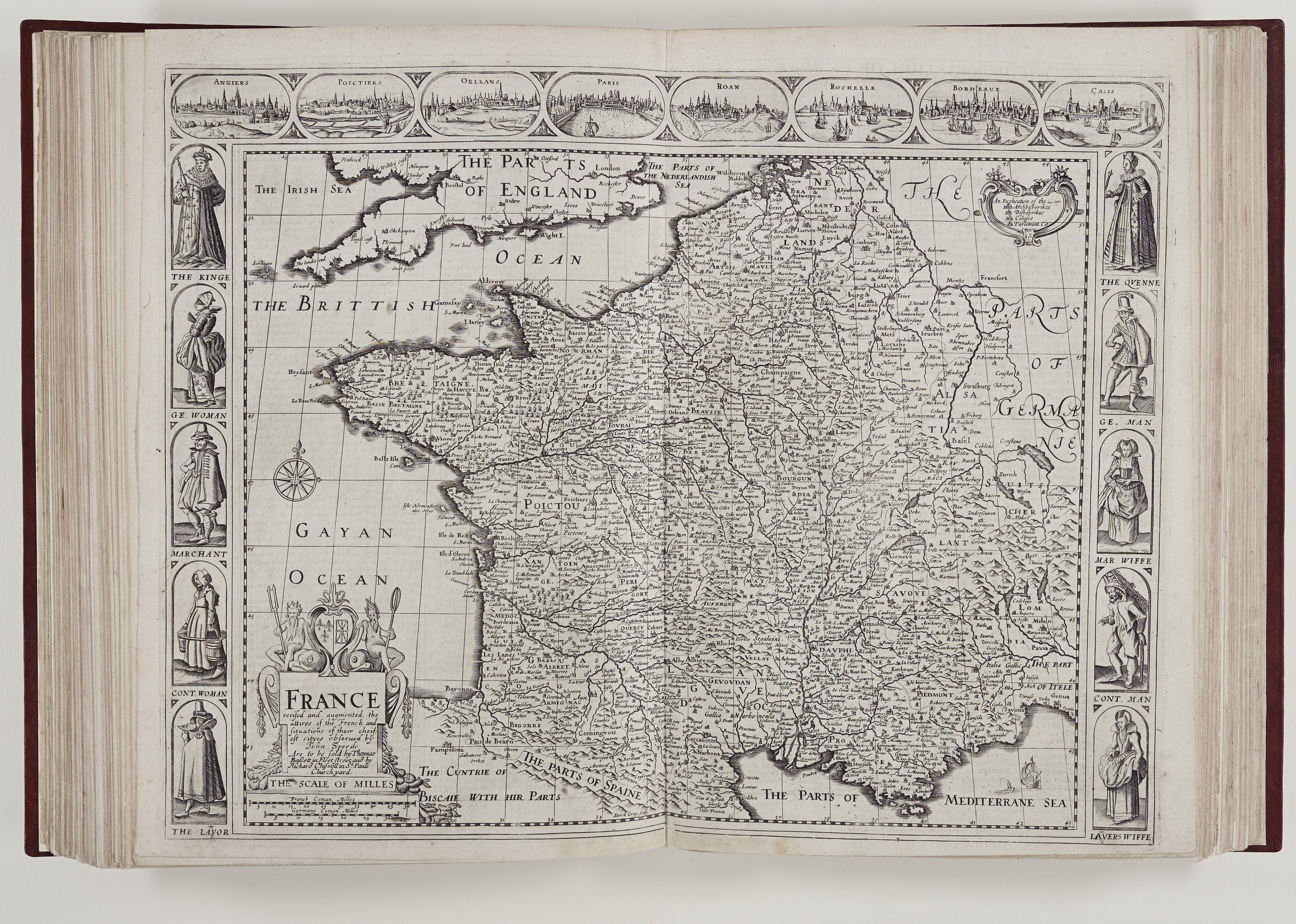

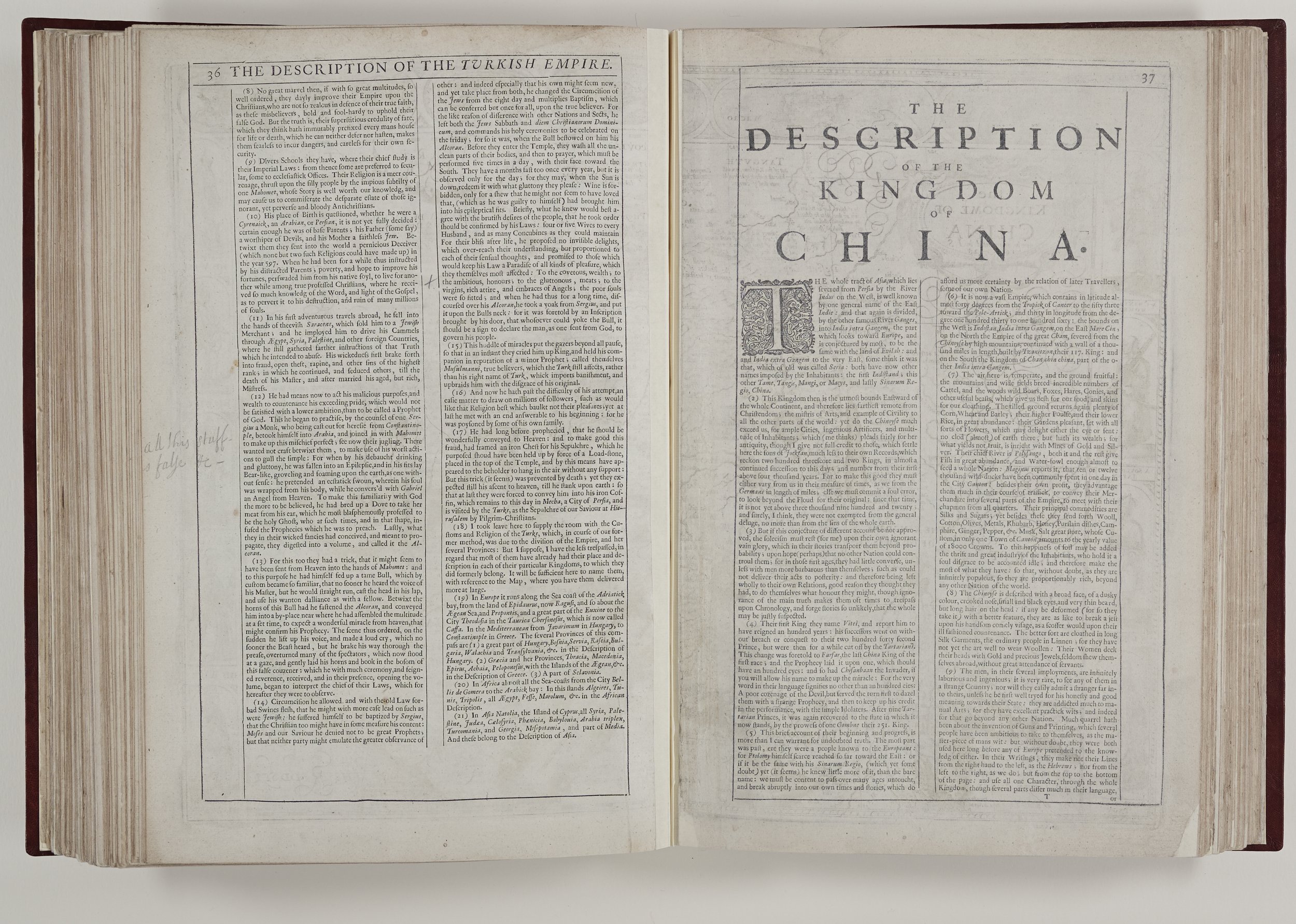

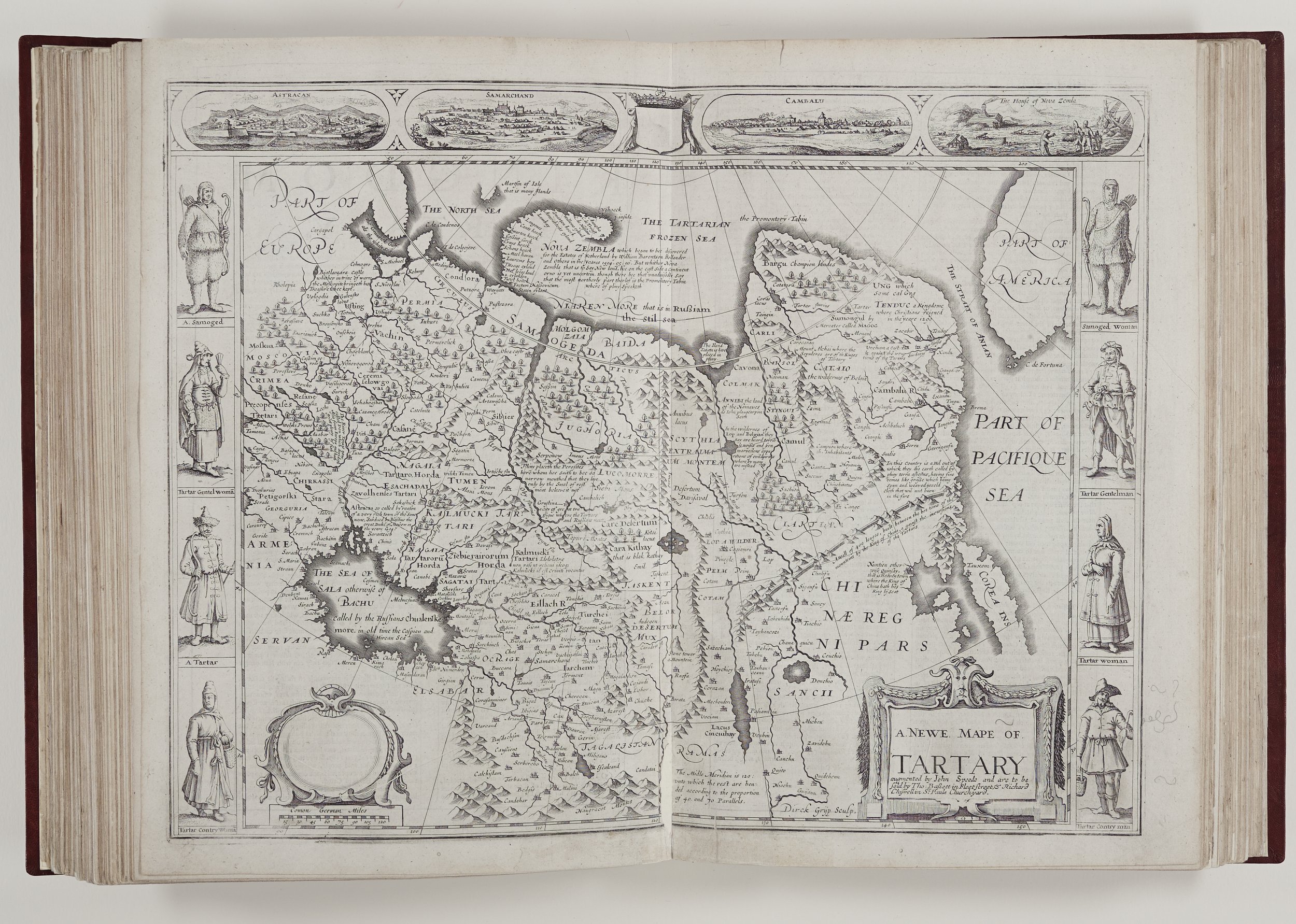

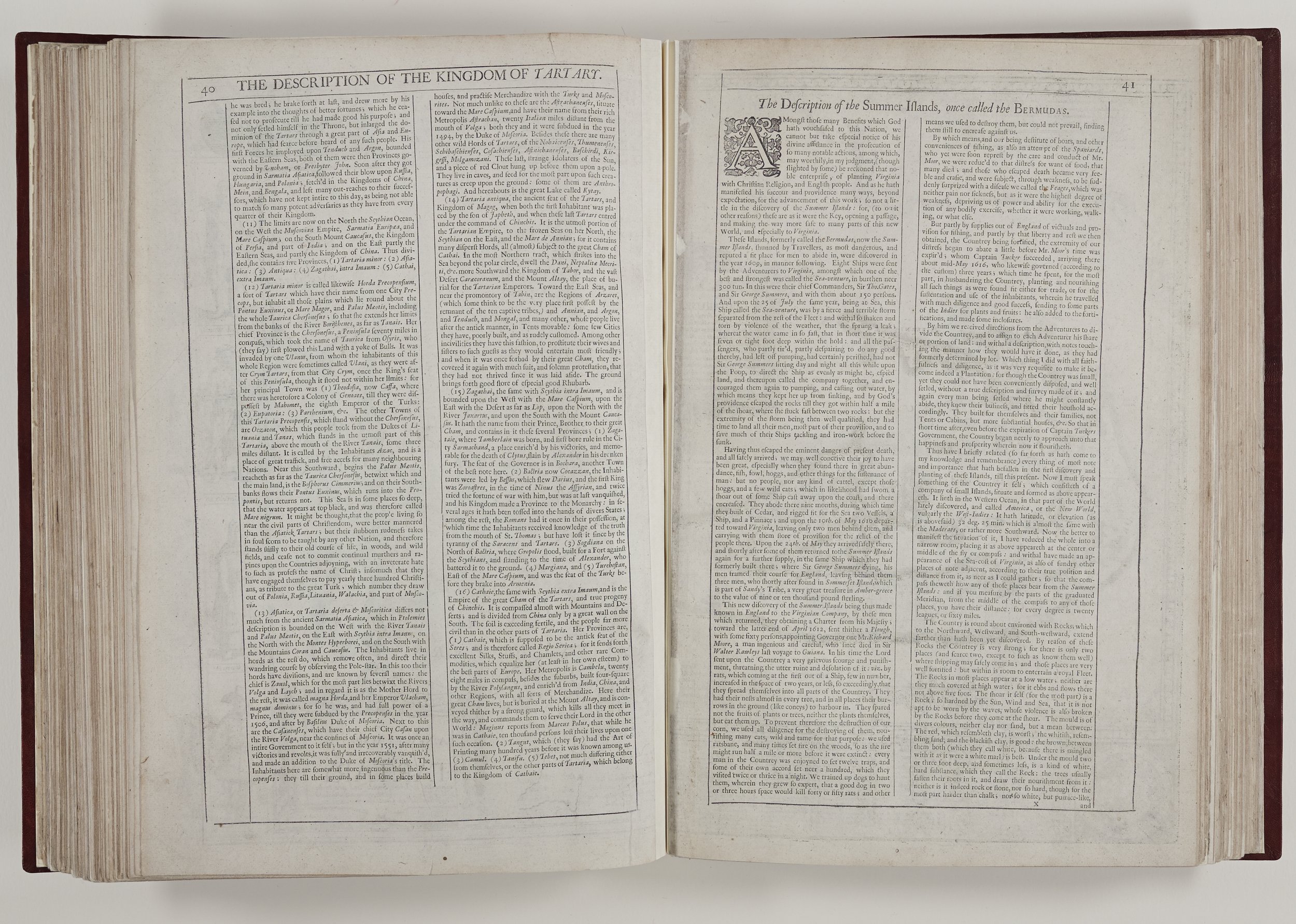

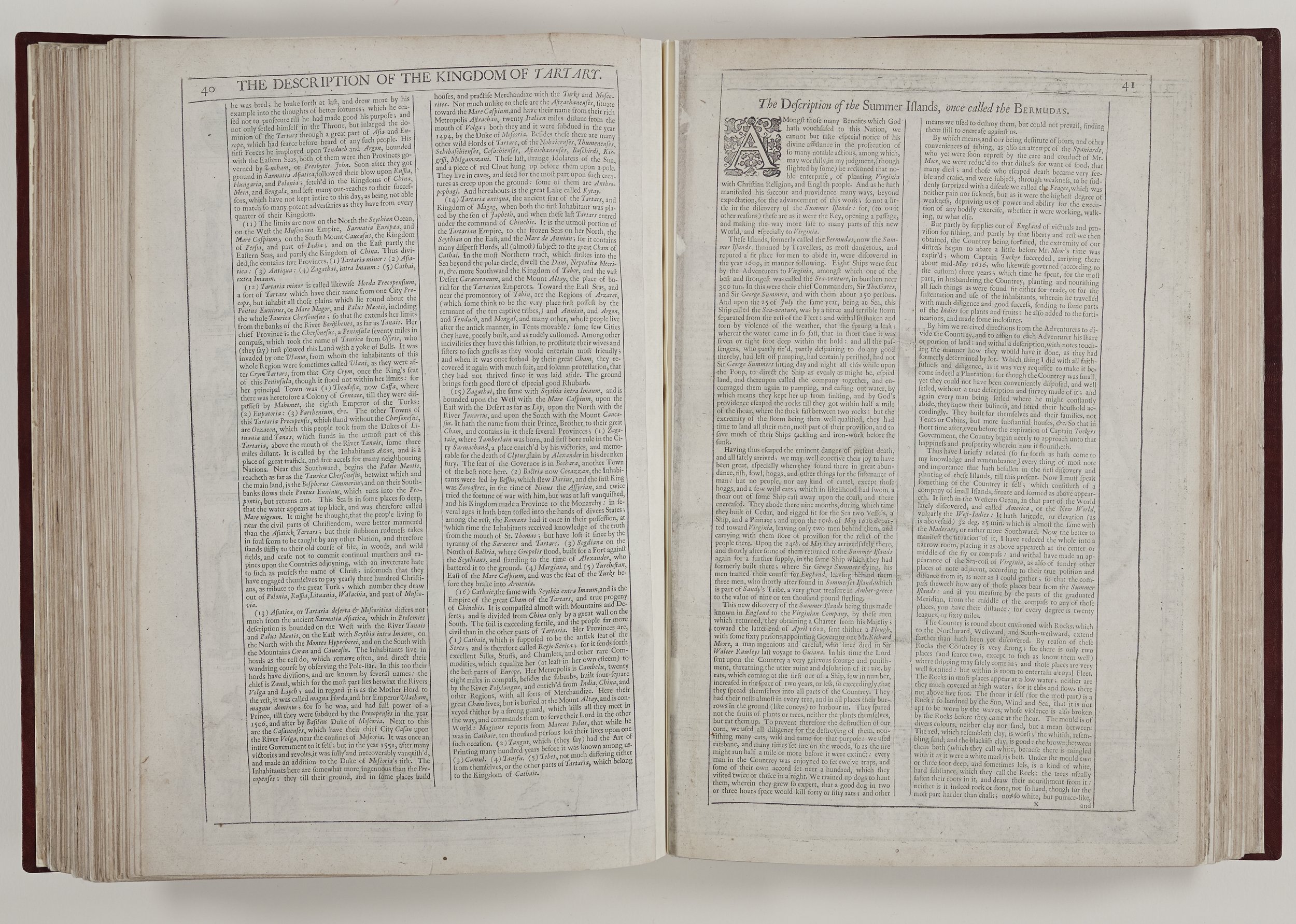

First published in 1627 by the London bookseller, George Humble, it was the first atlas to show an Englishman, John Speed, as the compiler, although the maps were engraved originally in Amsterdam or Antwerp by Abraham Goos and other Dutch engravers. Speed’s contribution to The Prospect has been the subject of much debate. In his introduction to a 1960s edition of The Prospect, R. A. Skeltern wrote that Speed probably had prepared some of the text but he relied heavily on early editions of Peter Heylyn’s Microcosmus and, as is evident to the reader, they sometimes lack the engaging style of Speed’s Theatre descriptions. Another striking fact is Speed’s own admission in a letter dated 13th April, 1626 that he was at this juncture, virtually blind. At this point he was revising his History of Great Britain, which he regarded as his major work and was requesting help. As Skeltern says “This hardly suggests capacity for the exacting task of compiling a world atlas.”

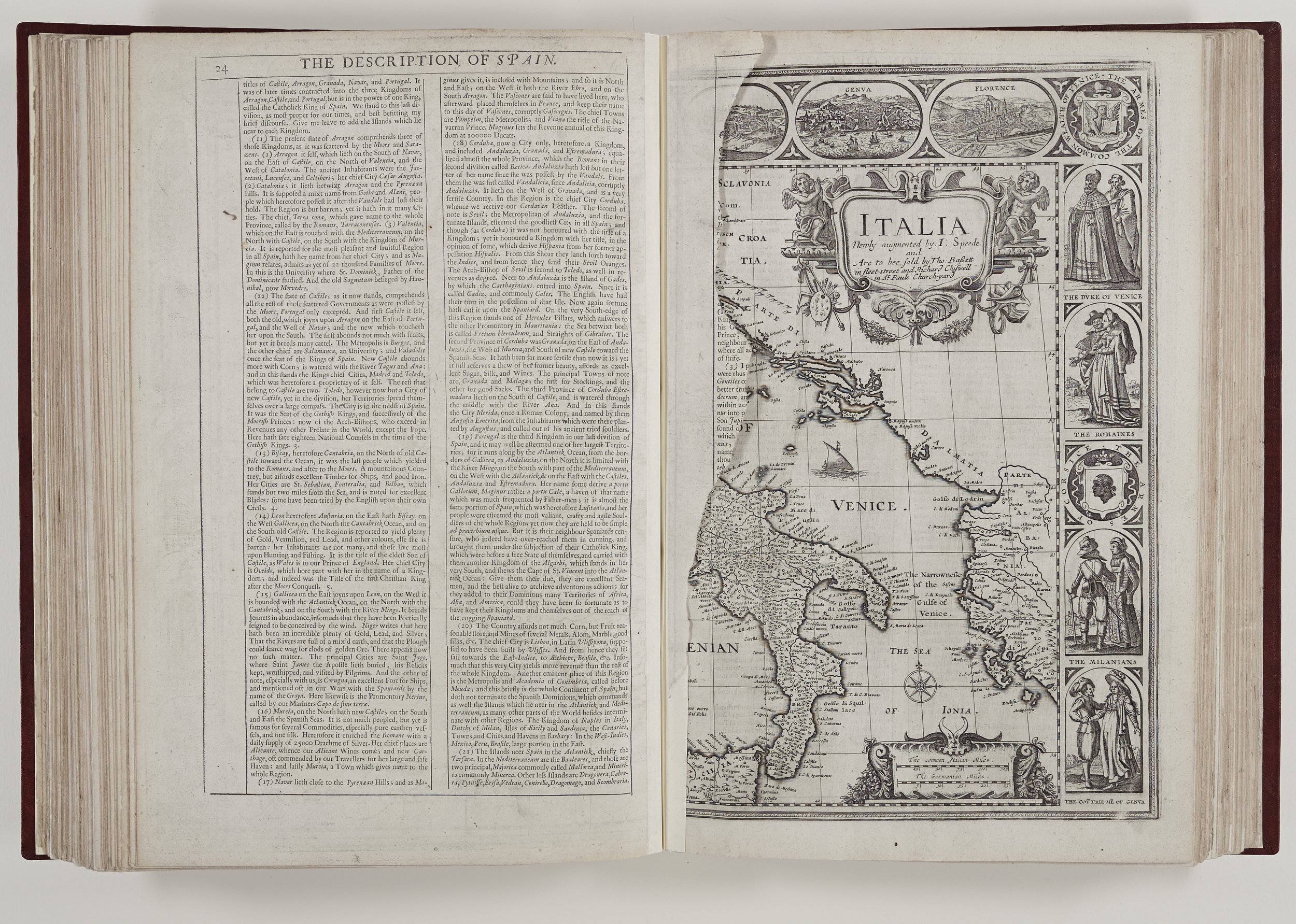

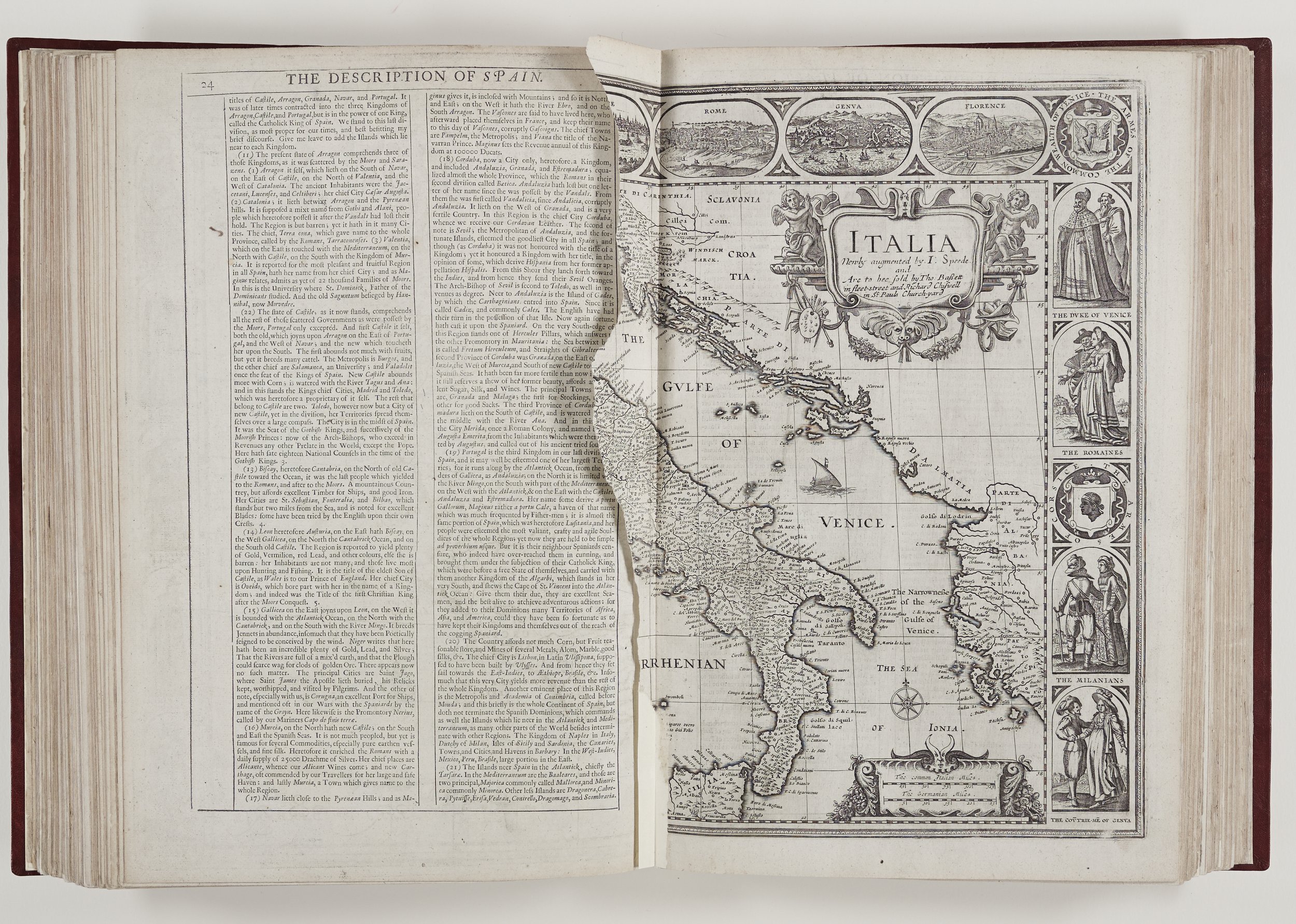

It is very likely that Humble saw the huge commercial possibilities of this venture and wanted to prosper from the flourishing interest in world maps. There are no customary commendatory addresses here and little of the organisation to be found in The Theatre. Many of the maps were outdated, some by the 1620s and others by 1676. Some maps and text are missing from the Rochester edition and in the case of northern Italy, torn crudely from the volume.

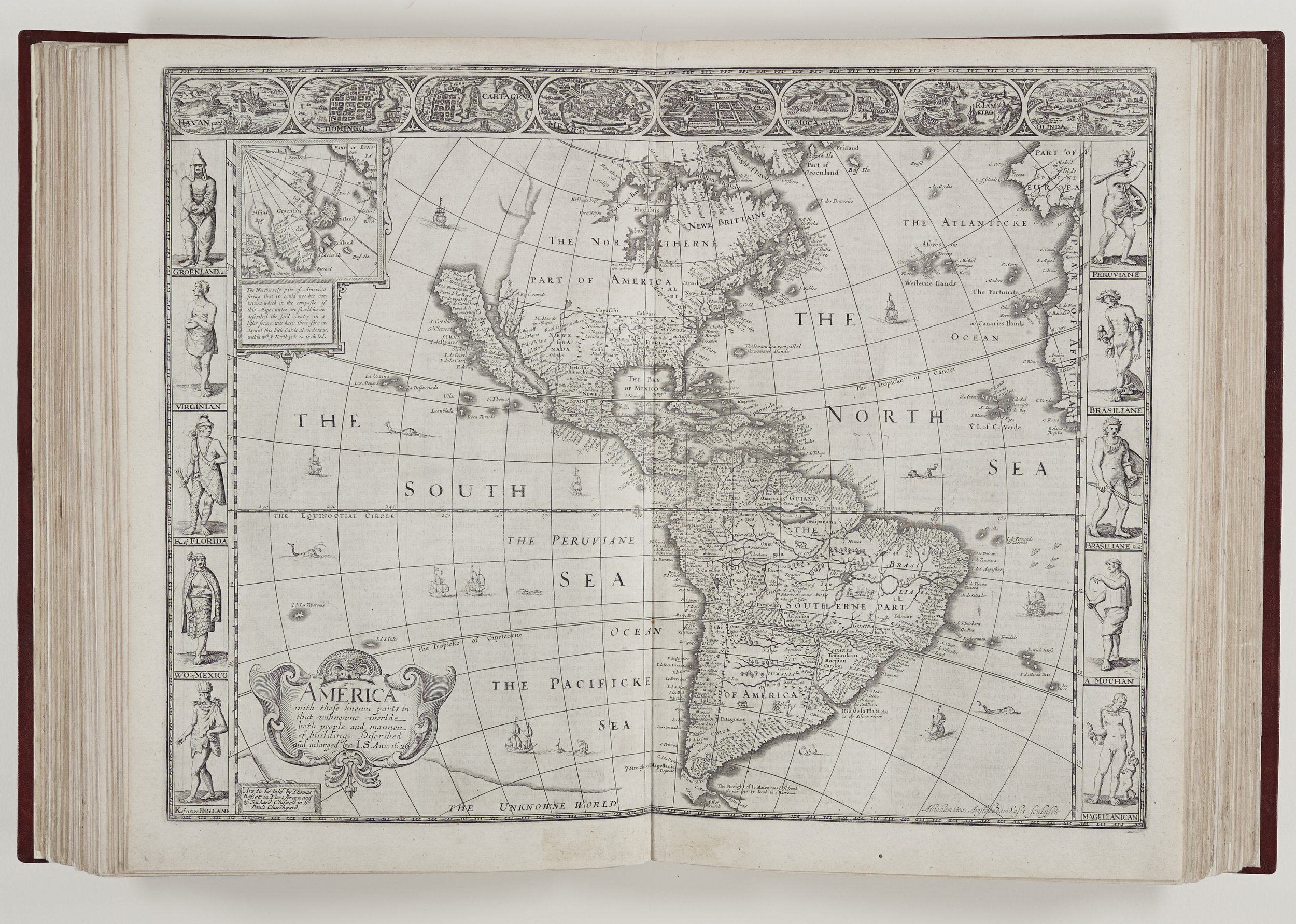

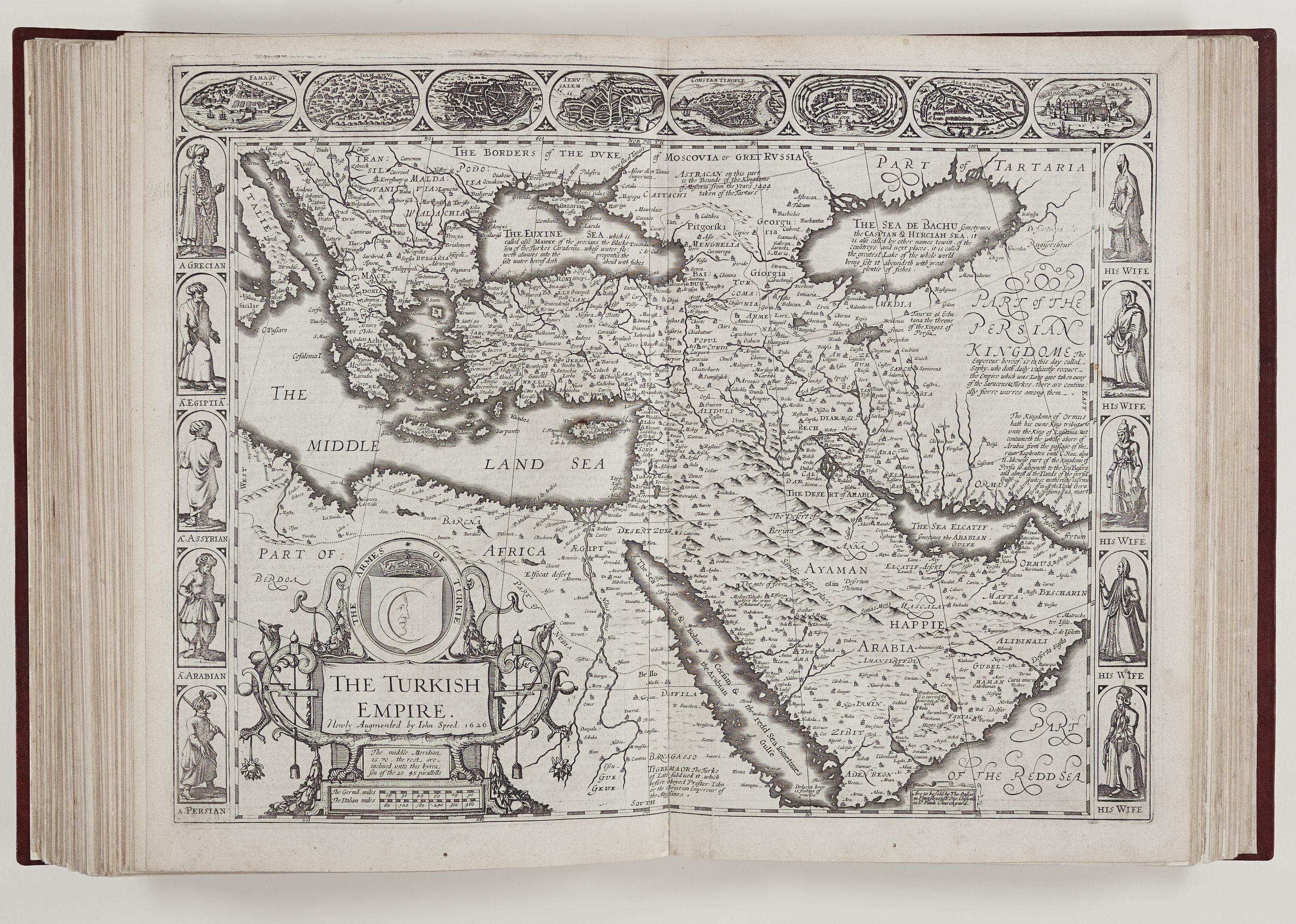

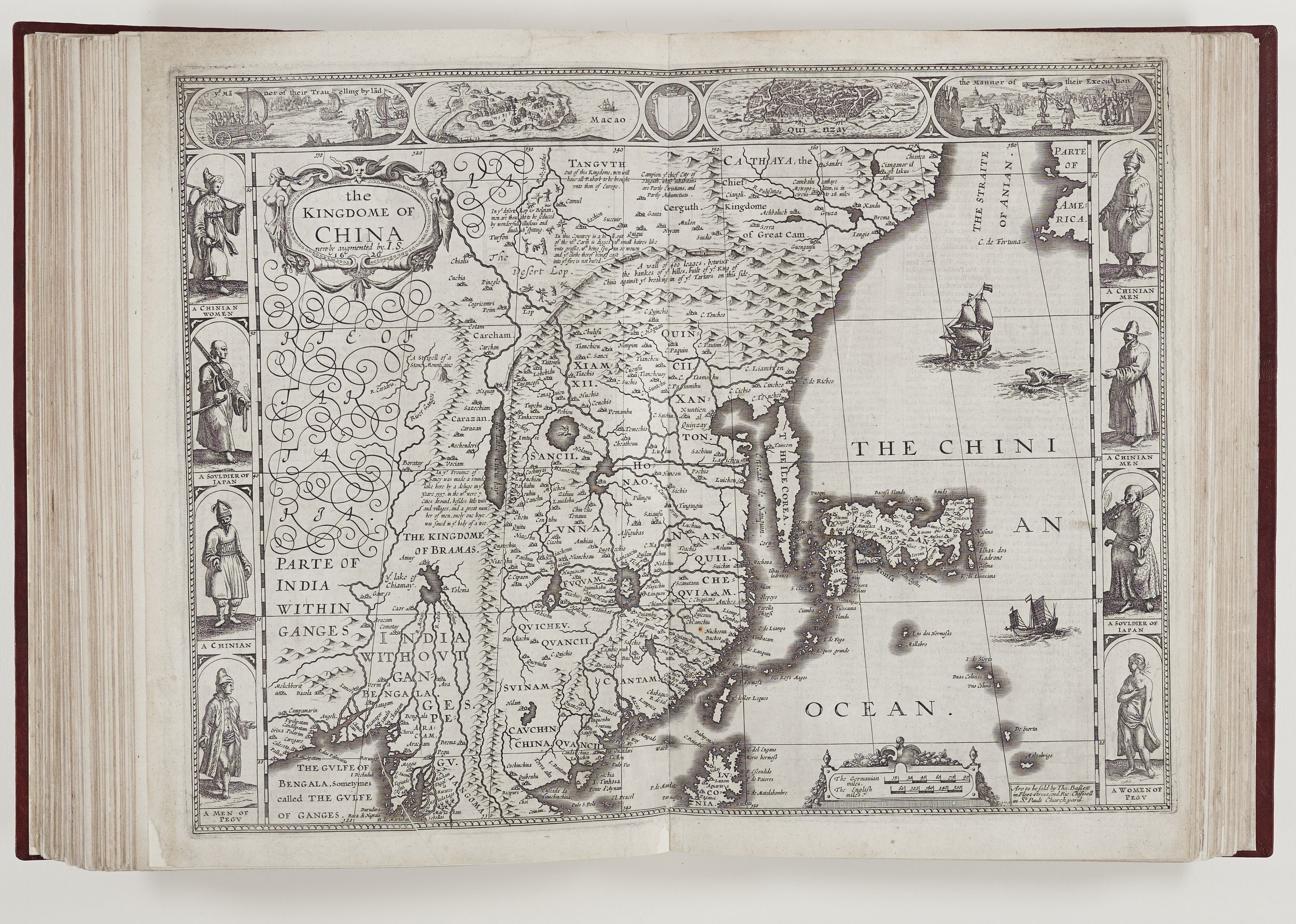

One distinguishing feature of The Prospect maps was the inclusion of costumed figures at the side of some of the maps. This was an addition by the Dutch engravers such as Blaeu but presumably one which Speed would have endorsed given his predilection for decorated borders, including people. Although by the early seventeenth century global exploration and trade would have furnished the engravers with some information, the figures are probably the result of a little knowledge and a great deal of imagination. The European countries show figures dressed in slightly differing versions of late Jacobean fashion. Hats and head coverings are ubiquitous. Different occupations and social classes are shown and the borders often include wives. Figures from the southern hemisphere are often portrayed in less clothing and women from middle Eastern countries are shown without facial coverings. On the torn Italian map the figures are different as they appear in pairs. However, whether by accident or intention the form of the maps with their peopled borders, inserts and flourishes blends well with the map style of the earlier Theatre and gives a uniformity to the whole text.

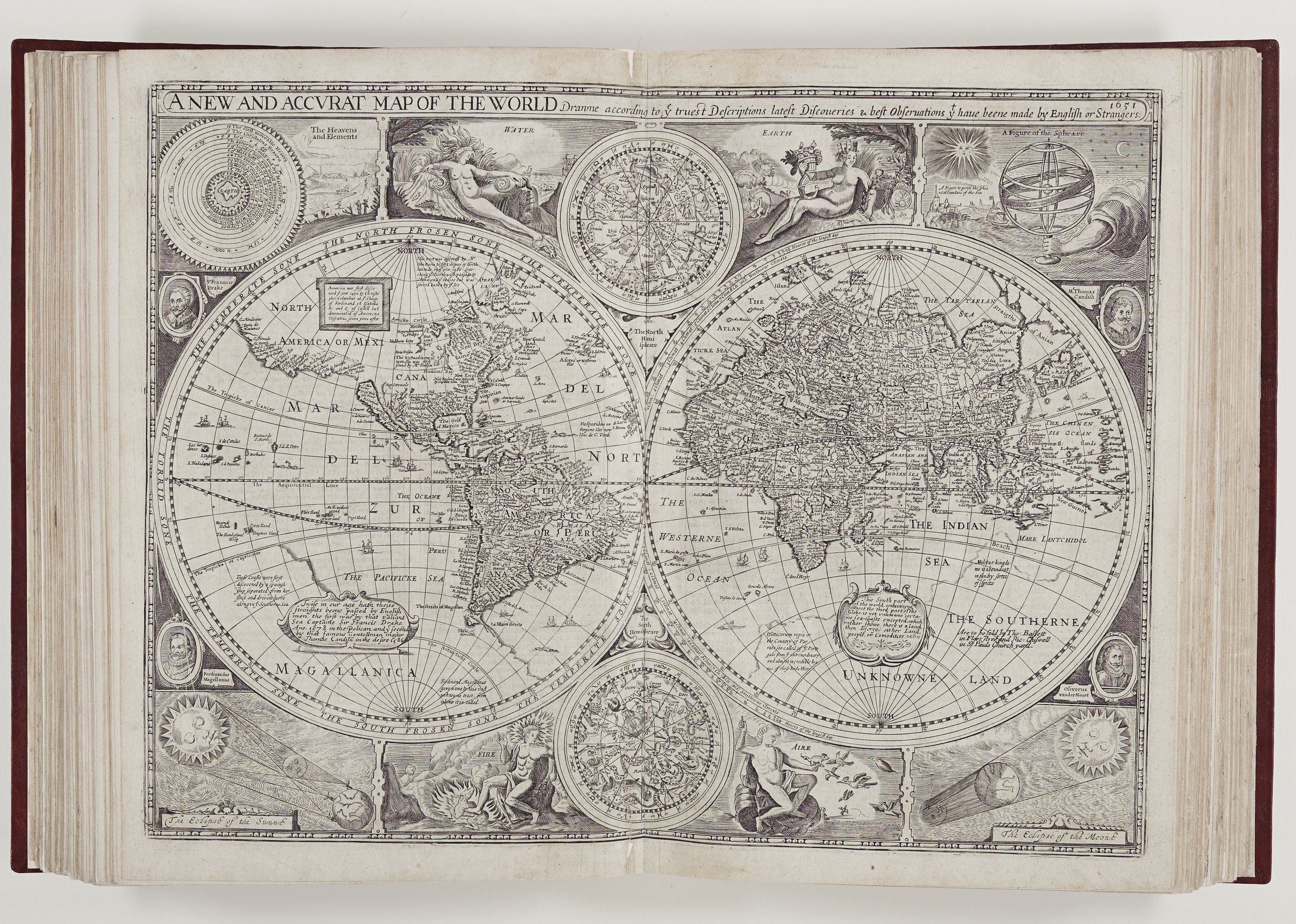

Visitors are often fascinated by the map of the world which bears a 1651 date. This map is interesting because it perpetuates an error which was constantly repeated until the mid-eighteenth century. It depicts California as an island, although as early as the 1590s it had been shown to be a peninsula by Mercator, Ortelius and Corneille Wytfliet. In the accompanying text we are told Baja California is perhaps the biggest island in the world bordered in part by the splendidly named Vermillion Sea.

British Empire dominions

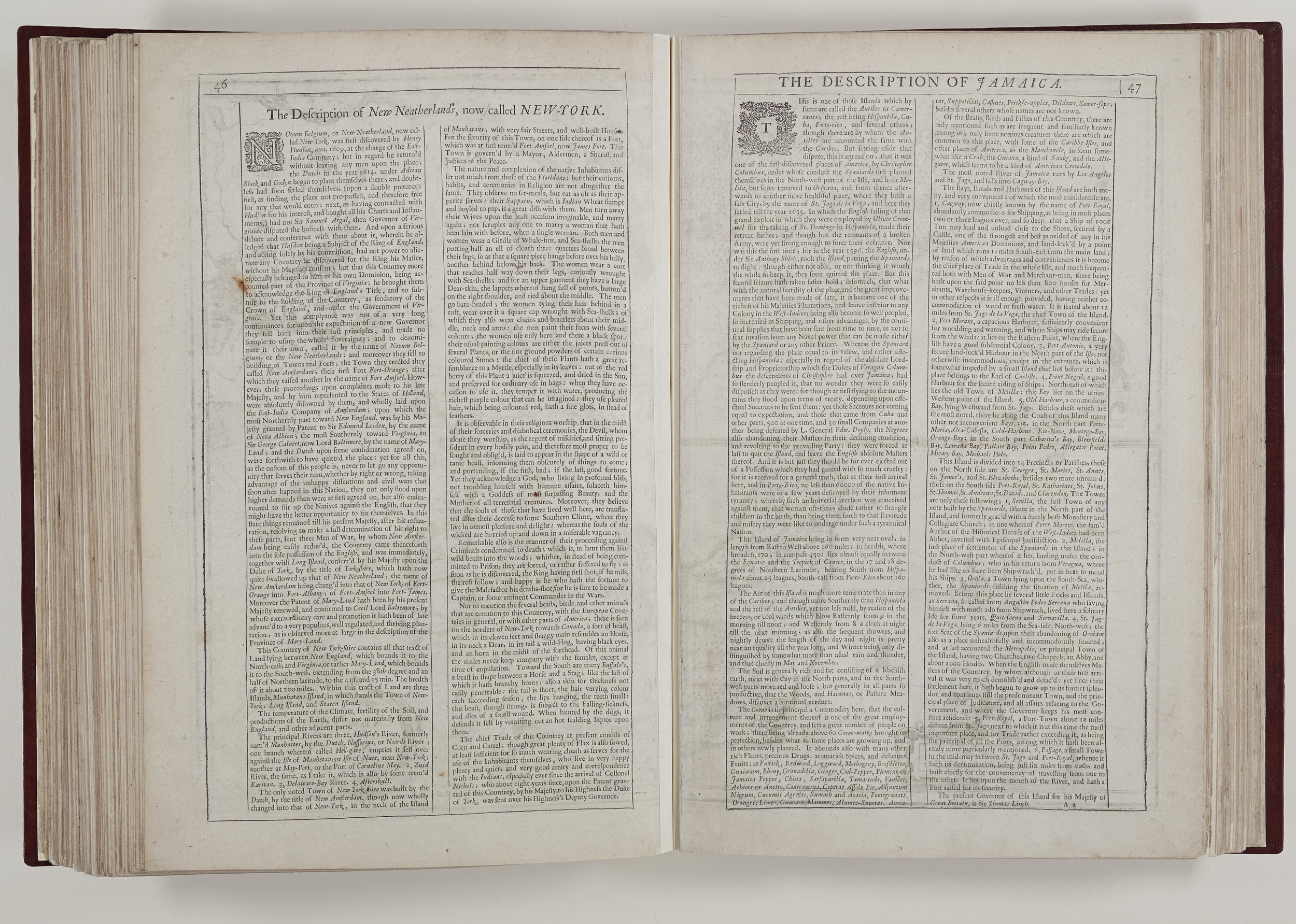

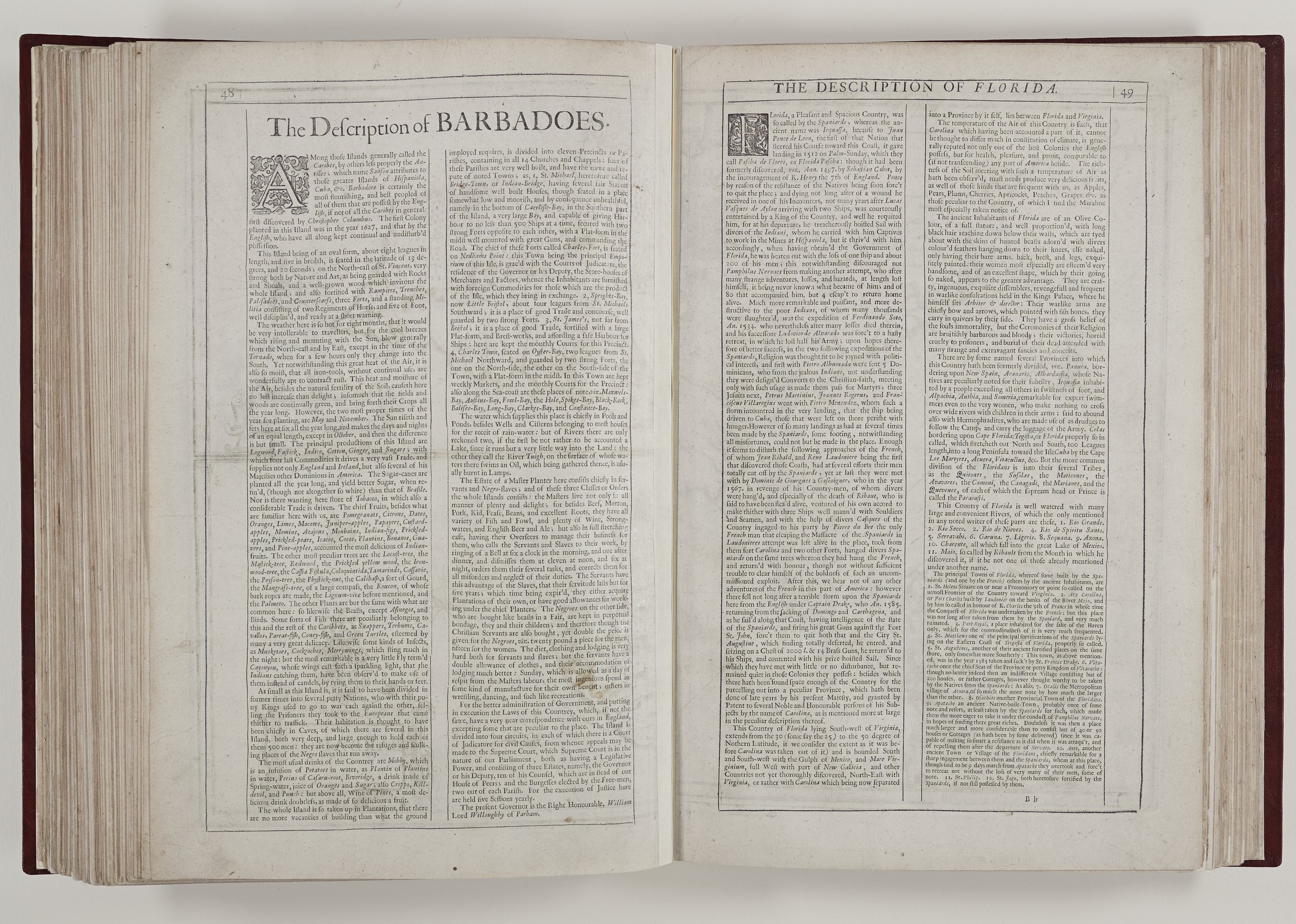

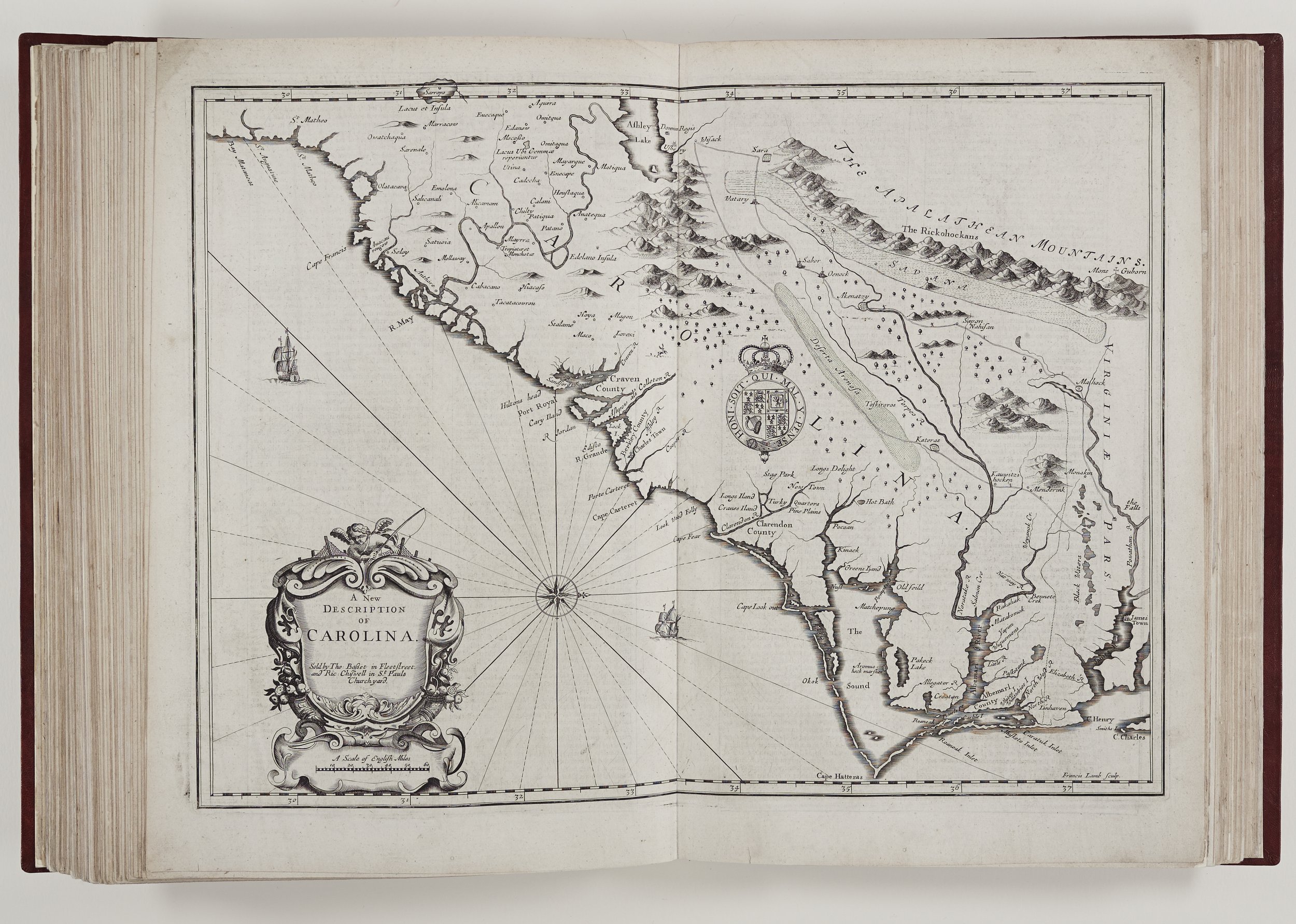

The most topical maps in this edition are the America maps of New England and New York, Virginia and Maryland, Carolina, Jamaica and Barbados. There is a description of Florida but sadly, the promised map from The Prospect title page is missing in the Rochester edition. The usual form of North-up maps is subverted in the maps of Carolina, Virginia and Maryland and there is a definite shift in style with these latter Prospect maps. The borders are less flamboyant and without the figures illustrating different races and costumes.

John Speed died on the 28th July, 1629 at the age of seventy-seven and his funeral was held at St. Giles Cripplegate where a monument, still extant, was erected in his honour. His descendants lived in Moorfields, London, Oxford and Southampton.

The 1676 edition was the last octavo edition and although the Prospect maps were generally too outmoded, Speed’s Theatre maps were revised, reworked and republished well into the mid-eighteenth century. John Speed’s reputation was secure and copies of his work are still highly sought and admired globally. It is a privilege to browse the Chapter Library edition, to see the world through the eyes of those with an earlier perspective and to hear John Speed’s inimitable voice.

Myra Amor

Library Volunteer

Bibliography

The Counties of Britain – A Tudor Atlas by John Speed N. Nicholson & A. Hawkyard (Pavilion 1988)

Speed, John (1551/2 – 1629) Sarah Bendall htttps://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/26093 (03 January 2008)

R. A. Skelton, introduction in J. Speed A prospect of the most famous parts of the World. facs. edn (1966)

R. A. Skelton, ‘Tudor town plans in John Speed’s Theatre”, Archaeological Journal. 108 109 -120 (1951)

W. Pettigrew, ‘Freedom’s Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752’ (2016)