Hidden Treasures at Rochester Cathedral: archaeological investigations 2011-2017

/Introduction by Graham Keevill to the report on the archaeological surveys, excavations and watching briefs at Rochester Cathedral during the Hidden Treasures Fresh Expressions Project 2011-2017.

Graham Keevill (GK) has been the Dean and Chapter of Rochester’s Cathedral Archaeologist since 2006. He is also the Cathedral Archaeologist for Blackburn, Salisbury, and Christ Church Oxford. He directed all stages of the archaeological work during the Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions project, and carried out much of the work himself. He also commissioned many specialist surveys and reports (through and on behalf of the Dean and Chapter). These are referred to at relevant points in this work.

Alan Ward (AW) has carried out an enormous amount of archaeological work in and around Rochester, including at the Cathedral, since the late 1980s and early 1990s. He knows the archaeology of the town better than anyone, and its history better than most. He carried out much of the excavation and recording work during the main contract phase of the Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions project in 2014-16 under the direction and on behalf of GK, and prepared a full draft report of this work in 2016- 17.

Cathy Keevill is a specialist in archaeological ceramics and other finds. She also participated in the Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions fieldwork.

Note on the orientation of Rochester Cathedral and its Precincts

For complex historical and topographical reasons, Rochester Cathedral is oriented from north-west to south-east. This is largely followed by the buildings and grounds within its historic and current estate, known collectively as The Precincts. The orientation largely reflects the pre-existing topography of the Roman town, but can make site descriptions overly cumbersome. It is a broadly accepted convention, however, to describe church buildings with reference to a ‘standard’ east-west orientation even when the reality is significantly different from this, as at Rochester. This convention - the ecclesiastical compass - is followed throughout this report.

Aerial photograph of Rochester Cathedral. The cloister is to the right of centre, with the Chapter House and Old Deanery (now the St Andrew’s Centre, partly used by the King’s School) to its right. The current Deanery, College Green and Southgate – formerly the Bishop’s Palace – are at bottom left. Photograph by kind permission of Adam Stanford.

Steps and access at Rochester Cathedral

England’s cathedrals are among its greatest treasures, displaying a remarkable variety of size, history and architectural character. Their primary purpose and use is of course worship and mission for the Christian community on many levels, from local to national and beyond. It is well recognised (and has been for many years), however, that cathedrals also have a wider role as visitor attractions for people of many faiths – or none. Most of them are important for the local economy, and contribute to community life in myriad ways. Yet they are often challenging places, especially among the older buildings, where access is concerned. They are by no means unique in this: historic buildings often present difficulties of multiple floor levels with awkward means of access and egress between them. In some cases these challenges were deliberate, and were designed to control or manage security and circulation around a building or site: but in a modern world where inclusivity of access is a rightful aim and discrimination is unacceptable, how people are able to enter and use an old building can present real, major issues and conflicts. That was certainly so at Rochester Cathedral in the third millennium AD. How those challenges were addressed, and what discoveries were made as a result, is the subject of this report.

Plate 2: The cloister and eastern arm of Rochester Cathedral looking north-west. The two-storey building at bottom right is the Chapter Library (on the first floor), with the vestry beneath.

Rochester Cathedral has three main floor levels internally: the first covers the nave, its aisles, and the greater transepts. Level access is available directly from the outside via the North Transept: the external ground level of c 9.05m aOD (above Ordnance datum) here is the same as the Cathedral floor. Hidden Treasures at Rochester Cathedral: Archaeological Investigations 2011-2017 13 The topography, however, means that the ground outside the West Door is at c 9.67m aOD, 0.67m higher than the floor in the nave and its flanking aisles, meaning that a flight of four steps is needed here. The interior has a second ‘ground floor’ level in the eastern arm, although the floors here are not all at the same height: the Quire floor is 1.5m above the nave, requiring a raised dais and ten steps in the crossing to get up to it. The north Quire Aisle starts at the same level as the North Transept but eight steps – the Pilgrim Stairs – are needed to get to the raised eastern part, which is 1.2m higher. The floor then slopes gradually up, but is still 0.5m lower than the lesser north-east transept – so another three steps are needed at the threshold between them. This is also 0.45m higher than the Quire floor, so steps are needed at its east end as well. The South Quire Aisle needs 12 steps (The Kent Steps) to rise almost 2m up to the lesser south-eastern transept. Finally the presbytery, St John the Baptist Chapel to its north, and Chapter Library to its south, are all at a slightly higher level than the lesser transepts – so a few steps are needed at these junctions as well.

The South Quire Aisle and the Kent Steps looking east in 2014, before the main contract began, showing the change in floor levels. The timber structure to the left hid the wheelchair lift.

Such a complex pattern of floor levels (and steps) is need because the eastern arm is raised over a major historical feature of the Cathedral: its crypt. This has three major historical components. The first and earliest underlies part of the Quire and its aisles, and is of early Norman date (it is often referred to as the Gundulf Crypt after the first Norman bishop of Rochester). The rest of the eastern crypt is about a century later, and was rebuilt after fire severely damaged much of the Norman east end in 1179. The vestry under the Chapter Library, however, is later still (our third phase), belonging to the 14th century. It is accessed from the main crypt underneath the lesser south-eastern transept, and its floor is 1.2m higher – so six steps are needed here. We should also mention here that the Norman part of the crypt has a lower floor than the rest, requiring … more steps.

Levels are also challenging externally at Rochester Cathedral. We have already seen something of the complex external topography: generally the ground slopes down from west to east and from south to north (as it always seems to have done). This overall pattern does not account for some more dramatic level changes, especially along the south side of the cathedral. These centre on the site of the monastic cloister. Most unusually, this is located alongside the eastern arm of the church rather than the more conventional position towards the west (here, the nave south aisle and Lady Chapel). The cloister comprises a roughly square central garden (the Garth) with the Cathedral on its north side, the ruined Chapter House and remnants of the Dorter (dormitory) range on the east, the old Roman city wall on the south (the Fratry would have lain on its other side), and the Cellarer’s Range on the west. The history and archaeology of the cloister forms an important part of this report, but for now suffice to say that ground levels in and around it had developed a complexity all of their own: to start with, the whole area was lower than the nave floor – so steps were needed to get down to the cloister level. The north cloister walk then sloped down to the east, but was still higher than the east cloister walk. The west and south walks were roughly level with the Garth, but because of this all of them were substantially (0.7m-0.9m) higher than the east and north walks. Several more flights of steps were needed to counteract these complex changes of level.

Access to the Cathedral: meeting the challenge

The Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral are responsible for the management and maintenance of the building and grounds. This includes ensuring compliance with the wide-ranging provisions of the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, as far as can be achieved while avoiding unacceptable conflict with or detriment to the historic fabric of the place. Chapter has always been very conscious of its responsibility to the widest possible community of interests in running the Cathedral, not just in recent times but going back decades and even centuries. One recurring theme, however, has been the limits of its available funds: Rochester has always been the ‘poor relation’ of Canterbury, and is still one of the poorest among England’s 42 Anglican cathedrals. The will to tackle access issues in the light of the 1995 Act was not in doubt: but the resources certainly were.

Despite having very restricted funds available to do so, Chapter had begun to address inclusive access soon after the 1995 Act. A chair lift had been constructed on the Kent Steps in 1998, for example, to provide wheelchair and other access between the western and eastern floor levels within the Cathedral. A timber screen was designed by the then Cathedral Architect, Martin Caroe, to reduce the visual impact of the lift on this very fine part of the building. These improvements were funded by the Friends of the Cathedral, then and now one of its most important supporters (and funders). Attempts had been made to improve the accessibility of the cloister as well, although the narrow north walk, the level changes and steps seemed intractable.

The establishment of the Heritage Lottery Fund as a major source of grant aid for historic sites and buildings transformed what could be achieved throughout the conservation and heritage sector. The Dean and Chapter of Rochester recognised this, and commenced a major review of access in and around the Cathedral at the beginning of the new millennium. The first fruit of this was the Hidden Treasures, Untold Stories project in 2008-10, with funding from the HLF and others. As the name suggests, this sought to reveal the many-faceted and fascinating stories that can be gleaned from and of the Cathedral’s historic fabric, while also making great improvements to its accessibility. A new fully accessible toilet was provided in a chamber off the South Quire Aisle, for instance, while glazed porches were added inside both the West Door and the North Transept entrance (the latter being formally adopted as the primary entrance for inclusive access). New interpretation facilities were provided, and various other improvements were made within the Cathedral and in the cloister. Archaeological monitoring and recording was an essential part of the project (Keevill 2010; Keevill and Underwood 2010b).

The Hidden Treasures, Untold Stories project was a considerable success, but much remained to be done to improve inclusive access. That project could not address the issue of the varied floor levels inside the building, or indeed in the cloister. The crypt in particular remained completely inaccessible to wheelchair users and many others. It was also an under-used space, with poor floor finished and lighting, and a far from ideal environment. The HLF supported the idea of a second project, Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions, to address these and many other issues. Chapter had also secured several other important sources of funding. Thus a much larger project (planning for which had started actively in 2006-7) commenced, with the initial feasibility and design stages largely taking place in 2009-12. The centrepiece was to be a new vertical lift in the south-east corner of the South Quire Aisle, which would provide fully inclusive access between all three of main floors in the Cathedral: crypt, western arm and eastern arm. Other areas covered included: a complete overhaul of the crypt, with new floors, heating, environmental control, exhibition spaces and a new Servery/catering facility; full conservation and refurbishment of the Chapter Library and the vestry beneath it; reconfiguration and landscaping of the cloister and its walks to create step-free access to all sides, though steps at the south-east corner still could not be avoided; replacement of the existing porch at the entrance to the South Quire Aisle (it could no longer function with the new external floor levels); a new external staircase for the Chapter Library inside the Chapter House, replacing one built probably in the early 19th century which made the Chapter House very difficult to use; and various other changes. It was clear that this would be a wide-ranging, complex and difficult project. So it proved to be, for reasons which are described later in this report.

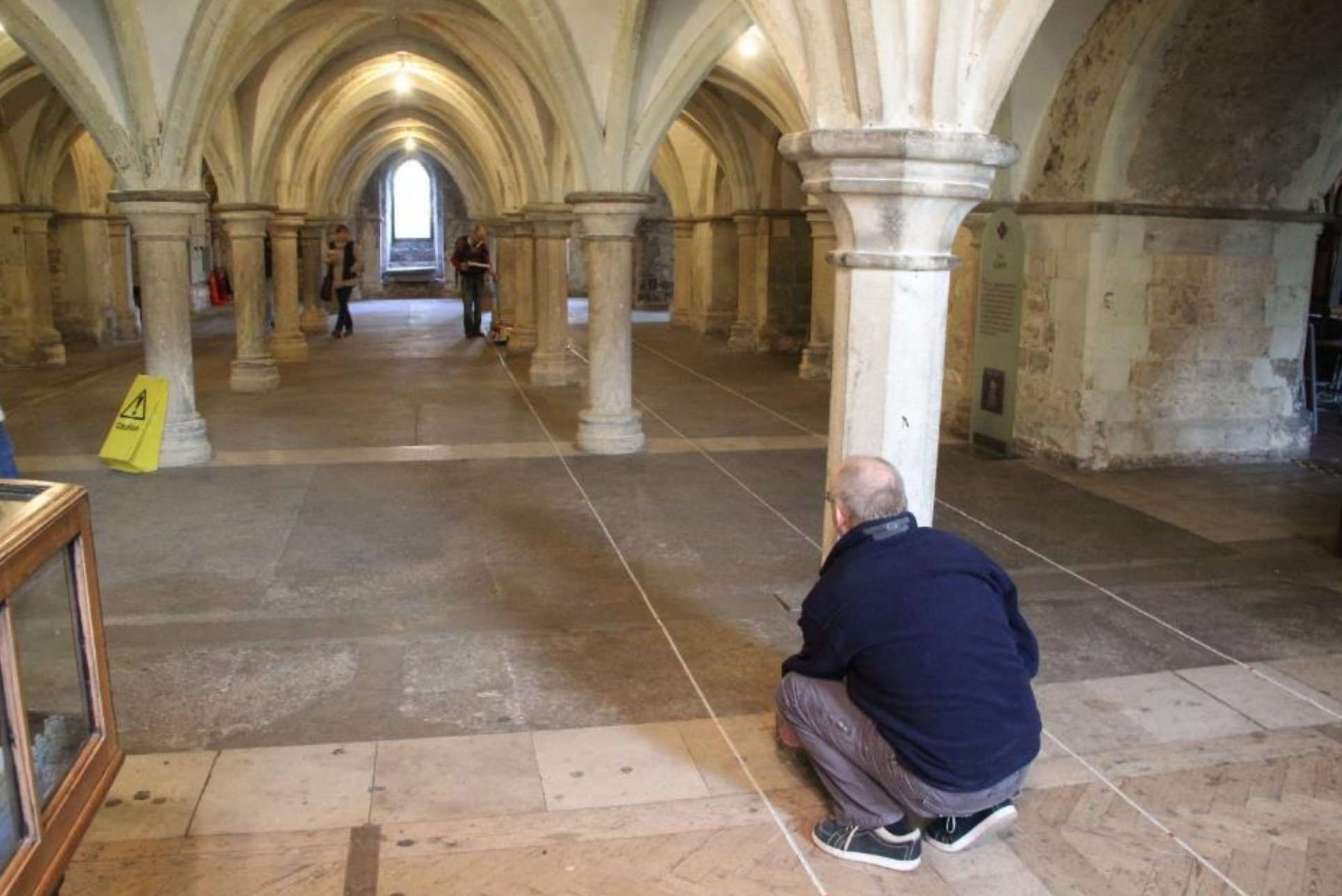

The GSB team carrying out a GPR survey in the main crypt in 2011, looking north. Note the varied floor finishes and poor lighting.

The main contract achieved practical completion in 2016, but due to issues as diverse as asbestos and archaeology the work was well behind programme – and over budget. This meant that some aspects of the scheme had to be postponed until further funds could be raised. Thus two elements were carried out during 2017-18. The first saw the underground heating system in the crypt completed by the introduction of air ducts within an existing shaft on the north side of Gundulf’s Crypt. The second established new wash-up and food preparation facilities in a small area on the east side of the main crypt. This had been an external space – colloquially known to all as the Pigeon Parlour, for obvious reasons – but had been roofed in during the main HTFE contract. A watching brief covered both these pieces of work, but only the shaft is considered here because nothing of note was found in the Pigeon Parlour.

Archaeology and HTFE

Rochester Cathedral is a Grade I listed building, designated under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1991. Like most of England’s Anglican cathedrals, however, the building has ecclesiastical exemption from the usual terms of the 1991 Act (and the planning system generally) under the Care of Cathedrals Measure 2011 (this replaced the original 1990 Measure). The Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England (CFCE) nationally, and the Fabric Advisory Committee (FAC) locally, are in effect the cathedrals’ local planning authority, determining applications for projects which would normally require planning permission and/or Listed Building Consent. This only covers a specific area defined as the ‘Red Line’ (at Rochester comprising the whole of the cathedral building), but not the grounds around it, which fall under the usual civil procedures. CFCE therefore dealt with the full application to carry out the HTFE project in several stages, devolving matters of detail to the FAC as appropriate. The first stage took place in the early days of the design process, with the general concept design approved on 10 December 2010; at this stage permission to proceed with the crypt element was reserved for further discussion. Full permission was granted on 23 January 2013, subject to 15 conditions. It is a measure of the Cathedral’s (and the project’s) archaeological sensitivity that six of these conditions (3-8) directly addressed archaeological issues: some required detailed mitigation of impacts through excavations and watching briefs (Conditions 3 and 4). Condition 5 covered the potential for finding, and how to deal with, human skeletal remains. Condition 7 provided a ‘backstop’ in case unexpected and significant discoveries were made, in which case work was to cease and CFCE were to be consulted on how to proceed. To a degree this was a standard condition, but it did recognise that it was difficult to gauge archaeological sensitivity in large, complex projects of this sort even after a long process of investigations (see below). Condition 7 proved to be prophetic, however, as described in detail in Chapter 4 (section 4.3.2).

The cloister to the south of Cathedral’s eastern arm is a Scheduled Monument (under the terms of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979), described as the remains of Rochester Priory cloister (National Heritage List number 1003405). The main contract involved several interventions below ground in this area. The enabling works had also involved ground interventions to the north of the Cathedral, partly within a second Scheduled Monument (one of several open areas within the Roman, Saxon and medieval town to be so designated: National Heritage List number 1003602). Thus application was made to Historic England (on behalf of the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport) for Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC) for these works. In fact two SMCs were required. The first (reference S00055343, 11 March 2013) covered the enabling works and the pre-contract designs for the cloister and the area in front of the Chapter House (its west wall is included in the Schedule, though its interior is not). The second (S00075656, 29 January 2014) superseded the first with respect to the full design of the cloister works. A variation of this was approved in writing on 28 July 2015 to cover the need to excavate a large soakway pit in the cloister garth. Civil planning permission was also needed for some aspects of the project, but archaeological issues were so comprehensively covered by the CFCE approvals and the SMCs that no additional requirements were included in this.

Work leading up to the main contract

Archaeological work leading towards the HTFE project had actually started as early as 2006-7, as part of a feasibility study on wheelchair access to the crypt and around the cloister. This included the hand excavation of three small test pits along the south edge of the north cloister walk to determine the extent to which archaeology might be a constraint on reconfiguring this awkwardly narrow and often slippery footpath (Keevill 2007). The results from test pit 1 would have a bearing on the main HTFE works, but the 2015 watching brief provided much better data, and the 2007 project needs no further consideration here.

The Dean and Chapter commissioned the Downland Partnership to undertake a point-cloud 3D survey of the Cathedral and the grounds immediately around it in 2006-7. This was not directly related to the emerging access project, but it did produce an extremely valuable 3D model as well as 2D drawings of the building, the cloister and other areas. For the first time, it was possible (indeed easy) to create and interrogate three-dimensional models of any part of the Cathedral, and thus appreciate how its spaces interacted – and might be improved. It is probably fair to say that this revolutionised Chapter’s (and their design team’s) vision of how the site might be improved, particularly for inclusive access, and with special emphasis on the crypt. The feasibility study progressed further in 2009-10, and the new survey was instrumental in the identification of the site in the south-east corner of the South Quire Aisle where, it was realised, one lift could operate between and provide access to both of the main floor levels in the Cathedral and the crypt beneath them. This was one of seven possible lift positions which were rigourously tested on a number of grounds, including archaeology, and it emerged as the favoured location because of the internal position and the unique ability to give one point of access to all three floors.

As noted, CFCE granted what amounted to a preliminary approval of HTFE as a whole in 2010, but reserved a determination on the crypt and lift access pending further feasibility and design work. This included an archaeological evaluation, in two stages. The first of these was to carry out a groundpenetrating radar survey of the entire crypt (Plate 4), and as much of the South Quire Aisle as could be achieved given the constraints imposed by the Kent Steps and the existing late 20th -century chair lift on their south side (GSB 2011). It had been hoped that the crypt survey would provide evidence for the east end of the Norman cathedral, but the results were disappointing – apparently due to the thickness and composition of the late 19th/early 20th -century concrete floor which was still in situ at the time. Modern services beneath the floor also affected the survey response. Fortunately results in the South Quire Aisle were better. At least three graves were clearly visible, and these matched precisely with existing ledger stones on the floor (though there is no certainty that these are genuinely in situ rather than relocated to these positions). The foundations of the south wall of the Norman cathedral were also located successfully, running east-west along the centre of the Aisle. Finally two large anomalies resembling the Norman south wall were located, one running south from it to the wall of the Aisle, and the second returning eastwards from this (Plate 5). It seemed possible that the north-south foundation at least might relate to the ‘lesser south tower’ (ie a smaller equivalent to the so-called Gundulf Tower on the north side of the Norman cathedral) postulated by Hope (1898, plate II). The full significance of these anomalies would become clearer when work on the lift shaft started in 2014, and is discussed in Chapter 6.

Time slice images of the GPR results from the South Quire Aisle, with provisional interpretation of features added in 2012. The anomaly identified as ‘Gundulf’s lesser tower’ probably relates to the Norman masonry found under the Kent Steps in 2014 - see Chapter 4.

The second stage of the evaluation comprised the excavation of seven small test pits in February 2012 (Keevill 2012). These were located to examine the building’s foundations at various points so that the project’s civil engineer could examine them, but all the pits were excavated under GK’s archaeological direction. Pit 10 was located in the two Norman bays on the west side of the crypt, while three (pits 5, 6 and 8) were in the main area between that and the Ithamar Chapel (underneath the Presbytery). One (pit 4) was in the vestry under the Chapter Library, ie off the south-east corner of the main crypt. The final two pits (1 and 3) were in the north cloister walk. As the pit numbers suggest, several planned pits were not dug. As with the 2007 work in the north cloister walk, the results from these pits were largely superseded by the much more extensive work in 2014-16, and they are only considered further where relevant in Chapters 4-6.

The various consents and approvals gained during 2012-13 meant that the project passed quickly into the detailed design, tender and procurement stages – but these would take more than a year to complete. HLF and other funders therefore agreed that various smaller elements of the project could proceed during 2013 in advance of the main contract. These were broadly described as enabling works – ie stand-alone items which would make the main work easier to accomplish. Alterations to the modern storage area on the west side of the North Transept had no archaeological implications. A new store would also be established for vestments and other items behind the high altar: this was a large timber box mounted over the Arundel Tomb, a fine monument dating to c 1400 with the indent for a memorial brass on its top. This was already inaccessible to the public, so the fact that the new store would hide the tomb was accepted subject, of course, to full protection of the tomb. A laser scan of the tomb was carried out in November 2013 to create a full 3D model of the monument (Edwards 2014). This is part of the project archive. Finally within the Cathedral, a dendrochronology survey was carried out on Chapter Library roof (Arnold and Howard 2013). This successfully dated timbers to 1342-63 and 1355-80. These felling date-ranges overlap, giving rise to the possibility that all timber was felled in a single operation in 1355-63. Alternatively, the slightly different felling date ranges may indicate the use of stockpiled timber, something which was not uncommon, especially amongst large and wealthy institutions such as cathedrals. Whether the roof was constructed in or soon after felling of timbers in 1355-63, or in 1355-80 utilising some stockpiled timber, the results point to it belonging to the same scheme of work (or one immediately succeeding it) as the magnificent doorway through which access to the Chapter Library is gained. The roof would undergo extensive conservation and repair work during 2015-16, and was the subject of a full archaeological building survey before this started (Jones 2015).

The main archaeological impact during the enabling works comprised much needed improvements to drainage and other service on the north side of the cathedral. A full archaeological watching brief was maintained during this work in July-August 2013. The limited exposures of archaeological remains during this stage are described briefly in Chapter 3.

Archaeology during the main contract

The excavations within the crypt and cloister garth were undertaken intermittently from September 2014 to January 2016. An archaeological presence was only required while ground-works trenching and larger scale ground reduction were being undertaken. A three-week period in 2014 saw the fulltime archaeological presence of a small team within the crypt to ensure that the large area then exposed within St Ithamar's Chapel and the area immediately to its west could be fully cleaned and recorded. A series of plans at a scale of 1:50 were drawn on site and then reduced for this report to a scale of 1:100. More detailed plans of specific areas were drawn at a scale of 1:20, with many sections drawn to the same scale. The positions of the latter are shown on the report plans where necessary. More than a thousand context numbers sheets were assigned and recorded during the course of the project. Tables 1 and 2 summarise these, firstly by geographical area and secondly in numerical order.

Useful artefactual dating evidence was sparse. Relatively few contexts produced pottery (the main source of dating). Only one coin was found, but again this did not help in understanding the structures and other stratigraphy. Our only useful source of dating was the stratigraphy itself - how structural elements related to each other and to adjacent layers. For a full context list arranged numerically see table 1 of the Archive Report.

The research agenda

HTFE would be a challenging project, of that there was no doubt, but archaeologically there was every hope that it would be a rewarding one. It covered some of the Cathedral’s most important historic spaces (inside and out), and in particular it offered a unique opportunity to investigate the whole of the crypt. This was the best (perhaps only) place to examine the form and layout of the first Norman cathedral’s east end – a vexed question in an academic debate which has endured at least since St John Hope’s seminal papers on the historic development of Rochester Cathedral (Hope 1898 and 1900). He wrote that he had found clear evidence that the eastern arm of Gundulf’s cathedral had a simple, straight end with a small square chamber extending east from its centre; there were no apses (Hope 1898, 203). Subsequent authors have refined or challenged various aspects of his analysis, but the greatest disagreement has generally been reserved for the east end. Most could not accept Hope’s claims for a squared-off east end, and promoted the apsidal concept in its place. The reconstruction of the eastern arm after the fire of 1179 had necessarily destroyed all trace of the earlier version (except that some of the burnt masonry seems to have been re-used in the new build): but the foundations of the first east end were likely to survive under the crypt floor. Indeed Hope claimed to have examined them by probing and excavation – hence his confidence in the model he put forward. What answer would HTFE hold? Chapter 2 explores some of the themes we hoped to address during HTFE, while Chapter 4 describes the fieldwork results in detail.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements Many people contributed greatly to this project, and we are grateful to acknowledge this. We hope we have not omitted anyone in the following list, and apologise profusely if we have. We are very grateful to:

• The Heritage Lottery Fund, Colyer-Fergusson Charitable Trust, Friends of Rochester Cathedral, Wolfson Foundation, Rochester Bridge Trust, The Headley Trust, Allchurches Trust, the Esme Fairburn Foundation, and a number of private donors for their generous support.

• Successive Deans of Rochester the Very Reverend Adrian Newman, Mark Beach and Philip Hesketh, all of whom were strong advocates of HTFE, including our archaeological work.

• Successive Chapter Clerks/executive directors of the Cathedral: Edwina Bell, Gilly Wilford and Simon Lace.

• Ian Stewart, then Cathedral Architect (for his friendship as well as his professional role), and his colleagues at Garden & Godfrey Architects, plus the many other members of the HTFE Project Team.

• All staff of the Cathedral, but especially Head Verger Colin Tolhurst and his staff (particularly Joseph Miler and Jacob Scott – the latter also contributed extensively to the archaeological fieldwork), Sue Malthouse (Estates Administrator and Secretary to the Cathedral’s Fabric Advisory Committee), Marilyn Tyler, Rob Trice and Jara Carter.

• Commissioners and staff of the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England, notably present and past officers Becky Clark, Maggie Goodall, Anne Locke and Allie Nickell.

• All members of Rochester’s Fabric Advisory Committee contributed hugely to the success of the archaeological project through their wisdom, advice and support, but the contributions of Julian Limentani (Chair), David Baker and Nicola Coldstream (both also CFCE Commissioners) were particularly important. David’s long archaeological experience and common sense were invaluable, especially during the difficult days concerning discoveries where the new access lift was due to be built.

• Peter Kendall of Historic England, whose steadfast professional and personal support were of immense importance throughout.

• Ron Baxter, Richard Halsey, John McNeill and Tim Tatton-Brown provided expertise and advice during consideration of how to proceed with the new access lift in light of the archaeological discoveries in its intended location.

• We also wish to thank all the specialists and organisations who contributed to the archaeology project, as listed in Chapter 1.

• Ellan Gray was the enabling works contractor in 2013; Buxtons were the contractor for the main works in 2014-16. We are very grateful to them both for their support and forebearance.

• Finally we are very grateful to site assistants Cathy Keevill and Adrian Murphy, and volunteers Jacob Scott, Malinda Henderson and Christine Hodge.

Keeping the Cathedral standing, warm, lit, beautiful and ready to receive worshippers and visitors is a never-ending task.