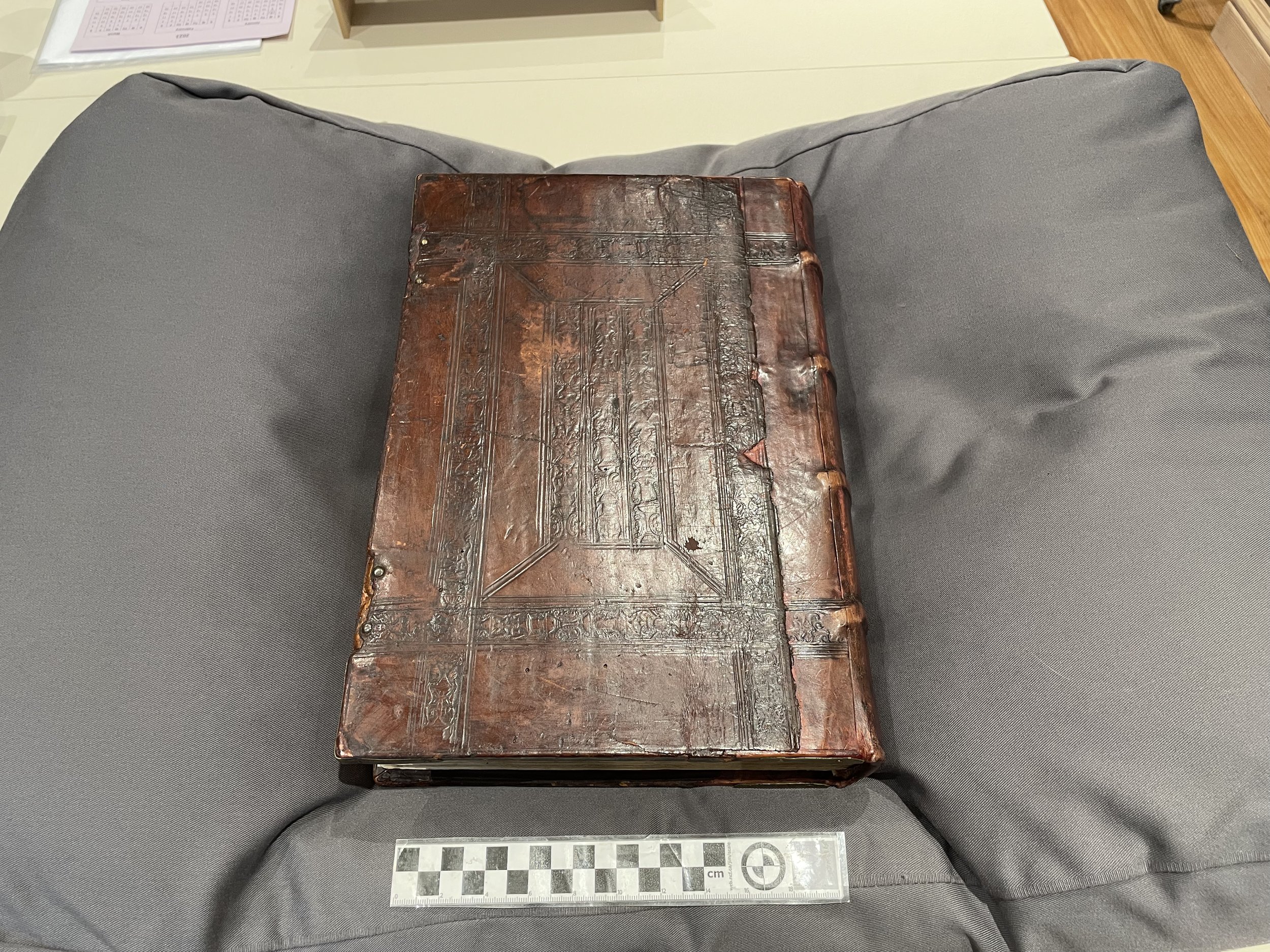

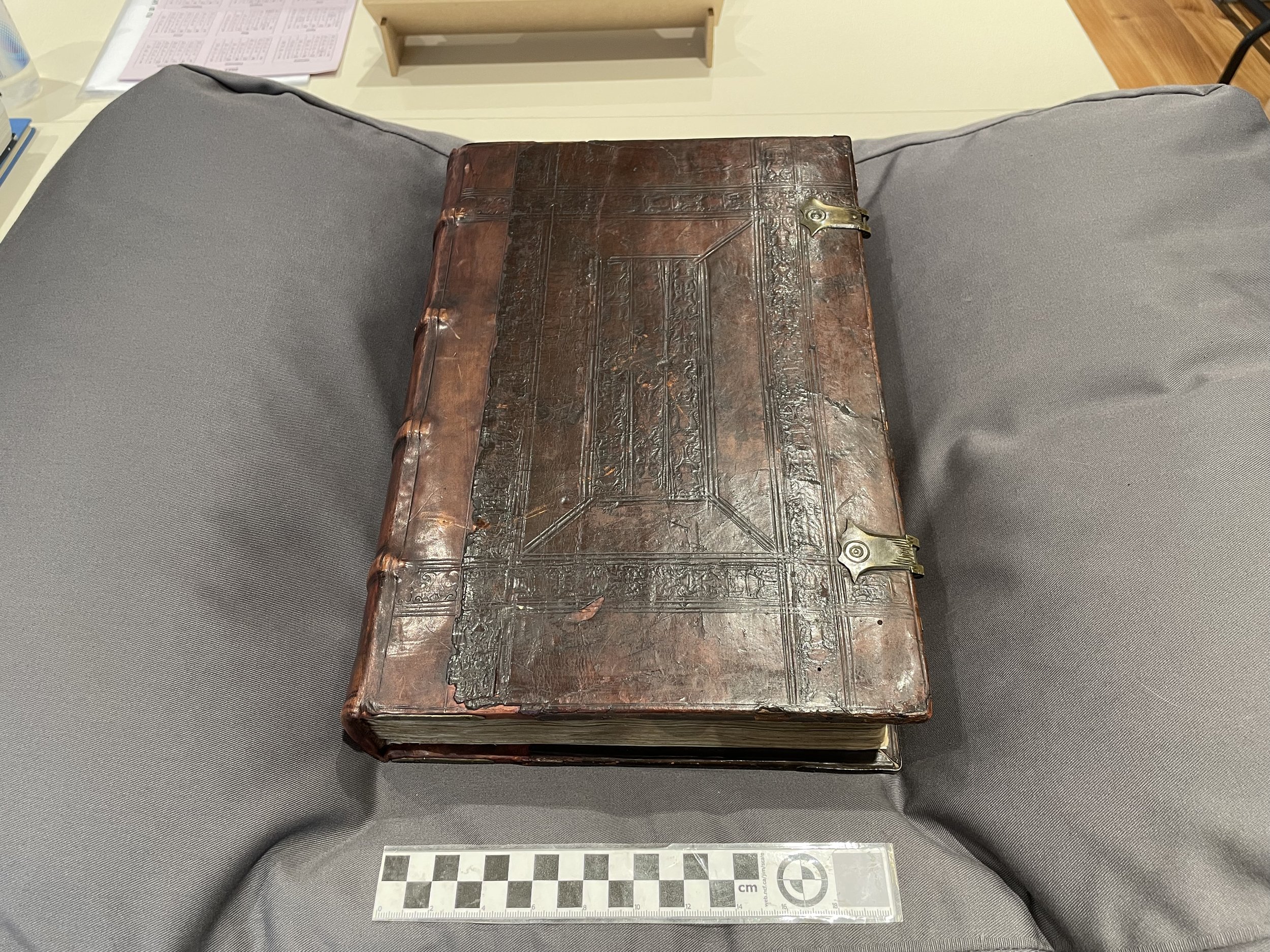

Sarum Missal, 16th century

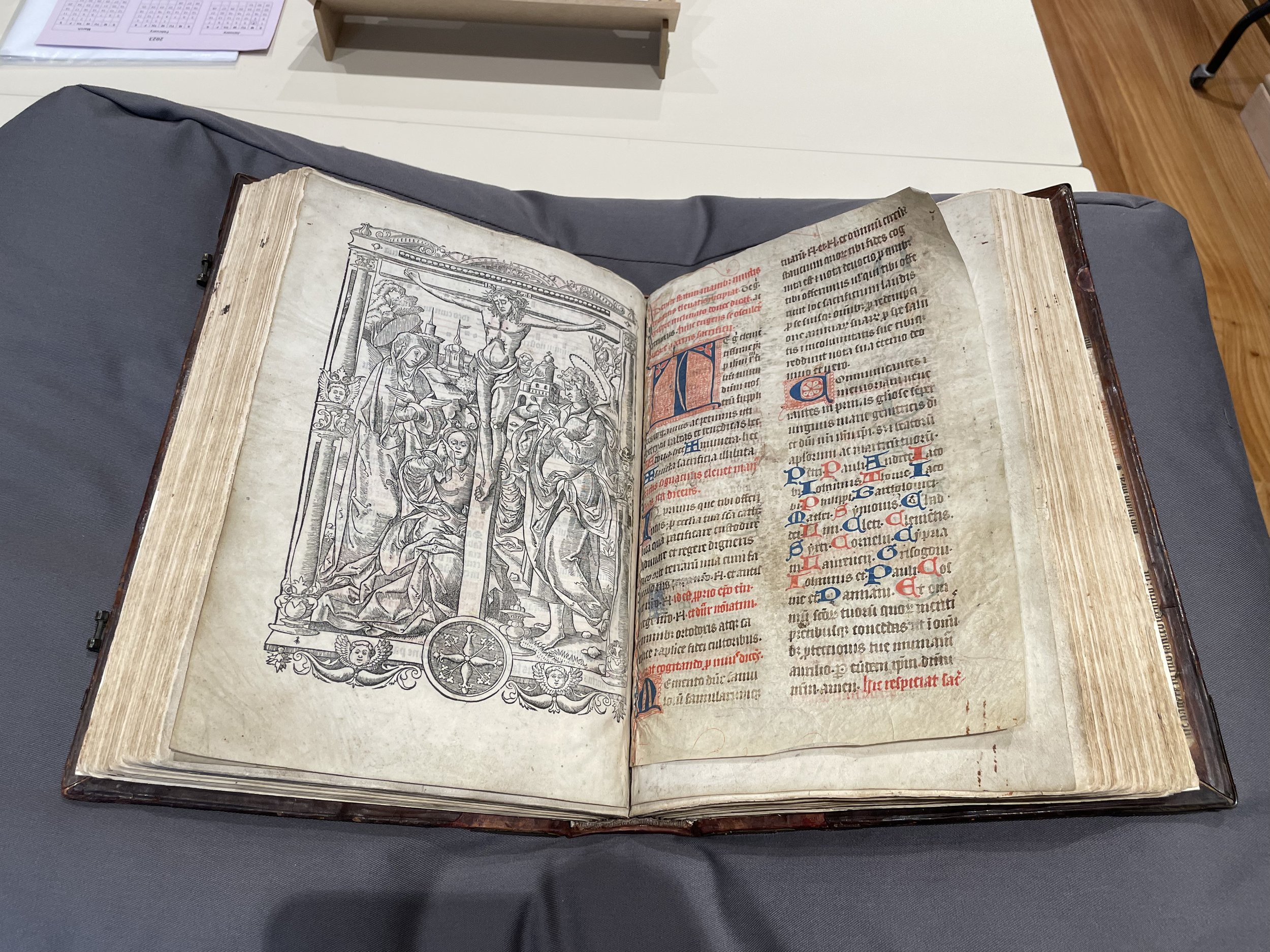

/Chapter Library volunteer Beverley Dee Jacobs leafs through the 16th-century Sarum Missal, a remnant from the final years of the Priory Library.

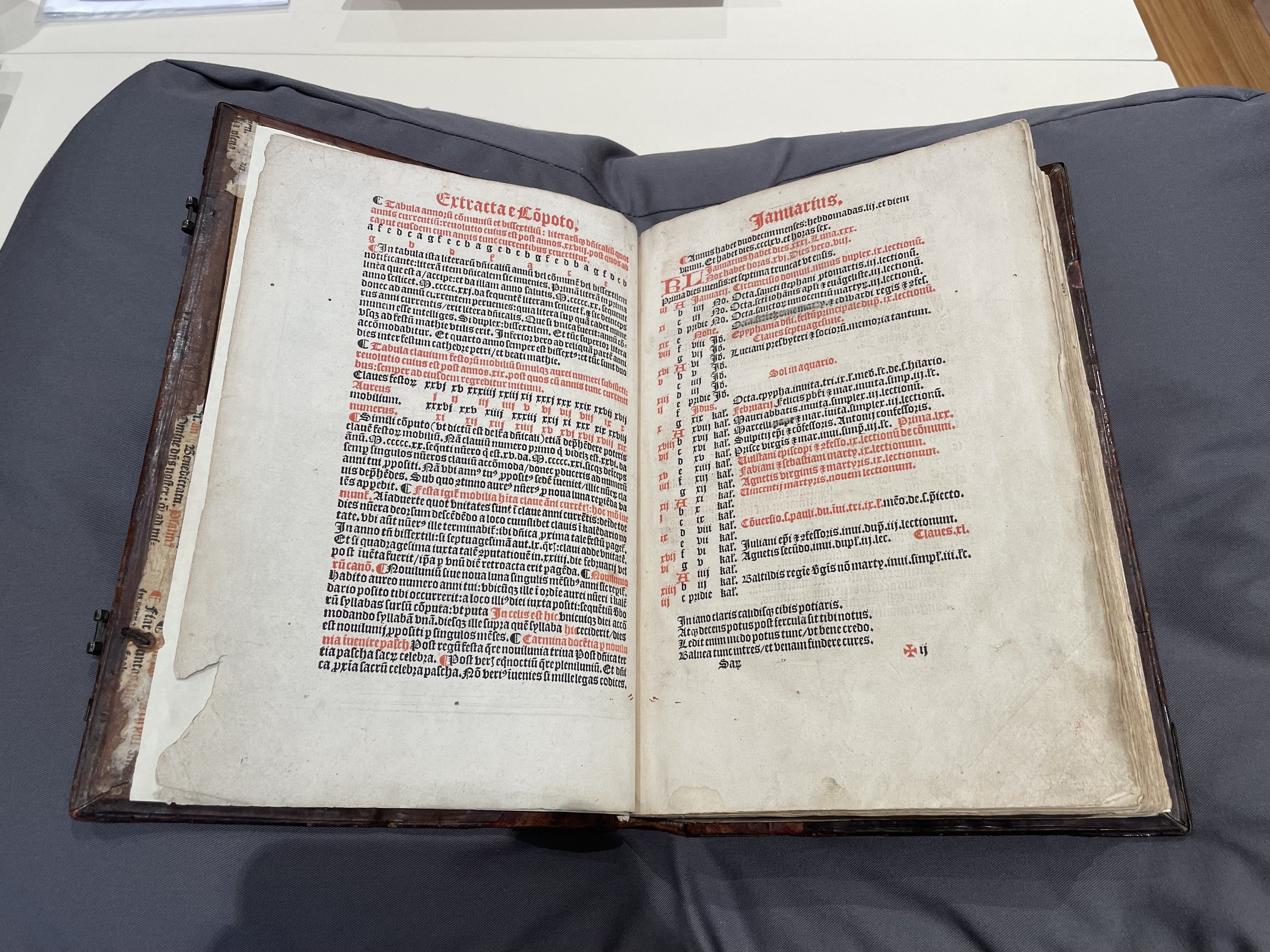

The Sarum Missal is one of the remaining pre-Reformation books in the Chapter Library of the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary in Rochester.1 It is dated 1534, is printed on good quality paper, but with the addition of several leaves of velum; one skilfully block printed and a further single leaf handwritten and delicately decorated. Whilst paper was gradually in more frequent used by this date it was expensive so the use of velum and parchment provided cheaper alternatives for printing. The velum leaves in the Missal, however, appear to be from an earlier manuscript but sadly there is no indication of their origins.

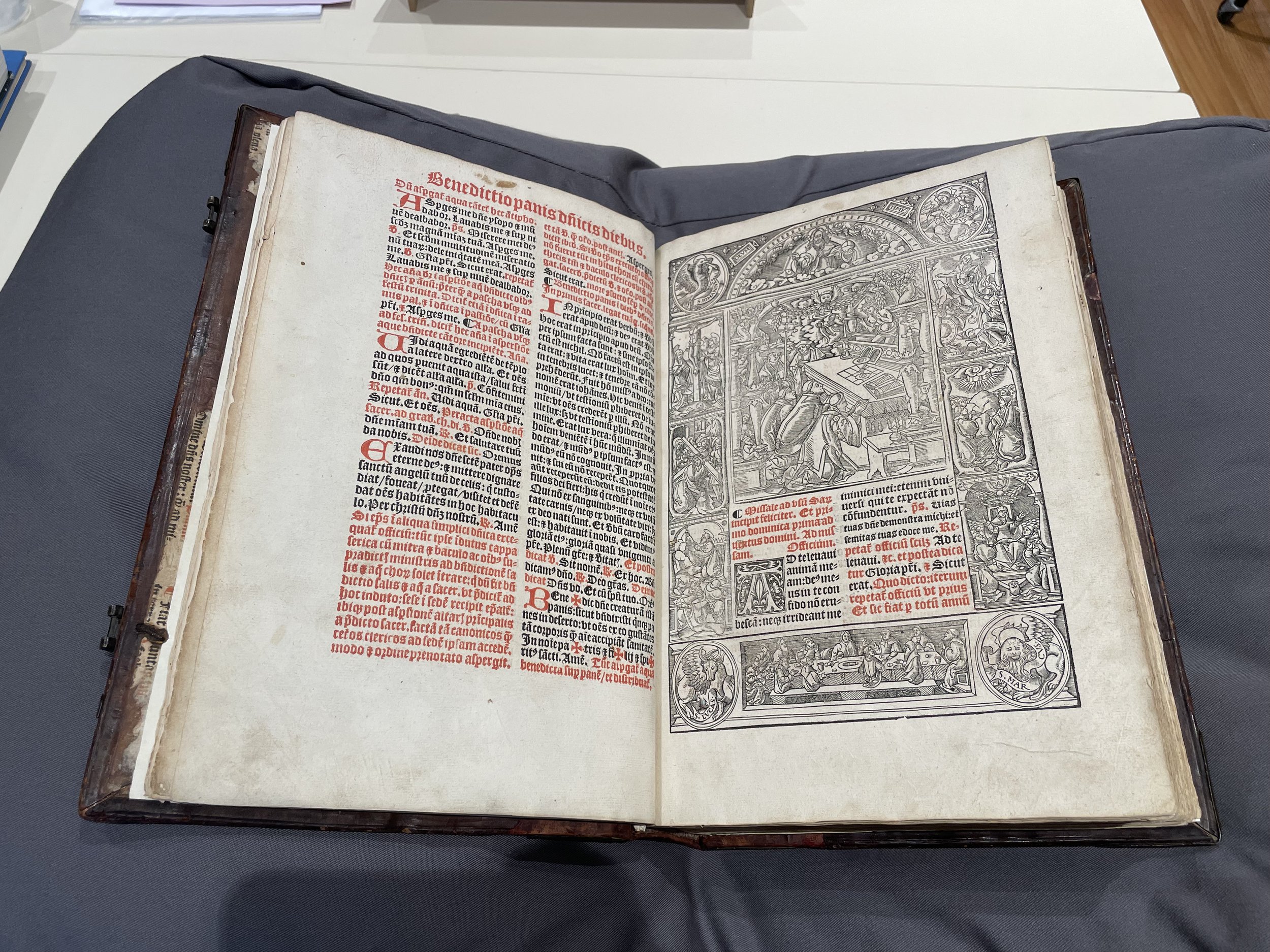

The frontispiece above shows the Tympanum of Christ in Majesty flanked by the Eagle of St. Johannes, the winged Man of St. Mattheus. Scenes from the life of Christ are shown on the left and right sides of the page, with the winged Calf of St. Lukas and winged Lion of St. Mar[c] flanking the representation of the Last Supper (showing 11 apostles) at the base. The symbolic coat of alms of King Henry VIII and the Tudor Rose form the main part of the centre of the page with St. George killing the dragon. Below the Tympanum it states in red:

C Missale ad blum ecclesie Saresburiensis M.D.xxxiiii.

Almost too faint to read in the top margin is a hand written form of Ex-Libris:

Eccl Cathedr Roffi Liber N.1

which surely indicates the continuing importance of this traditional service book in the church even at the time the Reformation was progressing. Comparing the frontispiece of the Sarum of 1534, which acknowledges Henry VIII symbolically (as above), with the frontispiece of the Great Bible published five years later (1539), displaying a portrait of Henry surrounded by his Ministers/Courtiers/ Clergy and many others, indicates a significant strengthening of his assumption of Head of the Church of England following the Act of Supremacy in 1534. The formal break with Pope Clement VII and the Church of Rome, however, did not mean that Henry deserted his faith – he was always a Roman Catholic. The Church of England continued to use the Latin Liturgies until Edward VI came to the throne in 1547 so many Sarum service books were printed and still in use by that date. With the accession of Edward VI and his Injunction of 1549, all service books according to the Sarum Rite (including other adaptations in Hereford, York, Bangor and Lincoln) were to be defaced/destroyed: ‘utterly abolished, extinguished, and forbidden’.2

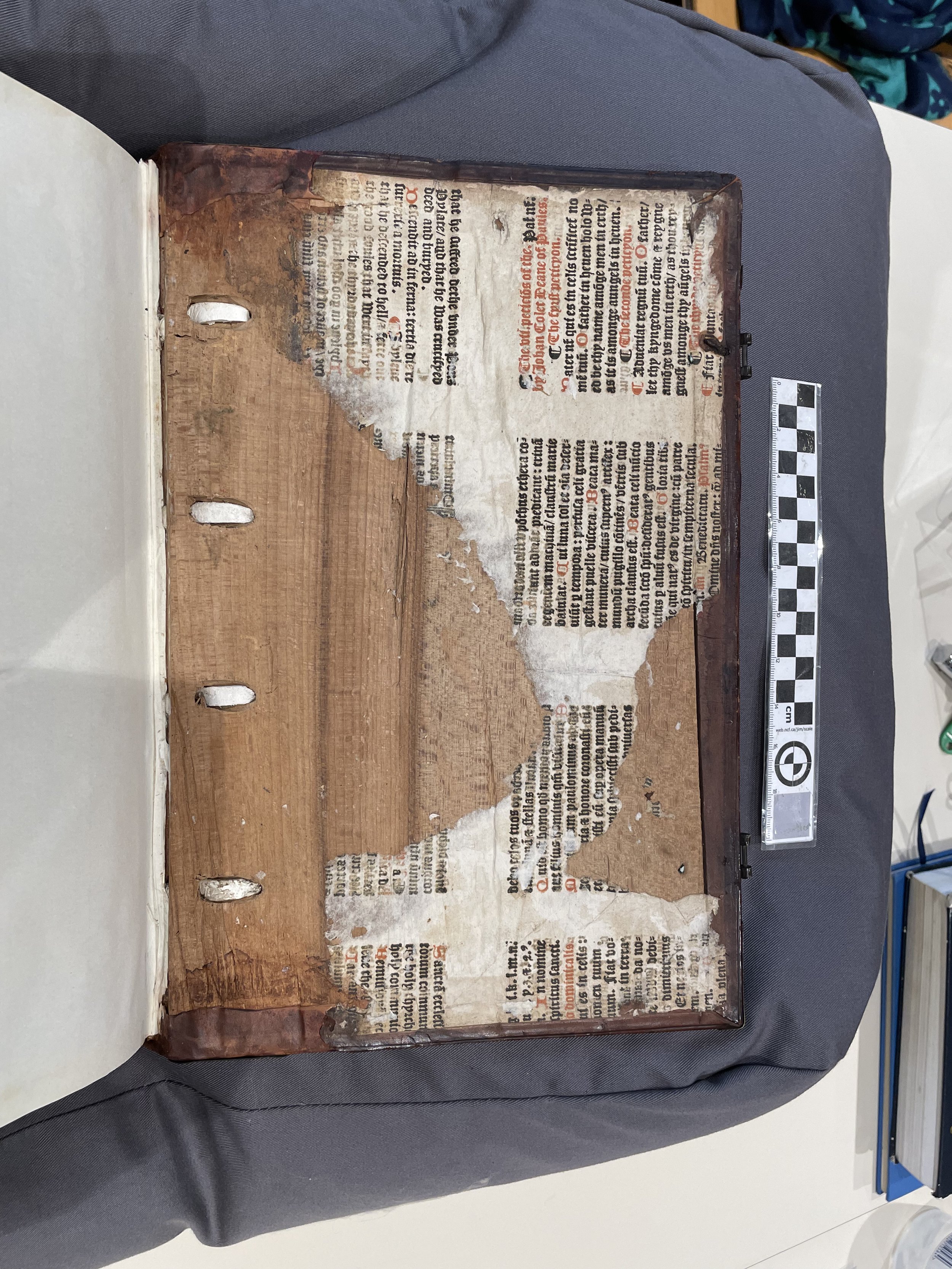

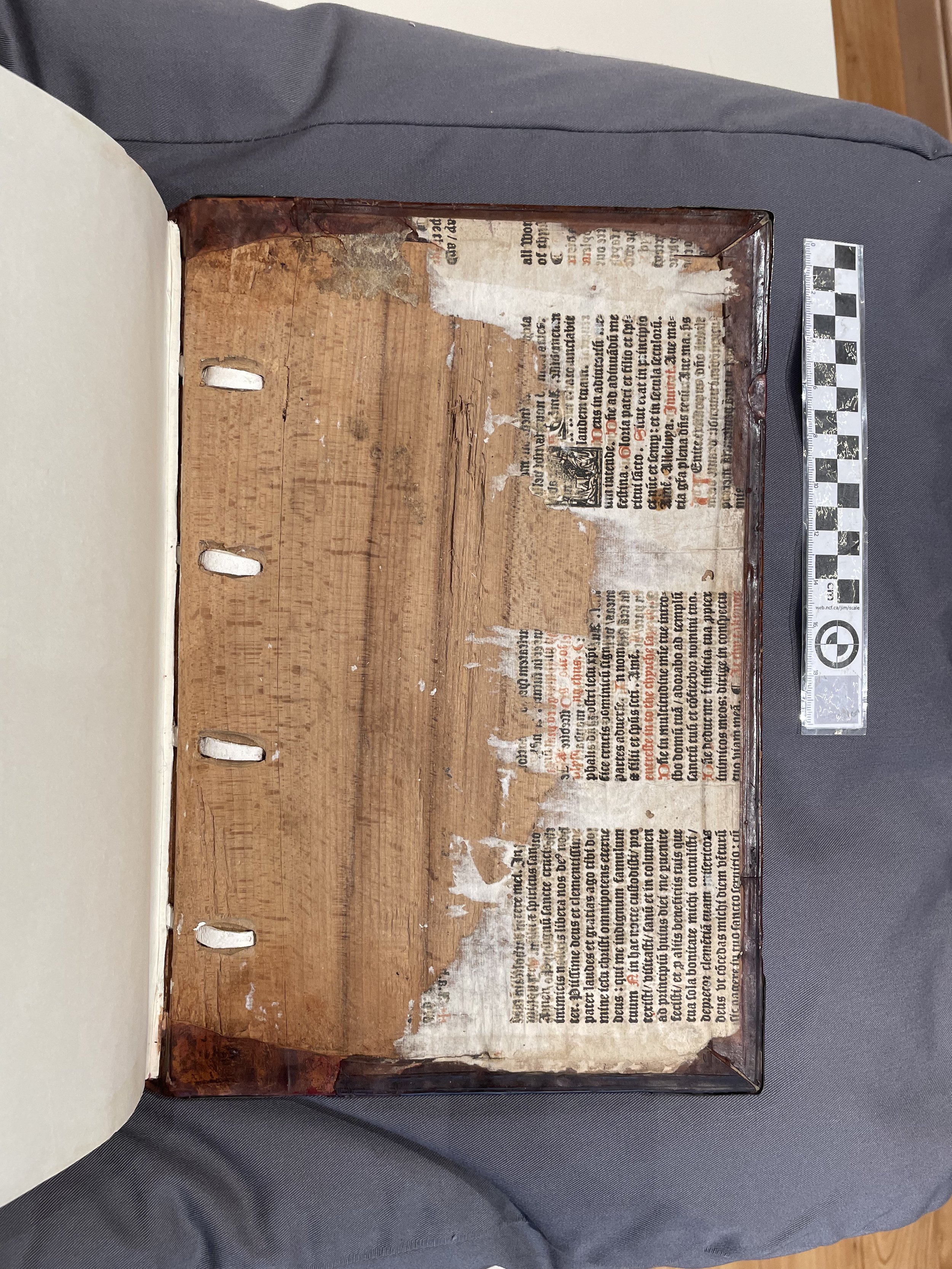

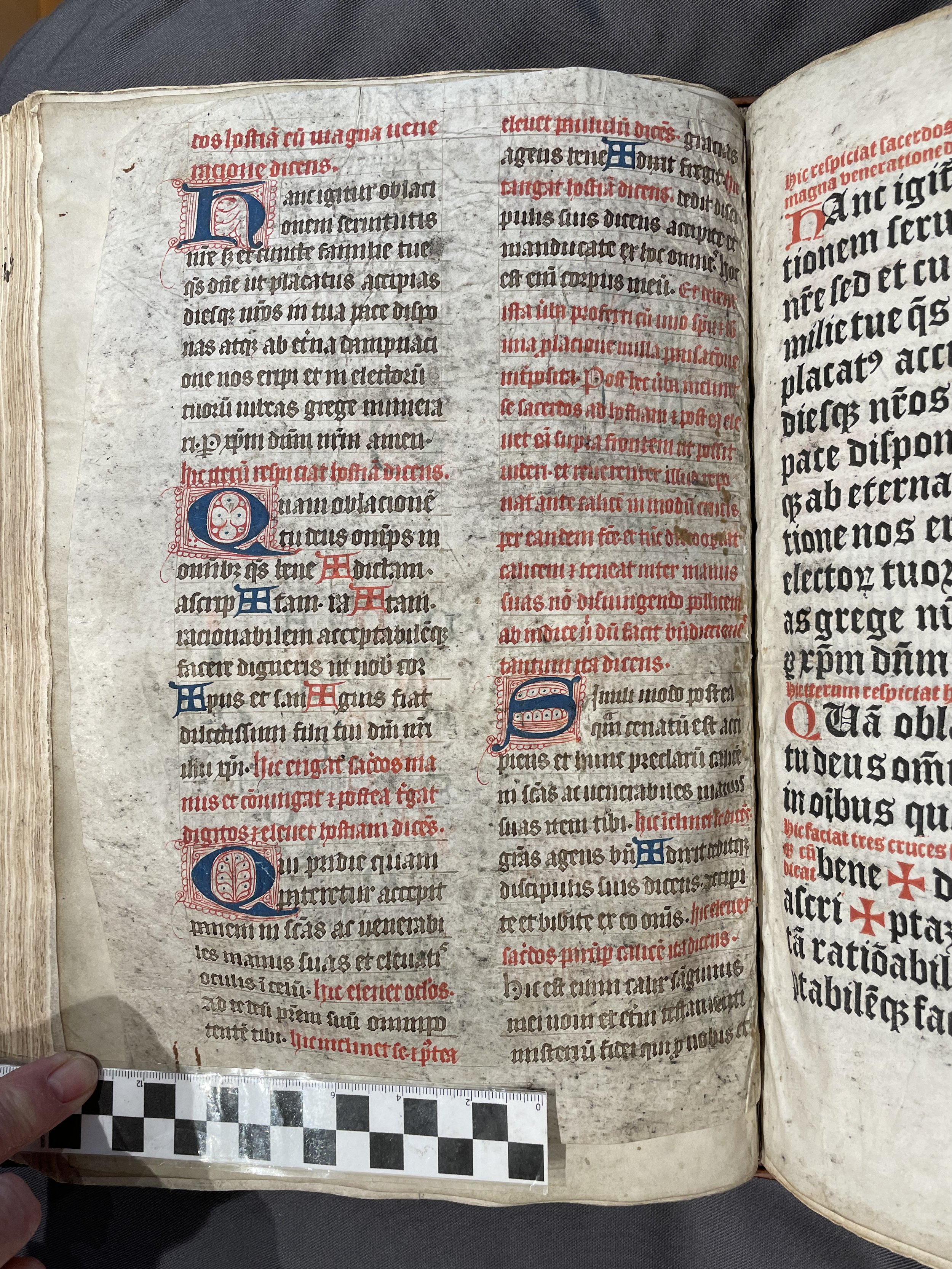

The printed Sarum Missal shown above measures W.24 cms. x L.35 cms. x D.7.4 cms. and contains in excess of 310 pages. It is a hefty single volume which consolidated all the individual service books once used before the Conquest. A study of the above has much to tell. The front and back binding boards have been re-used from a considerably older tome – perhaps carefully salvaged from a very early service manuscript. The tooled leather outer covers show the patina created by many hands touching it. The design, however, is no longer as crisp as it once was, but still shows the artist’s skill and its beauty. Remains of metal clasps are present on the leading edges of front and back covers. Though not complete they clearly indicate the value and importance of the manuscript they previously held safely closed. Within the interior of the old binding boards new wood has been cut to size to insert and strengthen the old binding. The printed paste downs inside front and back bindings have been scraped off and are very damaged. Reference to John Colet (d.1519) one of the early Humanists (friend of Erasmus, also near contemporary of St. Thomas Moore and St. John Fisher) can be read. Also the first line of the Lord’s Prayer in Latin. The spine is clearly considerably newer than the old boards with a gold blocked date on which it was printed/bound at the base i.e. 1534. At the top of the spine in gold is Missale. To provide strength for the old binding boards to be secured to the new spine metal strips have been attached with tiny flat headed nails. On each of the outer corners of the binding are metal protectors. Whatever was held between the original covers in the past was valuable, just as its present contents were (and not least for research, knowledge and understanding today)! It is clear that re-cycling was well-known long before our present times! The British Library owns a Sarum Missal manuscript that is believed to have belonged to Rochester Cathedral. It lacks a handwritten Ex-Libris but has been identified by the style of script favoured in Rochester Priory’s scriptorium.3 A Missal is not recorded in the Book List contained in Textus Roffensis (ff: 224r – 230v) dating to 1122, or the later Rochester Book List dating to 1202 enumerating the Mss. in the Priory’s collections at those dates. Service Books, however, were owned by the Cathedral church not the Priory. They would have been placed on the altar, close by it or possibly in a cupboard in the Cathedral.4 The Sarum Missal contains the yearly calendar of services for the Roman Catholic Liturgy. It has all the many services for the year from January through to December. Much discussion and debate has taken place about its origins and use in this country, but it was initially widely used in the south of England. First adaptations to facilitate its use, however, have been attributed to St. Osmund, the Norman nobleman appointed by William the Conqueror to be bishop of Old Sarum (Old Salisbury) sometime between 1077 – 1099. Inevitably, in modern times, this fact has been questioned by historians.5 Because of the Missal’s complexities in use, after Bishop Osmund’s simplifications, other bishops in England also followed his example by effecting their own adaptations/amendments. At the time the book was printed and bound, changes were taking place, not only in the British Isles but also in parts of Europe, which were going to affect the Roman Catholic church. Henry VIII’s Great Matter during the 1530s was the cause of significant organisational changes to aspects of religion and worship in future years in this country. Even as Henry VIII took on the role of Supreme Head of the Church of England and finally agreed to the publication of the Bible in English in 1539, the Sarum Missal was still in use and was so to the end of Henry’s life. With the accession of Edward VI in 1547, his Injunction in 1549 stated that all service books according to the Sarum Missal were to be defaced/destroyed: ‘utterly abolished, extinguished, and forbidden’.6 In 1549 during Edward’s short reign, the Book of Common Prayer was published in English. It was based largely on the Sarum Missal. More changes came about once again, however, in 1553. Queen Mary I’s restoration of the Roman church to these isles, brought back the Sarum Use throughout her reign from 1553 to 1558. There is evidence in Rochester’s printed Sarum of both its use in 1543 (Henry VIII) and again in the reign of Mary Tudor. On the final paper leaf of the book is a handwritten note in English which reads: ‘The yeare of our Lord God: M.D.xliii Thomas Welles was crystynned the [date in numerals] day of August.’ Whether a few Benedictine monks still remained in the Priory just after its final closure (1542) or a new organisation of clergy had replaced them by 1543, this well understood service book was clearly still in use.

Carefully glued in at a later date after page 270 is a paper leaf in a flourishing Tudor hand, which could provide evidence of the Missal being in use during Mary I’s reign. It reads at the top:

Prayers or collectes to be sayed in the masse for the quenes hyghnesse beying with chylde marias.

It would appear that this could be a reference to one of the supposed pregnancies of Queen Mary I, perhaps the second as the first was considered to be a phantom pregnancy, the second now considered to be a tumour.

On the accession of Queen Elizabeth I the ‘Sarum Use’ was finally banished by Royal Injunction in 1559, just as it had been in the reign of Edward VI.

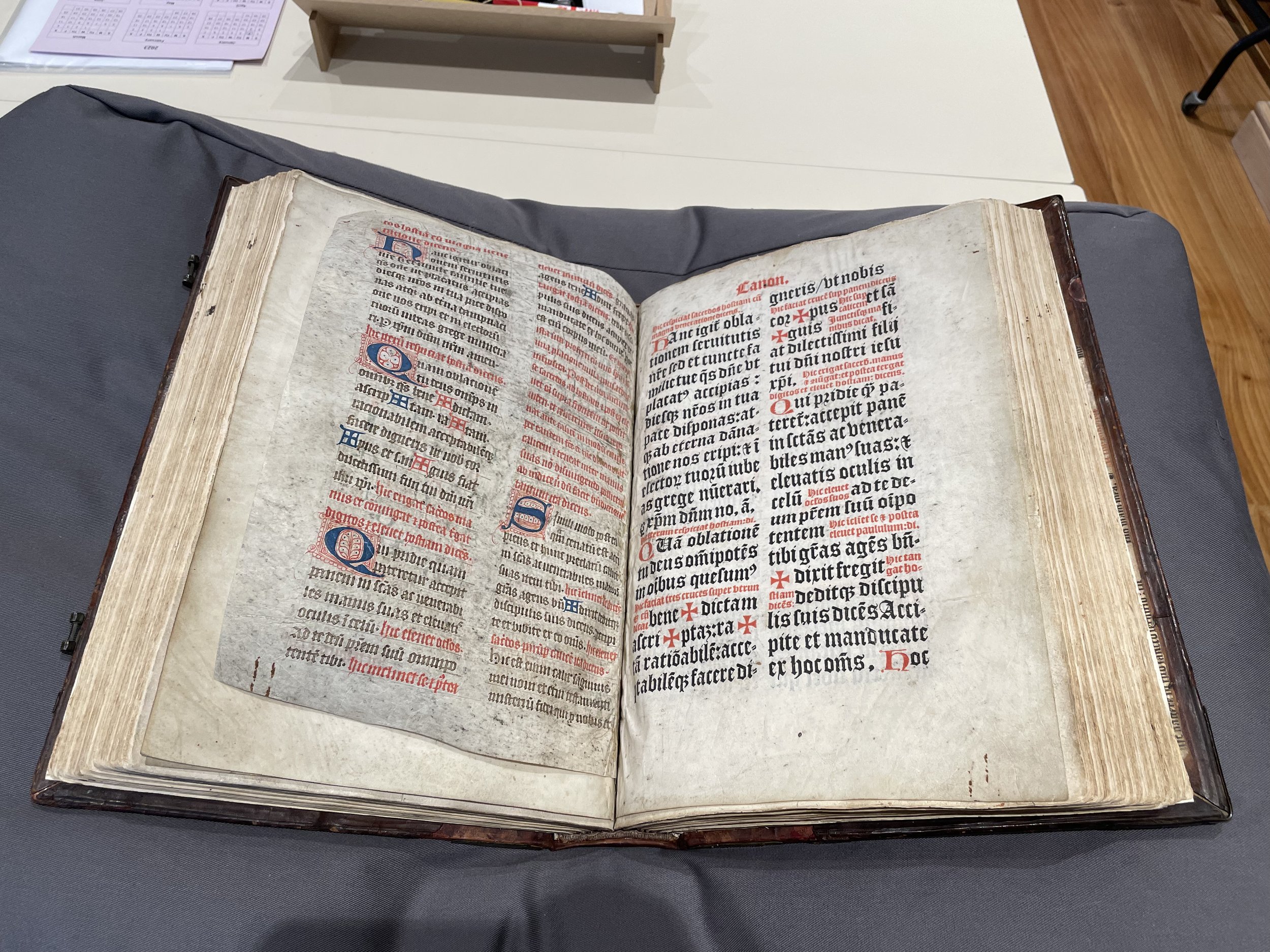

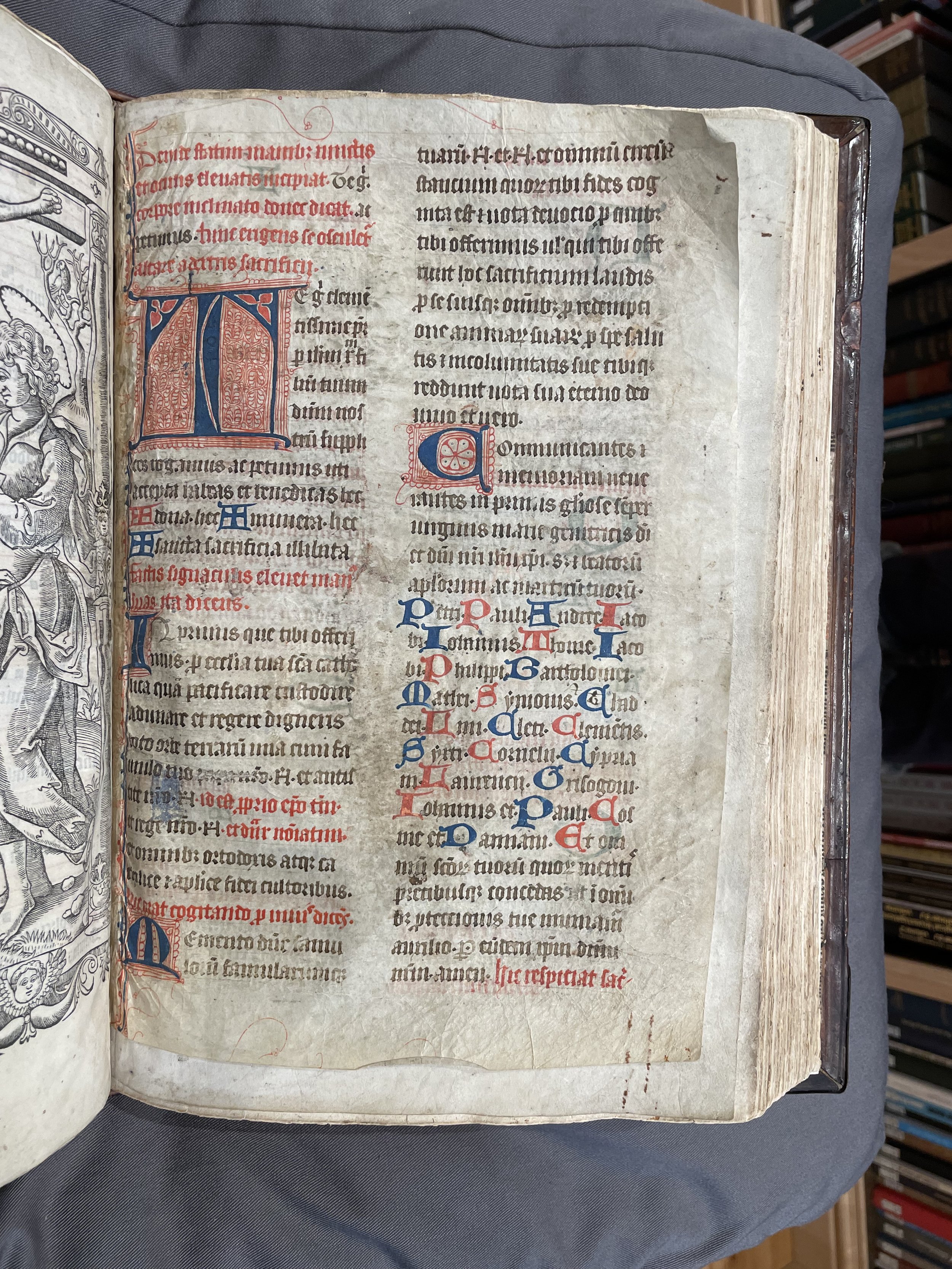

To return to the volume under discussion it is in Latin throughout, well printed and surprisingly straightforward to follow date-wise. It contains clear lettering defining individual services; in red (rubrics) used by those clergy or monks leading the services and in black for the congregants. A crisp block printing in black on white velum of Christ crucified, with an angel to his left-hand side, with his mother Mary seated at his right, and another woman standing at his right, is bound into the centre of the book.

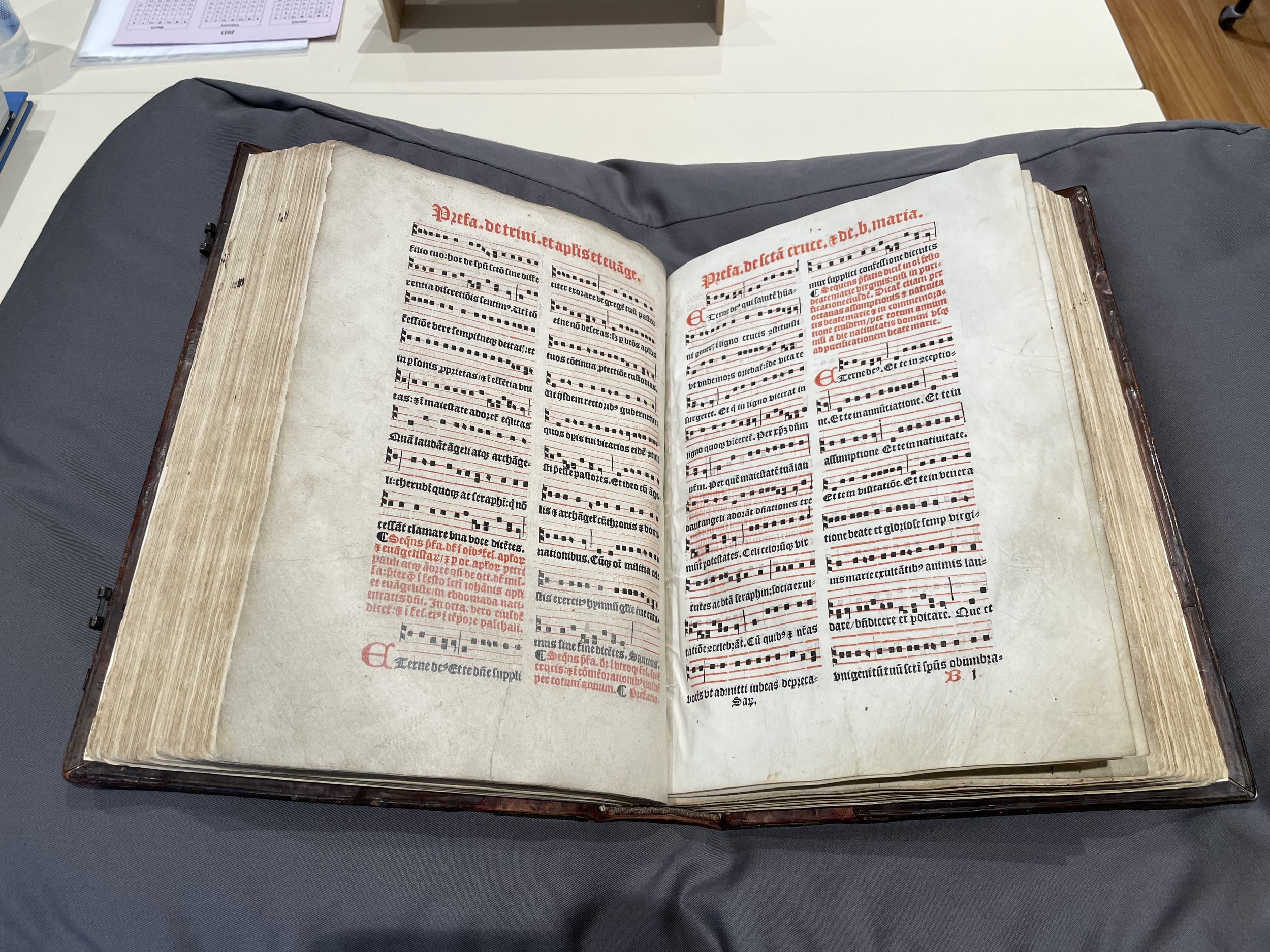

Following this is a velum leaf, smaller in dimensions compared to the rest of the pages, in a clear hand, in faded black ink with much decorated blue and red capital lettering, both on recto and verso. Is this a precious retrieval from a previously valued manuscript important for the monks to wish to save and retain! Many leaves of plainsong are also contained towards the centre of the book. It is interesting to think that the monks/clergy might still, on occasion, be using the ancient form of music at this date. Altogether the Missal is in very good condition. It is clear that it has been cared for and there is no evidence of destruction (or glossing). That is with the exception of the paste-downs inside front and back boards, despite the Injunctions for the same by Edward VI and Elizabeth I. There is so much more history contained within this book, and its predecessors, to allow us to learn how the Christian faith was disseminated, celebrated, understood and valued by the faithful – so much a part of their lives.

Beverley Dee Jacobs

September, 2023.

Footnotes

Use your browsers 'back' button to jump back to the text.

1 Sarum being the Latin abbreviation for Sarisburium meaning Salisbury.

2 Reverend Canon Professor J. Robert Wright; Historiographer of the Episcopal Church: The Sarum Use.

3 B.M.Royal 12 F.viii: ejoh. Saresberiensis. s.xii/xiii. Small Italic s. preceding xii/xiii indicates provenance. In the case of Rochester the clear patristic hand favoured by their Scriptorium. N.R.Ker; Ed: Medieval Libraries of Great Britain; London 1964: Pp:ix/x.

4 Mary P. Richards: Texts and Their Traditions in the Medieval Library of Rochester Cathedral Priory p.1, Philadelphia, 1988.

5 Reverend Canon Professor J. Robert Wright; Historiographer of the Episcopal Church: The Sarum Use.

6 As above, p.3.