Bishop Gundulf's cloister, c.1080-1114

/Cathedral Archaeologist Graham Keevill discusses recent archaeological investigations beneath the Cloister Garth revealing what is thought to be the foundations for Bishop Gundulf’s short-lived cloister.

Limited trenching undertaken within the lawned area in 2015 revealed the remains of very impressive gravel foundations. That these foundations supported a stone structure was shown by the small areas of masonry that survive surviving on the northern foundation of this building. After the demolition of this structure the garth was, apparently, kept as a mown lawned area (as now) for the whole of the medieval period (Hope 1900, 29). This long standing lawn goes someway to explaining how the foundations of the late eleventh century east range survived so well (Keevill and Ward 2019).

Most people will be familiar with radar (Radio Detection and Ranging, or Radio Direction and Ranging) in the context of the detection and tracking of objects such as aeroplanes and ships. The method uses radio waves to determine and measure the range, angle and speed of a target, often across extraordinary distances. Fewer people will realise that radar is also a very useful survey tool for archaeologists because the radio waves can be directed downwards into the ground rather than up into the air – hence the term ground-penetrating radar, or GPR for short (talk to an archaeologist for any length of time and you will soon realise that we love acronyms …). When the waves hit a buried target such as a wall, this can be detected as a distinct change in the reflected radar signal. If more of these reflections are found, the radar will start to build up a picture of the buried building (rather than the flight path of an aeroplane).

Radar has several great advantages for archaeologists. First, it is non-destructive, causing no damage to the ground. More importantly, hard surfaces like paving or concrete are usually no impediment – GPR sees right through them, unlike standard geophysical survey methods such as earth resistance and magnetometry, which do not work in such conditions. The method also works to much greater depths – usually around 2.5m-3m, whereas other methods struggle to penetrate beyond 1m. At the moment GPR is also unique in providing three-dimensional imaging, in other words a series of plans of what has been detected at different depths below surface. These are referred to as ‘time slices’. This is priceless for archaeologists because it equates well with the idea of stratigraphy – broadly speaking, that something buried deeply is usually older than something at shallow depth. GPR can therefore be an extremely useful tool for archaeologists. There can be drawbacks, of course: the sheer quantity of data being collected means that collating and interpreting it is time-consuming and thus expensive (as well as requiring considerable skill). There is also no guarantee that GPR will work – the results can be quite disappointing, especially so if you have committed a few thousand pounds to doing the work! Nevertheless, a series of GPR surveys over the past 10 years with improved technology and resolution has steadily built up a picture of what lies beneath our Cathedral.

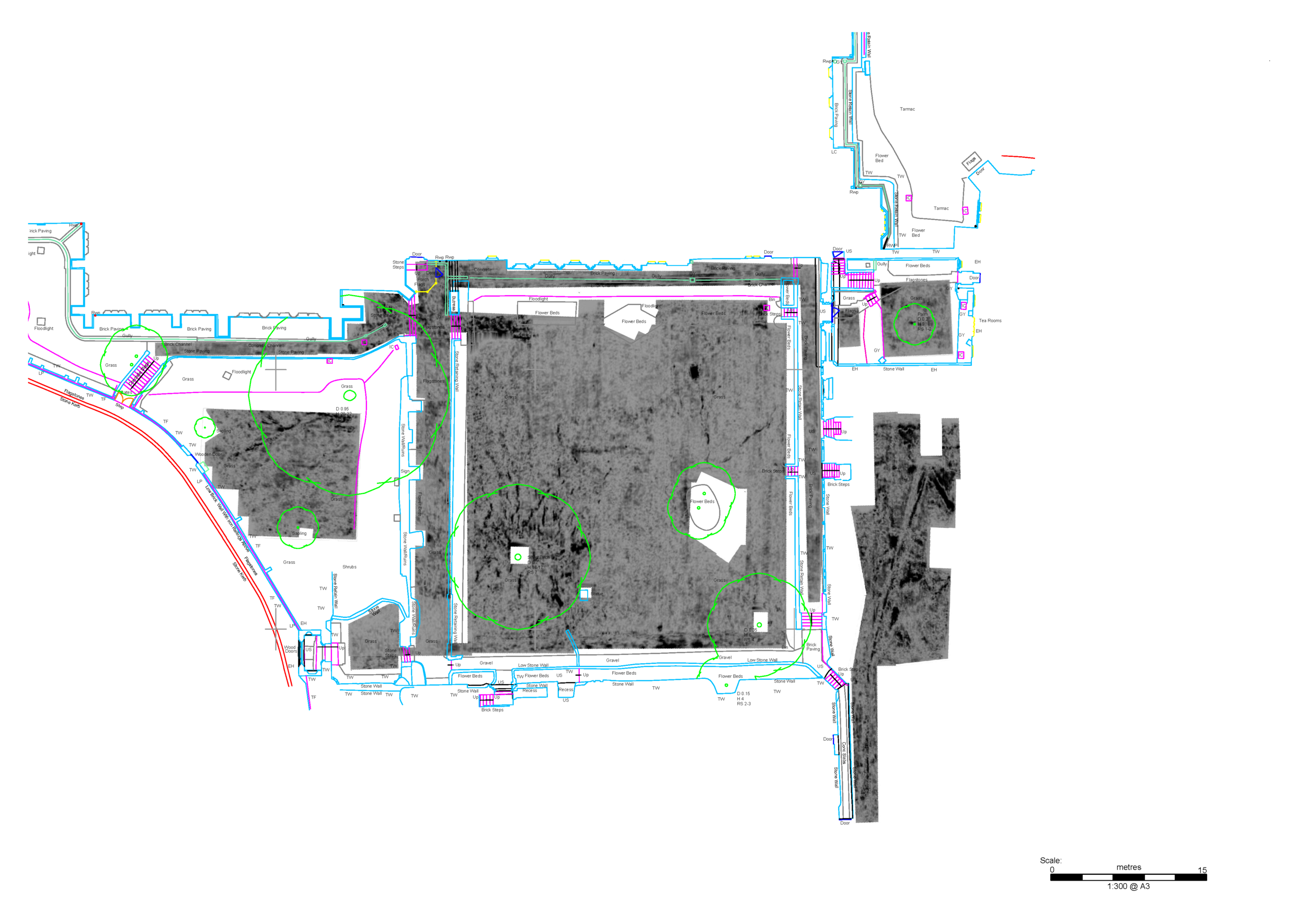

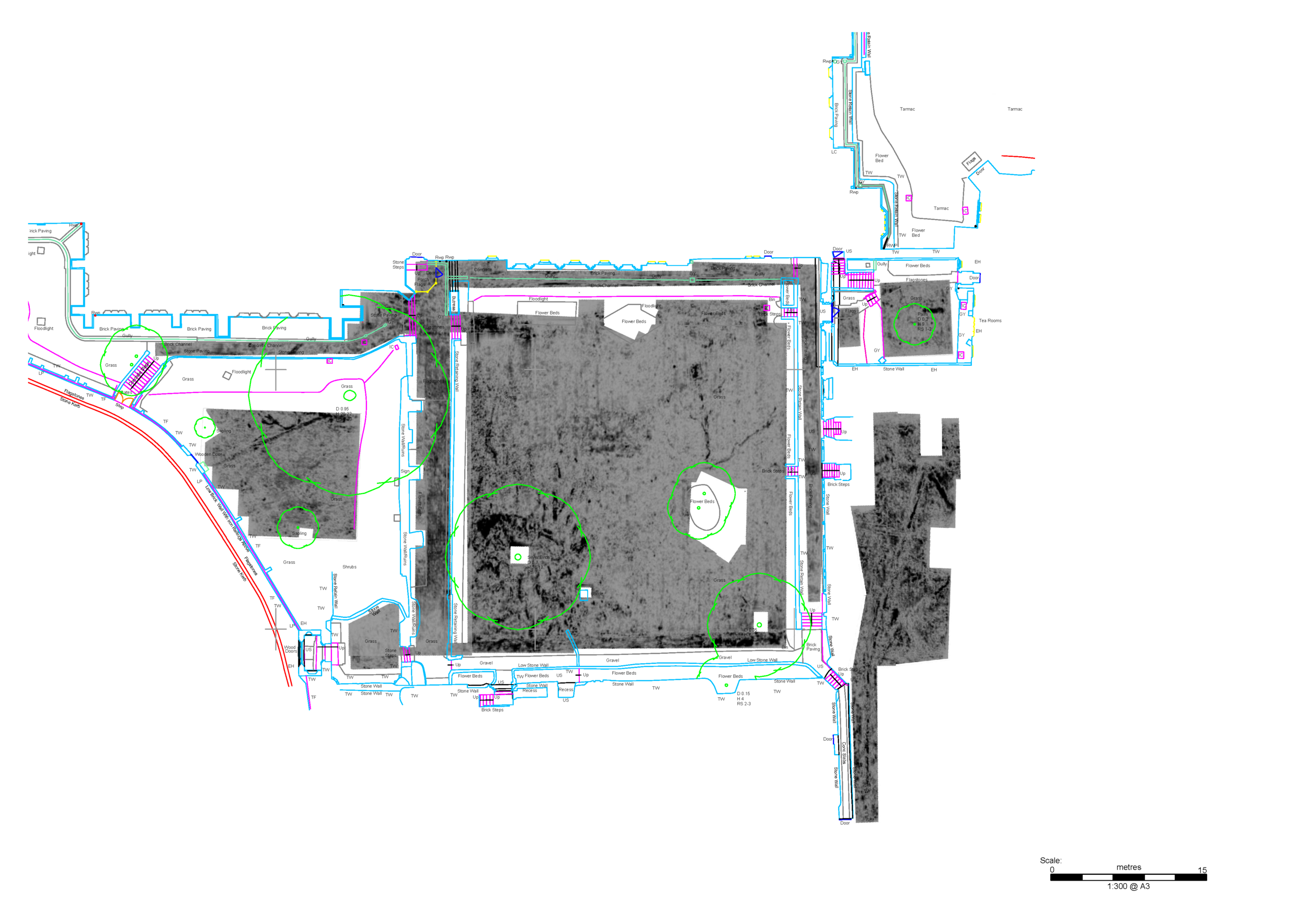

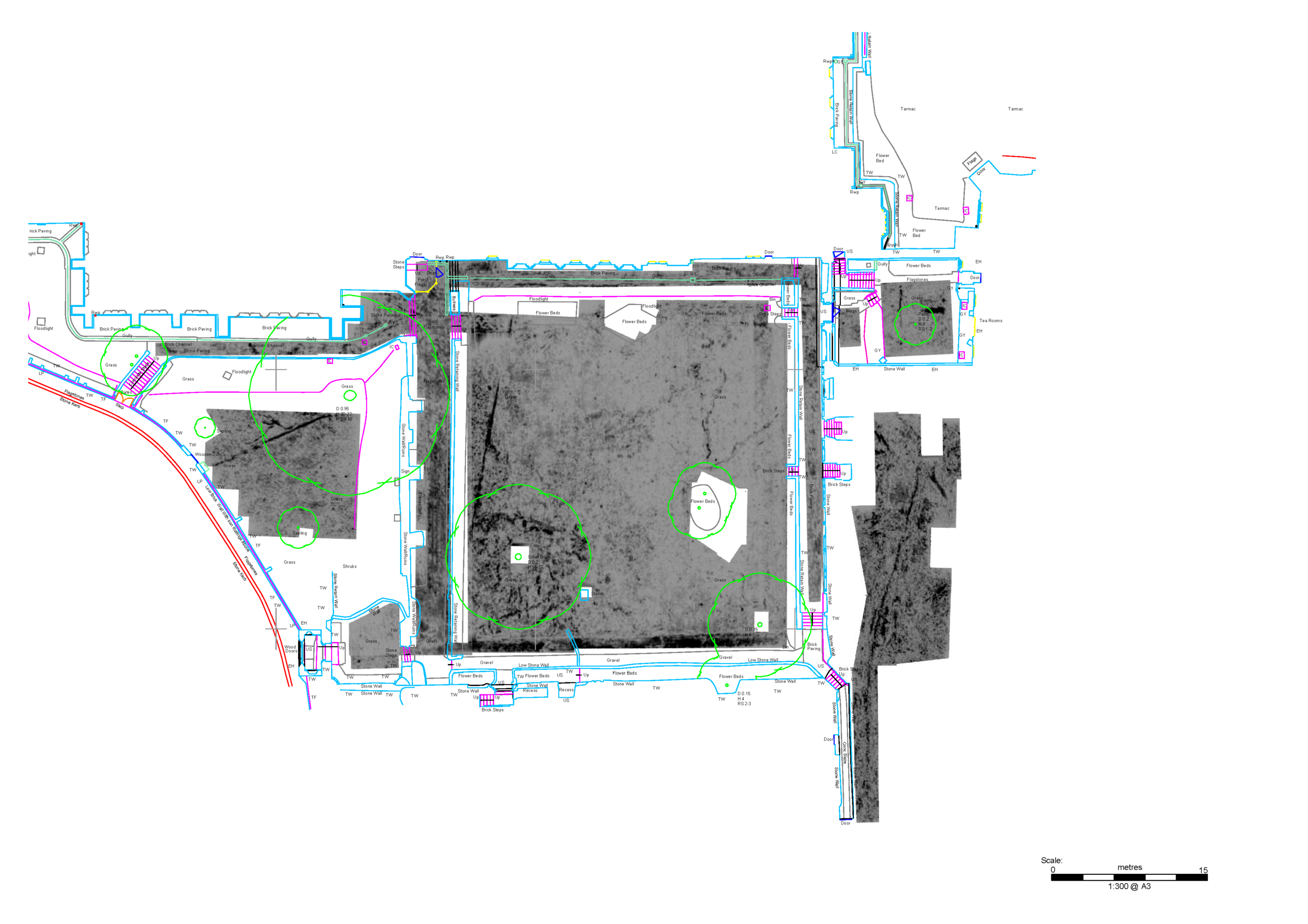

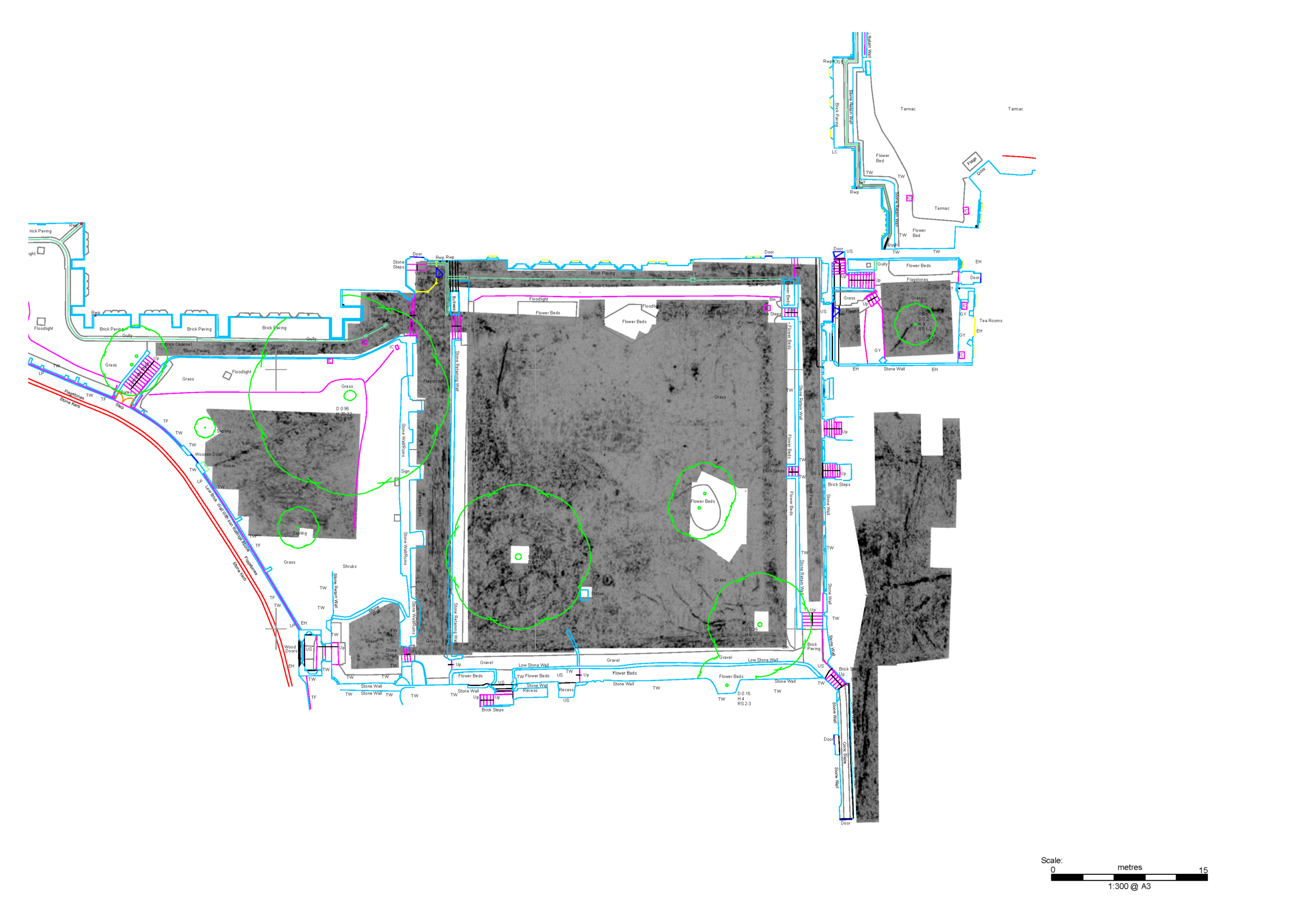

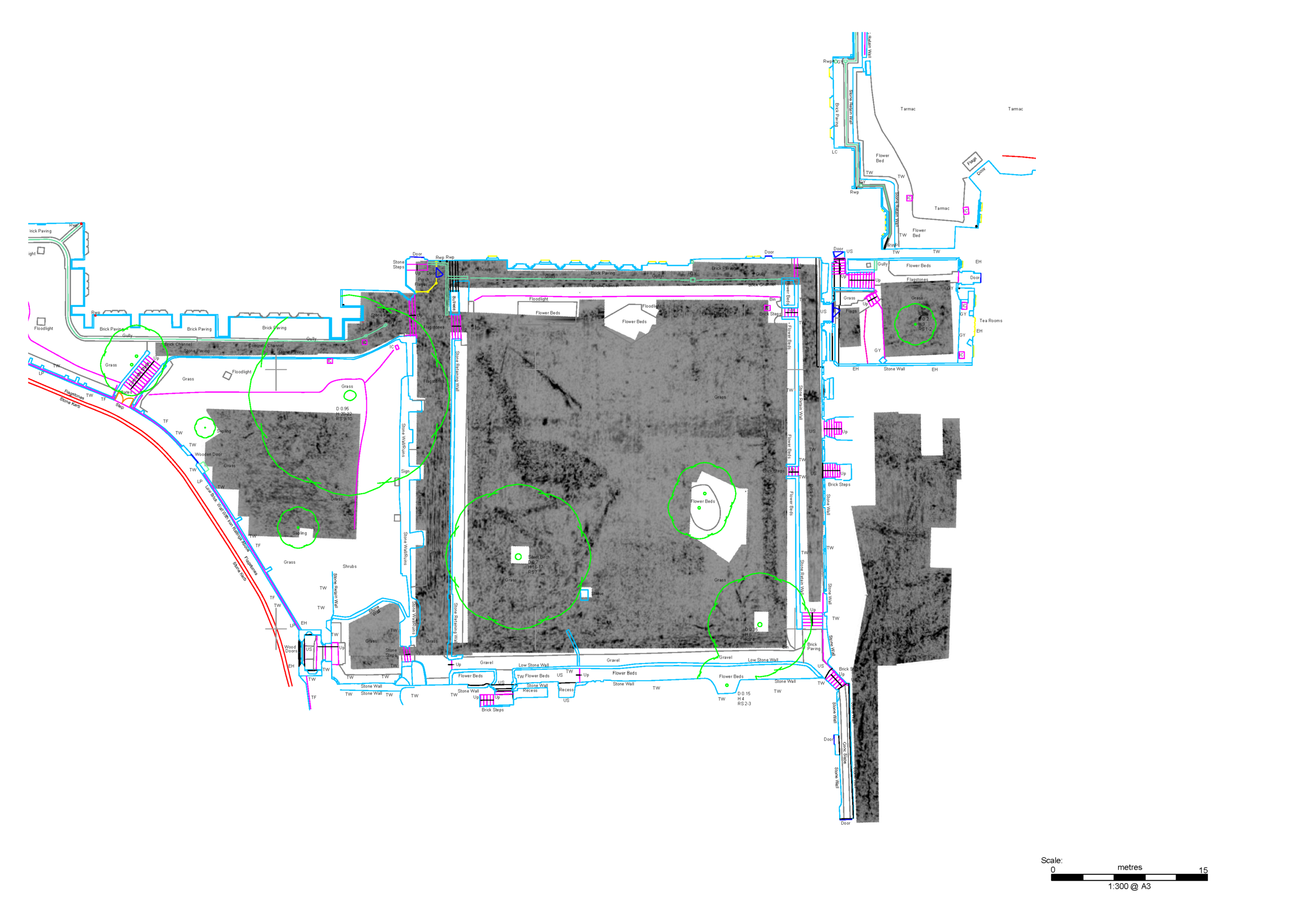

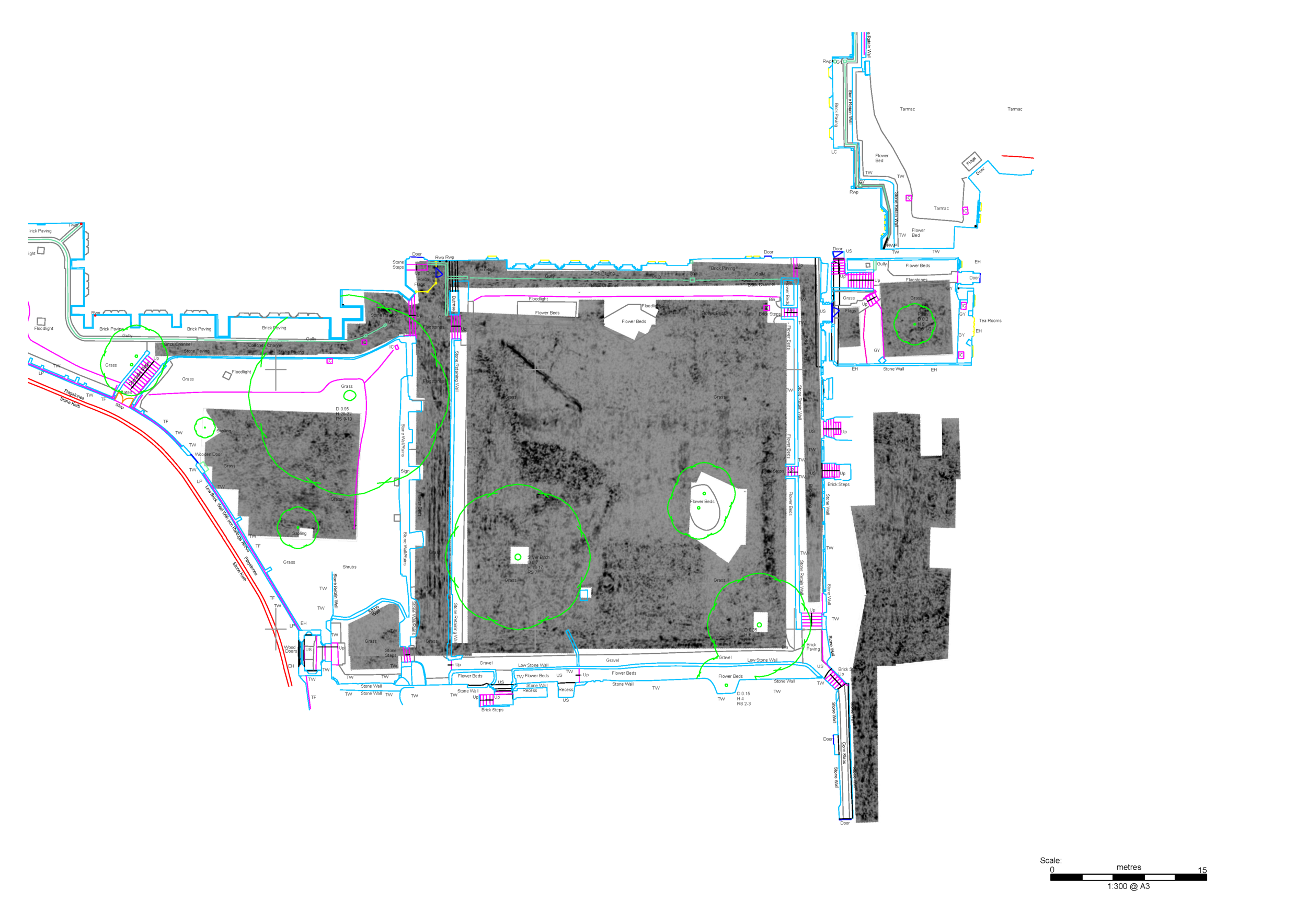

Overview of GPR surveys 2010 to 2018.

I was successful in winning a free GPR survey in SUMO’s Great Summer Competition during 2017, having put forward a very strong research proposal to examine the cloister area at Rochester Cathedral. Our discovery of early Norman foundations here in 2015 during the Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions work had been tantalising. How far did those foundations extend, and what might they represent? Winning the SUMO competition gave me the perfect chance to test this with GPR. Most of the cloister is protected in law as a Scheduled Monument, so permission was needed to carry out the survey. Historic England were as keen as us to learn more about the 2015 discoveries, so they readily granted us the necessary licence. Thus on 25 and 26 September 2017, SUMO Stratascan surveyed four areas: the cloister garth and its surrounding walkways, the raised area on the west side of the cloister, the Chapter House, and the courtyard/car park on the south-west side of the Old Deanery (the site of the medieval monks’ dormitory, or Dorter). Despite challenges such as survey areas at different heights and some small/narrow areas (especially the east and north cloister walks), it very soon became clear that the results were good.

Richard Fleming of SUMO Stratascan surveying the north cloister walk in 2018, with the Chapter House in the background. Mounting the survey antenna on a small cart meant that the ground could be covered quickly despite the often fiddly nature of the survey areas.

GPR’s capability for seeing to considerable depths was crucial, because the remains found in the north cloister walk and the north-east corner of the cloister in 2015 were about 0.8m-1m below the lawn in the garth. We had only been able to record the tops of the foundations, because they had been exposed at the limit of the depth needed for the HTFE works. Preliminary results from the first day’s work showed that the walls of the old Prebendal House in the south-west corner of the garth were easily identifiable in the upper 0.6m of the survey data, while drains or pipes were evident in all the areas. Even tree roots showed up clearly in the garth. Even at 0.45m some clear linear features could be seen along the north and east sides of the garth. Were these only Victorian footpaths, or were they a hint of what lay beneath? Some modern services, tree roots and the walls of the early 19th-century Prebendal House all show up clearly, proving that the GPR was effective.

Time slices for each area of the cloisters survey. Click/touch to change depth. Animated versions provide the remarkable experience of seeing the entire 2.5m-3m depth of archaeology gradually being ‘stripped’ away (available here).

In the garth, the northern and eastern features ‘fade’ slightly as the depth approaches 1m – but by this stage it was hard to see them as simply paths: after all, they were already more than 0.5m thick. Things became steadily more interesting immediately below 1m – the same depth at which we saw the early Norman remains in 2015. For a start, features running parallel and at right-angles to both of the higher ones become clearly apparent, as shown on Figures 3 and 4. These were extensive and substantial, with a north-south building on the east side of the garth being especially impressive. Remarkably, this had an extension eastward at its north end, seemingly with a polygonal apse (now under the east cloister walk). Further buildings or features are present on the north and west sides of the garth as well. The features along the east side continue to depths of around 2.3m, but most of the others seem to stop short of this – around 1.5m below ground.

We will come back to the interpretation of these remains in a moment – but what of the other areas? I hadn’t held much hope for good results on the raised area on the west side of the garth, partly because two small test pits I dug here in 2011 suggested that thick layers of demolition rubble would be present. I needn’t have worried: the GPR saw through this material and revealed the presence of two substantial buildings on the west side of the Cellarer’s (west cloister) Range at a depth of c 1m below ground and extending down towards the limit of survey at c 2.3m. The southern one was rectangular and may have been a medieval porch leading into the range. The other ran west towards The Precincts at the north end of the raised area, and coincides with a leasehold house shown on Danial Alexander’s 1801 plan of the cathedral and its properties. It was evidently not one of the prebendal houses. Perhaps it too had medieval origins.

Results in the Chapter House and the site of the medieval dormitory to its south were not quite as impressive, partly because of extensive modern service runs (drains etc). Even in these spaces, though, substantial traces of original foundations and possible floor levels could be seen. In both cases the foundations probably relate to columns which would have run centrally along the buildings to support vaulted ceilings or roofs over them.

One question needs to be addressed before considering the nature of the remains found by the GPR. Why aren’t they Roman? The old city wall of that date forms the rear (south) side of the cloister, after all, and must still have been a standing feature in Saxon and Norman times. There are several answers to this. The most important one comes from the 2015 excavations. The foundations revealed there had been cut into a ‘dark earth’ layer, which in turn overlay a Roman topsoil. We saw the same sequence in a test pit dug at the north-east corner of the cloister walks in 2012. These dark earth layers are quite common features in Roman towns, forming once they had passed into disuse (or at best minor habitation) after the end of Roman rule. Dating evidence from them is rare, but everything about the Rochester example points to a post-Roman/Anglos-Saxon date. Just as important, the shelly mortar used for some of the foundations is typical of Norman work in Rochester. At a more circumstantial level, the location just inside the walled town seems odd for what would have been an extremely large building for Roman Rochester – though to be fair we are hampered here by the surprisingly limited evidence for the city in this period. There would also have been an earth rampart inside the wall from the late second century AD, which would have restricted any building work here from then until the medieval era.

Unfortunately, but as expected, no clear evidence for the Anglo-Saxon cathedral complex was found. The distinctive alignment of the building remains found under and east of the West Front, if continued elsewhere, would be very distinctive. Alas, no such remains were found.

Interpretation of the GPR data showing the layout of the earlier Norman cloister as revealed by the survey, later medieval remains, and the early 19th-century Prebendal House. This has been simplified for clarity, and does not include all of the archaeological detail found in the 2015 excavation.

So we return to the features found in the cloister garth. The foundations we had found in the north cloister walk and garth by excavation had to be earlier than the surviving remains of the east cloister range and Chapter House. Opinion is still divided about the exact date of these, but for current purposes we can suggest a date of around 1120-1150. We had discovered something earlier, and I suggested in 2016 that the remains we had found then might belong to Bishop Gundulf’s work. There were some problems in how to interpret what we had found, but many of those have gone away with the GPR results. In particular, we can now see that the ‘narrow’ building we thought might have been his Chapter House was much wider than the excavations suggested (albeit on evidence from very narrow drain trenches). It also sits across the north end of a long building range stretching south along most of the garth. The GPR data isn’t clear about how the south end of this range was finished off: there is no obvious trace of a south wall. Evidence for a southern cloister range in front of the Roman city wall is also limited, although a broad rectangular feature to the west of the east range at a depth of 1.2m (see Figure 3) might belong to such a range (perhaps of timber?). This would probably leave room for the Roman wall’s internal rampart to have survived as well. These are questions which will have to wait for an answer. We can say with reasonable confidence, however, that an earlier Norman cloister has been found, inside and thus a little smaller than the current one. The west and south cloister ranges may well have been common to both versions: if so, the early-mid 12th-century version only needed to be enlarged to the east.

Reconstruction by Jacob Scott of Bishop Gundulf’s Cathedral and cloister circa 1100 AD (outline of Anglo-Saxon cathedral in pink and the present Cathedral in green and blue), based on interpretation of recent archaeological excavations and the 2018 radar survey.

As for the features found on the north side of the garth, these may well have been associated with gardens and other facilities within this first Norman cloister. All in all these are remarkable results, and they certainly demonstrate why some sites like the cloister need to be protected as Scheduled Monuments.

Graham Keevill

Rochester Cathedral Archaeologist

Acknowledgements

Figures are adapted from those provided in the original archive reports. We are extremely grateful to David Elks, Richard Fleming and Magdalena Udyrysz of SUMO Stratascan for their excellent work on this project. More information about Stratascan’s work can be found here. We are also grateful to Alan Ward for commenting on an earlier draft of this article.

This post is part of a series on the Medieval Priory of Saint Andrew at Rochester Cathedral.

Priory and Precinct

The Benedictine Priory of Saint Andrew at Rochester Cathedral was founded in 1080 by Bishop Gundulf and dissolved in 1540 by order of King Henry VIII. The ruins of the priory survive on the south side of the Cathedral, centred on the Cloister Garth.

EXPLORE

Explore the studies, conservation and excavations revealing the sites 1,400 year history.