Limoges enamel tomb of Bishop Walter de Merton, 1277

/John Blair reconstructs the limoges enamel tomb of Bishop Walter de Merton, founder of Merton College, Oxford, before its defacement by iconoclasts and reconstruction as its current form in the seventeenth century. Featured in The Friends of Rochester Cathedral Annual Report for 1993-1994.

Walter de Merton, chancellor of England, founder of Merton College in Oxford and bishop of Rochester, died in 1277 and was buried in the north-east transept of his cathedral, nextto St. William's shrine'. The elaborate stone canopy of the tomb which his executors built for him survives in the centre of the north wall, but of the tomb itself not a trace remains in situ. It vanished in the Reformation period, and the present Victorian marble effigy is the latest of at least three replacements supplied by the grateful Fellows of Merton since the 15905?. The original tomb may have been unique in England at its date, and its loss is a direct result of its exotic and unusual character: it was made almost completely of enamelled copper, vulnerable and tempting.

Luckily, there are three sources which together allow a precise and reliable reconstruction of this unusual monument. First, the original executors' accounts indicate its source and general character. Secondly, eighteenth-century drawings record a series of comparable tombs which survived in various French cathedrals and abbeys until the Revolution. And thirdly, a marble slab long visible in Rochester cathedral can now be identified as the one stone component of the Merton tomb, proving its close similarity to the tombs shown in the French drawings.

The tomb and its associated expenses have their own section in the executors' accounts', which may be summarised as follows:

To Master Jean, burgess of Limoges, for the making of the tomb and its carriage from Limoges: £40 5s. 6d.

To one of the executors going to Limoges for overseeing and arranging (ad ordinandum et providendum) the making of the tomb: £2 6s. 8d.

To a boy for going to Limoges to fetch the tomb on completion and bring it with Master Jean to Rochester: 10s. 8d.

For masonry (mazoneria) around the tomb: £22.

For ironwork of the same, and the carriage of the same from London to Rochester, and other preparation at the said tomb: £4 13s. 4d.

To a glazier for the glass of the windows bought next the tomb (emptarum iuxta tumbam): 11s.

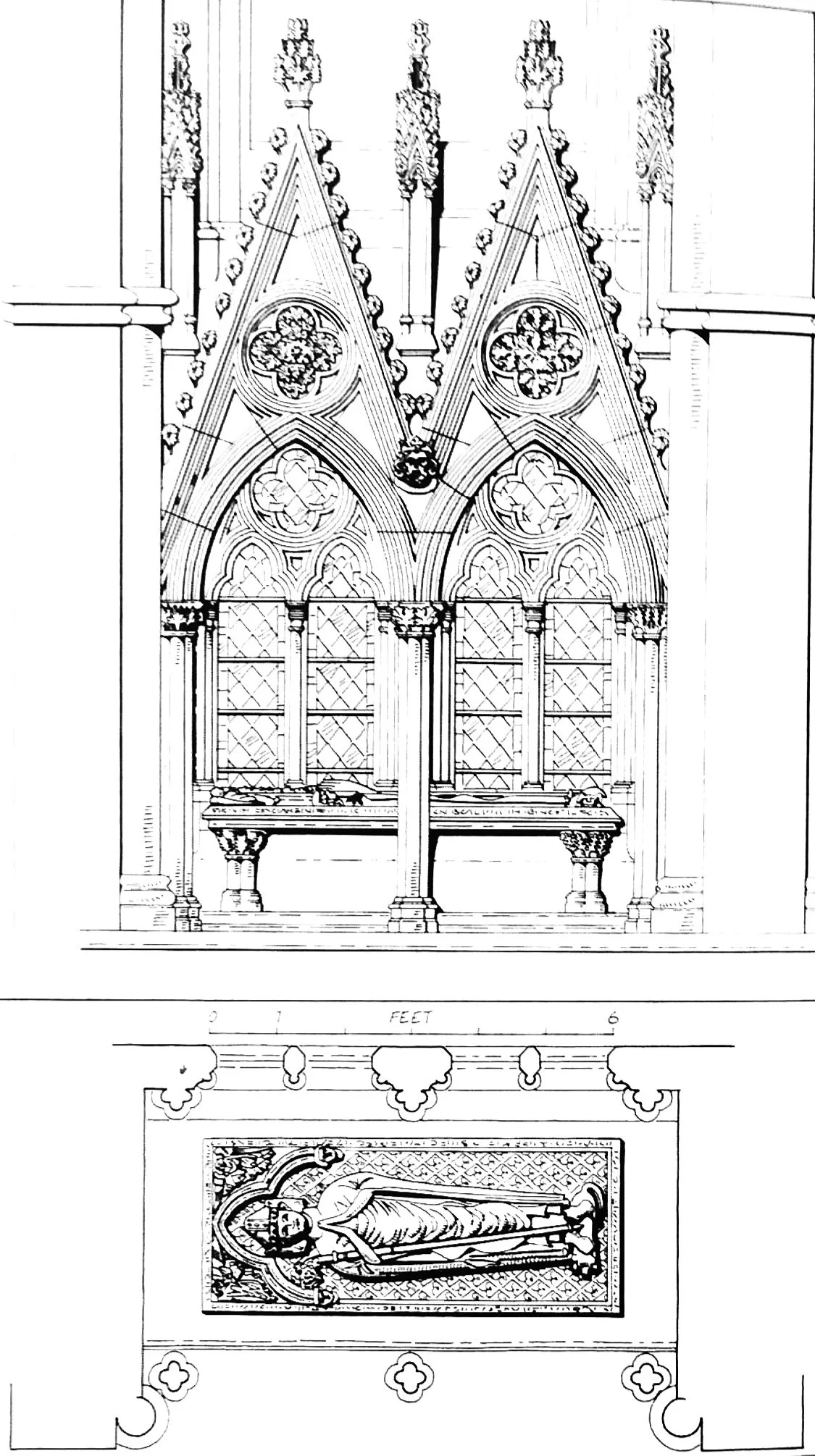

Immediately identifiable is the surviving stone canopy (Fig. 1), the 'masonry around the tomb', ordered from one of the London tomb workshops at the plausible enough cost of £22. The windows, too, are clearly the four cusped lancets which are integral with the back of the tomb-recess, though no medieval glass now remains in them. The other payments concern an expensive and unusual monument bought from a master-craftsman of Limoges, who needed briefing at an early stage by one of the executors and then had to come in person to assemble his work in the cathedral. There is only one kind of product that the executors would have sought so far afield as Limoges: a work in the enamelled copper for which that city had been famous for generations.

In the thirteenth century effigial tombs of cast and gilded copper-alloy were a top-level fashion throughout Europe, represented in England by the lost monuments of bishops Jocelin (d.1242) and William Bitton I (d. 1264) at Wells and Robert Grosseteste (d.1253) at Lincoln, and by the surviving effigies of Henry IlI and Eleanor of Castile (made in the 1290s) in Westminster Abbey*. It was an obvious step for the Limoges workshops, with their huge trade in enamelled copper candlesticks and other portable items, to make full-scale tombs for the religious and secular artistocracy of France. The genre is represented today by the effigies of Blanche de Champagne (d. 1285) now in the Louvre and of William de Valence (d. 1296) in Westminster Abbey, consisting of sumptuously enamelled sheets of raised copper attached to a wooden core and mounted on a base-plate. Only a year before Walter de Merton's death an enamelled tomb for Thibault VI, count of Champagne, was ordered from Master jean de Chatelas, burgess of Limoges", exotic and unusual character: it was made almost completely of enamelled copper, vulnerable and tempting.

In the thirteenth century effigial tombs of cast and gilded copper-alloy were a top-level fashion throughout Europe, represented in England by the lost monuments of bishops Jocelin (d.1242) and William Bitton I (d.1264) at Wells and Robert Grosseteste (d. 1253) at Lincoln, and by the surviving effigies of Henry IlI and Eleanor of Castile (made in the 1290s) in Westminster Abbey*. It was an obvious step for the Limoges workshops, with their huge trade in enamelled copper candlesticks and other portable items, to make full -scale tombs for the religious and secular artistocracy of France. The genre is represented today by the effigies Of Blanche de Champagne (d. 1285) now in the Louvre and of William de Valence (d. 1296) in Westminster Abbey, consisting of sumptuously enamelled sheets of raised copper attached to a wooden core and mounted on a base-plate. Only a year before Walter de Merton's death an enamelled tomb for Thibault VI, count of Champagne, was ordered from Master jean de Chatelas, burgess of Limoges'.

Fig. 1: Walter de Merton's tomb: the surviving canopy, with a reconstruction of the Limoges enamel monument inside it based on the surviving slab and the French analogies. (Artist's impression drawn by John Atherton Bowen MAAIS Jan 1994).

who sounds as though he may have been the same 'Master Jean' chosen by Walter's executors. So far as we know, Walter was unique among English bishops in having a Limoges tomb°, and the Valence effigy is the only other which is known to have existed in England.

Analogies for the Rochester tomb must therefore be sought across the Channel.

The early eighteenth-century drawings of Roger de Gaignières include several tombs with full-size metal effigies. Many were doubtless cast in copper-alloy, but a few examples with richly patterned surfaces, and said to be made of 'cuivre esmaille', can plausibly be identified as Limoges products?, Together with the surviving Valence and Champagne effigies they suggest the likely form of Walter's tomb (Fig. 1): the bishop in his vestments, his feet on a beast and his head on a cushion probably flanked by angels, these relief components being attached to a base-plate of diapered and enamelled copper.

At least four of the metal effigies recorded by Gaignières" had a feature which, for reasons which will be explained shortly, is especially relevant to the Rochester tomb: the slab bearing the effigy was raised up like a table-top on short colonettes.

Bishops Eudes de Sully (d. 1208) at Paris and Jean de Melun (d. 1257) at the abbey of Jard each had four colonettes with capitals (foliated at Jard) and bases. On the exceptionally lavish retrospective monument of the Emperor Charles the Bald (d.877) at Saint-Denis the colonettes were double, and topped by crouching lions Nearest in date to Rochester, and undoubtedly of enamelled copper, was the effigy of Bishop Guillaume Roland (d.1260) at Notre-Dame de Champagne, which rested on a set of six plain, stubby columns.

The link between these French tombs and Rochester is provided by a battered slab of Purbeck marble (Fig. 2) which now rests on modern blocks of stone in the recess to the west of the Merton tomb-canopy. Formerly it lay face-down in the paving of the north-east transept floor, and it has usually been identified as a fragment of St. William's shrine. However, Walter de Merton's tomb stood nearby, so it is just as likely that a slab left over after the removal of its metal parts was used to pave the vacant site of the shrine. Close inspection shows that this inference is almost certainlv correct.

The slab originally measured 190 by 79cm, and is 10.5cm thick. The edge is moulded with a small hollow-and-fillet below a chamfer on the upper arris. Cut into the upper surface are two pairs of Y-shaped channels, flat-bottomed and shallow, which at one end are arranged so as to point diagonally inwards from the corners, and at the other point straight towards each other from the sides of the slab. On the under-surface are a series (presumably six, though three of them are hidden by the modern supports) of incised features, not quite identical but each taking the basic form of incised lines radiating from a centre and describing a circle or polygon some 20cm across.

The flat recesses resemble the channels, ubiquitous on the slabs of early fourteenth-century brasses, which received bars soldered across the backs of joints between plates; they show that the slab had some kind of complex metal structure fixed to its upper surface°. Likewise, the only possible interpretation of the incised features on the lower surface is that they are scorings to key mortar or lead for attaching the tops of six columns. Here then is a slab, thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century to judge from its moulding, which had metalwork fixed to its surface, which rested on columns, and which was re-used in the pavement only a few feet away from Walter de Merton's tomb: it can hardly be doubted that what supported was Walter's Limoges enamel effigy.

Fig. 2: Purbeck marble slab in the north-easttransept of Rochester Cathedral, interpreted as the remains of Walter de Merton's tomb.

The channels make good sense in terms of bars fixed under the base-plate to secure the main relief components at either end: the diagonal pair for the angels flanking the bishop's head, the horizontal pair for the beast under his feet. That the slab is of Purbeck marble rather than French stone need cause no problems. The London marblers were expert in producing components for assembly into larger works, and the f1 or £2 which the slab might have cost at contemporary prices is presumably included in the £22 paid for 'masonry' from London. Fitting the chamfered edge of the base-plate (which could well have carried the inscription) over the edge of the marble slab would have needed careful measurement, and was presumably one of the matters which the executor discussed in Limoges with Master Jean.

3D model of the marble slab in the North Quire Transept thought to have held the limoges effigy.

It cannot be proved that the colonettes of the Merton tomb were of metal rather than stone, but gilt brass or enamelled copper would be consistent with the aesthetic of colour-contrasts and glittering surfaces. This inference is strengthened by the monuments of two wealthy men who must have known Walter de Merton.

The tomb of Peter de Aigueblanche, bishop of Hereford (d. 1268), formerly at Aiguebelle in Savoy, comprised a cast-metal effigy (evidently the work of a German founder) on a slab supported by six metal columns12. In York Minster Dean William de Langton (d. 1279), a nephew of Archbishop Walter de Grey, had a cast-metal effigy with 'brass' base-plate, resting on a grey marble slab raised on six 'brass' columns'3. Here the metal parts were probably again of north German or Flemish make, whereas the slab had an inscription in Yorkshire or Lincolnshire lettering and was almost certainly local: the method of ordering and assembling this monument followed the pattern set a year or two earlier at Rochester. The context of Walter de Merton's remarkable tomb was a Continental fashion which seems to have enjoyed a brief popularity in the later thirteenth century among the magnates of the English Church'4,

John Blair

References

W. H. St. J. Hope, The Architectural History of the Cathedral Church of St. Andrew at Rochester (1900),

Ibid. 126. The monument supplied in 1598-9 is described in Registrum Annalium Collegii Mertonensis

1567-1603, ed. J. M. Fletcher (Oxford Historical Soc. n.s. xxiv, 1976), 332, 337.

The Early Rolls of Merton College, Oxford, ed. J. R. L. Highfield (Oxford Hist. Soc. n.s. xvii, 1964), 137.

N. Rogers, 'English Episcopal Monuments 1270-1350', in J. Coales (ed.), The Earliest English Brasses:

Patronage, Style and Workshops 1270-1350 (1987), 20-2.

M.-M. Gauthier, Émaux Limousins Champlevés des XIle, XIlle et X/Ve Siècles (Paris, 1950), 55, 25.

Rogers, 'English Episcopal Monuments', 19.

'Les Tombeaux de la Collection Gaignières', eds. J. Adhémar and G. Dordor, Gazette des Beaux-Arts Ixxxiv (1974), 3-192, Ixxxviii (1976), 3-88, x (1977), 3-76; see also Rogers, 'English Episcopal Monuments', 19 and Fig. 7.

"Tombeaux', Nos. 55, 254, 256, 267.

Hope, Architectural History, 128-9.

Compare the marks remaining on the Grosseteste tomb at Lincoln after the loss of its metal effigy: Rogers,

'English Episcopal Monuments', 20.

J. Blair, 'English Monumental Brasses before 1350: Types, Patterns and Workshops', in Coales (ed.), Earliest English Brasses, 144.

Rogers, 'English Episcopal Monuments', 21-3.

S. Badham, 'A Lost Bronze Effigy of 1279 from York Minister', Antiquaries Journal, Ix (1980), 59-65.

I am very grateful to Tim Tatton-Brown for his help during the preparation of this paper.