Choir stalls and associated furniture, 13th century

/Charles Tracy studies the exceptional early thirteenth century choir stalls and associated timber furniture, with drawings and carpentry notes by Cecil Hewett. Featured in The Friends of Rochester Cathedral Annual Report for 1994-1995.

The Choir-Stalls

The survival of choir-stalls before the fourteenth century in Northern Europe is a great rarity. In Germany there are some twelfth-century seats at Ratzeburg near Lübeck (PI.I). Such survivors from the Early-Gothic period as there were by the eighteenth century in France, Belgium and Germany were either replaced with Baroque furniture, or finally succumbed to the depredations of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods. Some of the fine early thirteenth-century choir-stalls from Lausanne Cathedral' still huddle inappropriately and uncertainly in the south nave aisle of that building. In France one can only point to the mid thirteenth-century choir-stalls in the small abbey church of Notra Dame de la Roche, Le Mensil St. Denis, a few miles south of Paris.? In England a complete set of choir-stalls of this period survives at Salisbury Cathedral,' and three oak columns with stiff-leaf foliage, possibly from an early-Gothic set of choir-stalls at Peterborough Abbey.[1]

A complete set of choir-stalls, albeitt of almost entirely nineteenth century workmanship, and dating from as early as c. 1227, is found at Rochester Cathedral (PI.I).

Rochester Cathedral. View of S. side of choir in 2023.

The furniture can be dated precisely, as this is the date of the introitus in novem chorum, noted in the cathedral records. It was reconstructed, apparently according to the original design, under the supervision of George Gilbert Scott in 1872, having undergone various transformations during the previous three hundred or more years. In 1541 the forms were enclosed by new desks, the linenfold panels of which are still extant.[2]

PI III* Rochester Cathedral. Detail of mid 16th century choir-stall desk panelling, south side.

Rochester Cathedral. Pew ends north and south side of choir from Gilbert Scott's 1872 restoration. Note 6.

The stalls survived the Civil War unscathed,® and probably remained unaltered until 1742/3, when 'Very considerable alterations and improvements were made in the choir in the years 1742 and 1743, under the direction of Mr Sloane. New stalls and pews were erected, the partition walls wainscotted and the pavement laid with Bremen and Portland stone. The choir was also newly furnished... Most of this refurbishment was removed by L. N. Cottingham in 1825-26, when new stalls and canopies designed by Edward Blore were erected. When Gilbert Scott restored the cathedral much of the original work was found to be still remaining under the recent accretions. A description of these, and an account of the restoration work was given by Baker King in 1874 as follows:

'Upon the removal of the wooden pews, the lower part of the ancient stallwork (PI.IV) on the north and south sides of the choir were found to be tolerably complete, and the whole design and detail of the upper part, with the exception of the capping, could be made out from fragments which were discovered. The arrangement consisted of one row of stalls on each side of the choir, with their desks. Each side had two gangways, dividing the desks into three lengths. No portions of the returned stalls nor of their platforms remained.

PI IV Rochester Cathedral. Thirteenth century choir-stalls on north side.

The platforms or wooden floors were of unusual width, having 4 g projection The front cill of the platform rested on the ancient stone plinth, 7'5" deep. The front oil di the plation rested on the benacen the seal, and boses, having a roll moulding on the top angle. The whole of the floor and plinth a been raised 10° or 11° and the plinth and joists were resting on modern brickwork.

The stalls had been divided, not by elbows rising from the floor in the usia way, but by divisions above the seat-level, tenoned into brackets about 3 wide, which project from, and are framed into the continuous cill next the wall level with the top of the seats. The brackets and back cill were rebated for the seas and there were marks for hinges but no portions of the misericords below.

The seats had been very low, only 13.5" from the floor, but the stall divisions were 2' 1" in height above the seat. The addition of a capping of 4" in thickness makes the total height a little more than 3' 6", the ordinary heights of stalls.

By removing the brickwork, and lowering the bottom of the stone plinth to the level of the choir floor, the stall capping fits exactly to the line of the old painted decoration of the side walls. The stone plinth remains, but is now concealed by the floor of the next grade of seats.

The desks were nearly perfect, they have merely been repaired, and have had two or three missing shafts supplied. The wooden screen, upon removal of the deal canopies was found and had only one ancient door post, that on the southern side, and this was much mutilated.

Fragment of carving on south side of choir door.

At about the level of the springing of the small arches are slight remains of the figure of an angel, which appears to have stood on a corbel with a cresting of foliage, the whole carved in the solid with the post Rather lower, on the eastern face of the post, was a mortice, but there was no further indication of the further design of this portion. The north door post had been replaced by a post of fir. The old top beam remained throughout the length of the screen, the part over the doorway being stop-chamfered, and having remains of painting. There were no mortices for arched ribs, and it was evident that the old entrance had been square in form.

The upper panels were originally open, the boarding having been introduced during the late fitting of the choir.

The decoration found on the desk fronts remains untouched, as does a considerable portion of the lower part of the wall painting'.[10]

Surviving C13th painted decoration of the choir stalls.

The above passage is an invaluable first-hand account of the condition of the furniture when it was rediscovered, and of the subsequent restoration. The fort of the stalls, which we know to be authentic, is of great interest because it 005 not conform to the pattern established in later monuments. The seat standards do not rest directly on the ground but sit on brackets tenoned into the seat rail.

This conformation is reminiscent of the way a stone sedilia can sit on a projecting ledge, leaving the bottom section slightly undercut. But even the choir-stalls, Ratzeburg have standards which rest on the ground. Little of the restored monument is ancient. The seat rail survives in many parts, as does the underside of the projecting brackets. A single ancient example of the column that fronts the seat standards survives in the north-east corner.

Rochester Cathedral. Original column in front of stall standard in north east corner of back-stalls.

It is unlikely that there were ever any substalls at Rochester, this probably being the rule for monastic churches. There were sixty seats, a comparable number io monastic Peterborough and Westminster abbeys.'

The desks on each of the long, sides each consist of a series of trefoiled arches carried by slender octagonal shafts with stout ones at the ends, and supporting a thick slab of oak (Fig. 2). As the top of this is only 55.7 cm from the platform on which it rests, it is unlikely that these desks would have been used for books. Hope remarks that monks used none, and suggests that they were for the brethren to rest their elbows on when they were Kneeling. 'prostrati super formas' during certain parts of the services'2. Similar uprights and roll mouldings are found on the seating, and the arcading of the pulpitum. The style is of plate tracery, fictively pierced on the arcades of the desks. The roll moulding underneath the bracket supporting the standards is emphasized at the sides by undercutting, giving the impression of a Romanesque billet.

It is difficult to find anything stylistically comparable to this furniture. Columns in the architecture of this period were usually rounded, yet here they are polygonal. On the desks there are paired columns occur every so often linked by an arch device surmounted by a sort of coping. This is somewhat reminiscent of a Romanesque corbel. But the most characteristic feature of the Rochester woodwork is the way, in the arcading of the pulpitum and the desks, the uprights are carried through to the cornice, terminating in another moulded capital." This second column is halved so that it tenons into the top of the capital along with the horizontal plank that forms the spandrels of the arches. It does not seem to fill any constructive purpose, and one only can suppose that the designer was looking to such systems of 'linkage' found in the triforia of French High Gothic churches such as Amiens.

The solid wall behind the single row of monastic stalls on each side of the choir, as well as the lower portion of the choir screen, was evidently decorated with a single background design. The lions and fleurs de lys, with flower and interlaced ribbon work borders, which are there now are a copy of a scheme devised sometime shortly before 1340."* Evidence of a thirteenth-century painting scheme was found by Scott at the back of the prior's stall on the south side of the choir entranceway, where it must have been preserved by the addition of a canopy at the time of the fourteenth-century repainting (back cover) The design here, painted on oak boards, was described by one writer as 'resembling a rough copy of some Scottish tartan' 15 One could speculate, perhaps, whether this unusual design could have had anything to do with the source of the funds to rebuild the choir. Rochester reaped a considerable bonanza from the offerings at the shrine of William, the Scottish baker converted into a local saint and martyr by carefully orchestrated publicity. I The funds accruing from this exercise subsidised the building of the sacrist William de Hoo's new choir and its furnishings.!?

In Northern Europe in the thirteenth century it is probable that most choir-stalls like those at Rochester, had no superstructure at all. 18 Massive stone parclose walls, again as at Rochester and also in Prior Conrad's choir at Canterbury Cathedral, " provided shelter from draughts, and ensured that the daily offices were undisturbed by visiting pilgrims. At Rochester the choir is contained in the eastern arm of the church, following the precedent set in the early twelfth century by Christchurch, Canterbury. In all of the Norman greater churches in England the ritual choir had been either wholly in the nave or astride the crossing. The parclose walls at Rochester are nearly six feet thick, and are presumed to be adopted from Bishop Gundolph's eleventh-century presbytery.20 Enclosing walls were sometimes frescoed or sculpted,2' but, if not on feast-days they were often decorated with tapestries. Hope's suggestion that at Rochester the Bishop and prior's stall may originally have had canopies is somewhat surprising. 2 The evidence adduced was the fragment of sculpture on the north side of the bishop's stall on the south side of the entranceway, on the level of the wooden panelling arcade (P1.VIII). This seems to be drapery, and it may have been part of a cloak curling up at the hem into a ' Stiff-Leaf'. But from its position and the scale of the figure, the sculpture would hardly have been part of a canopy, but rather one of perhaps a pair of figures supported on corbels flanking the entranceway. The main formal stress at Rochester is the combination of woodwork at floor level with a flat area of painted decoration above. The thirteenth-century decoration was painted on panelling behind the return stalls, and would surely not have been there if there had been canopies.23

The fragment of thirteenth-century decoration from behind the stalls at Rochester is rare enough. In addition, the painted desks or forms at ground level are unique for Northern Europe. The comprehensive painted decoration of choir-stalls in this way is likely to have been indulged in only occasionally. The desks are remarkably well preserved largely because, from the sixteenth century, they were encased inside post-medieval woodwork.24 The decoration is painted over a layer of plaster or white lead. The mouldings are picked out in vermilion, green and yellow, small panels which occur at intervals between the shafts being painted green, and the spandrels of the arches decorated with small single lights and also round windows, painted in black'.[12]

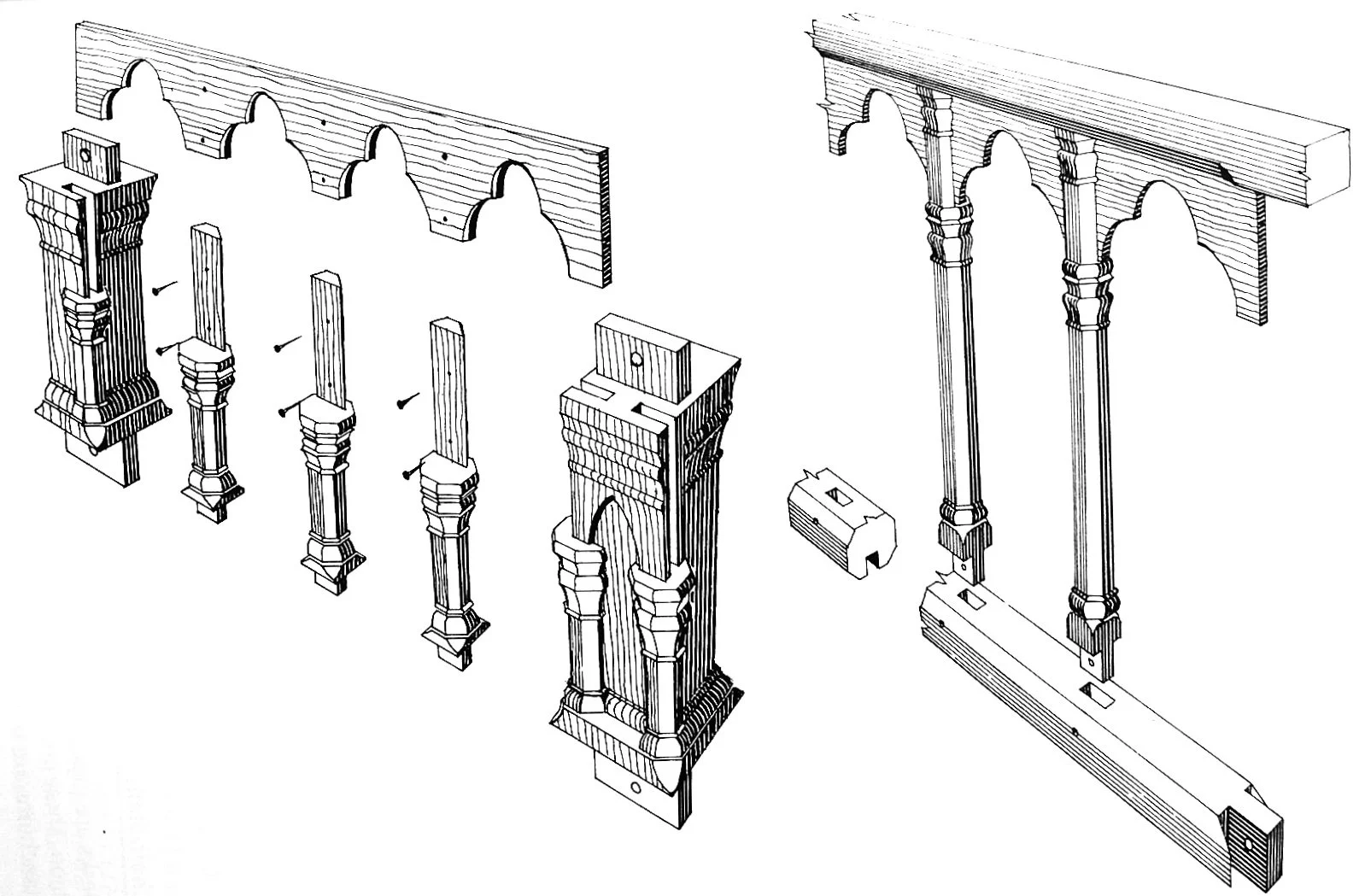

Carpentry notes by Cecil Hewitt

The desks are grouped into four and five bay widths. At each end is a stanchion. These are tenoned into the 'platform' or plate, and the top cill. Between two stanchions are mortises for the freestanding colonnettes. These are halved for the planks, which are carved into four trefoiled arcades and chamfered. The planks were nailed on to the halved colonnettes with two thin nails. This was done on a bench. Then the whole group was pushed into the mortises, and the top sill was added and pegged into the two stanchions. The arches are painted in the original red, white and green.

Perspective and 'exploded' view of choir forms (copyright Cecil Hewett).

The wooden choir-screen has seven trefoiled arches between its ends and the doorway, and was mutilated in early times. The pilasters at the top are rebated through the plank and tenoned into the top and bottom rails. The arcading was open originally. The bottom rail is chamfered into an octagonal shape, as shown, and is chase mortised through the bottom end.

The 'Vestry'

The oak 'vestry' in the south aisle, and just east of the steps down to the crypt, also deserves consideration in this context. It is close in style to the choir furniture and must be part of the same campaign. It has been fitted in above the entrance to the crypt, adjacent to the steps leading towards the south east transept.26 Its entrance is from the south east transept.

3D model of the exterior of the choir vestry screens in 2020.

Although there are no motival comparisons with the joinery of the choir-screen and the choir desks, the similarity of the mouldings and the use of faceted uprights is proof enough of their contemporaneity.[27] lt is also interesting to note that the 'vestry' screens were also originally painted. On the boarding of the north-south screen are the remains of the original decoration of the stars.

We do not know if the present function is authentically medieval in origin. In medieval greater churches vestries are rarely mentioned, although at Durham for example The Rites mentions a 'revestry', also in the south choir aisle. The existing door into the 'vestry' at Rochester has been dated around 1300, when it is thought, the south transept was completely reconstructed. Both western walls of the south transept and the doorcase into the 'vestry' are of this date.

There must have always been an access door here as it was the only point of entry. Given its inconspicuous and convenient position, the space delineated by our wooden parclose screen is perhaps more likely to have been used aed vestry than anything else. in any case, the Rochester structure is an unique survival for its period in England.

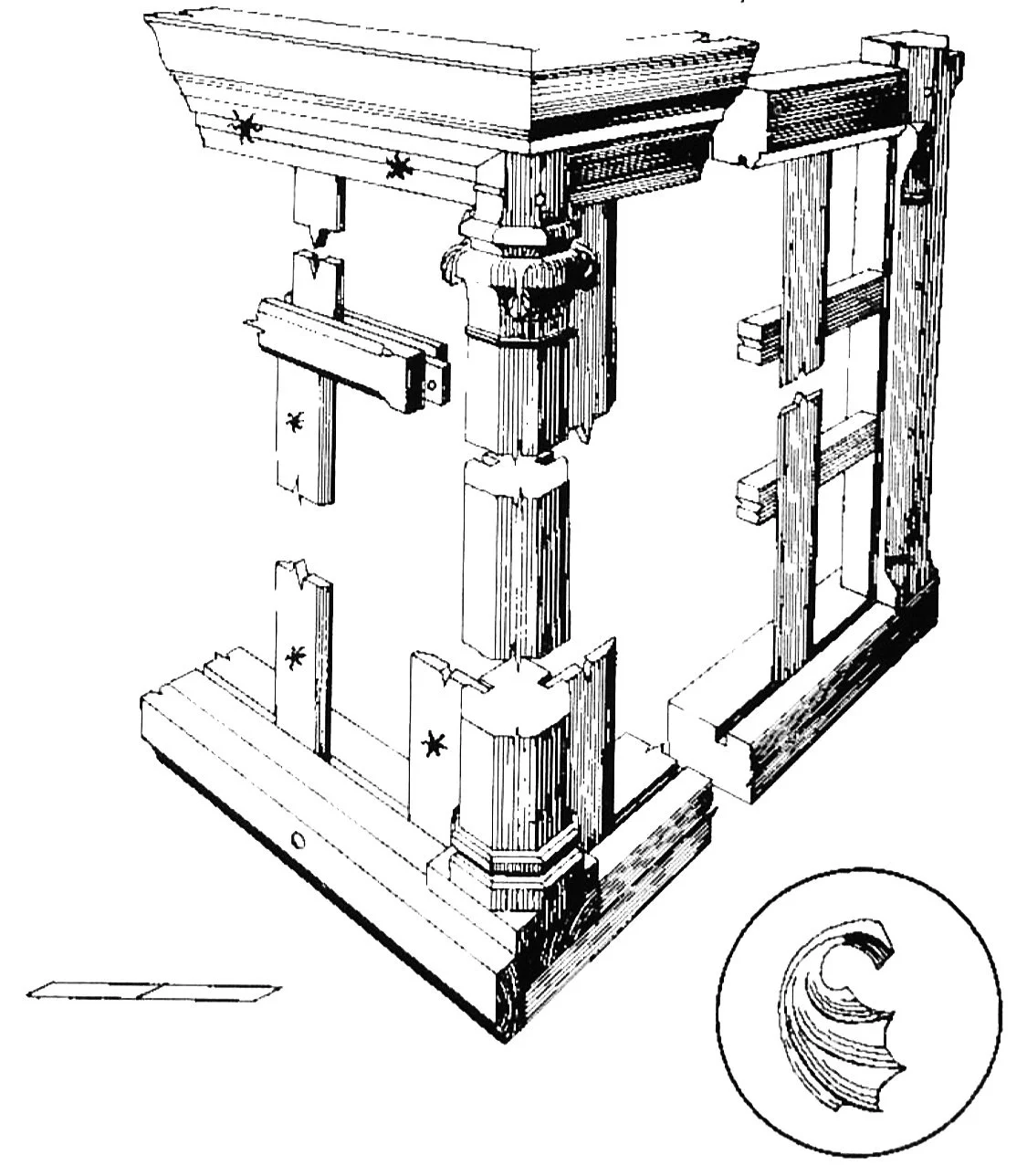

Carpentry notes by Cecil Hewitt

The structure consists of two wooden walls and three posts, being inside 121 7" long on the west, 10' 6" long on the south, 8' high and 7' 5" thick. It has an oak frame with vertical oak boards, having vertical splayed ends (Fig. 3). These are also used in the thirteenth-century Wells Cathedral cope chest, which also has the same vertical boards (Cecil Hewett, English Medieval Cope Chests, JBAA, CXLI, 1988, 108-11).

The 'vestry' was made in the carpenter's workshop, but not pegged. It would have been put together and pegged on site. The frame has three rails, being mortised and tenoned into the three posts. These rails have chased-mortises to hold the boards. The central post has a carved capital and base, and an octagonal shaft. It has carved into three 'leaves', as shown. It was built from the north post, the boards being put into the base chase-mortises, and the two rails were then pegged into the wall post. The top rail was pegged on the same post. Then the middle post was fitted and pegged, and the south wall fitted in the same way.

Perspective and 'exploded' view of part of choir vestry (copyright Cecil Hewett).

The last post is 6" from the stone arch, and the gap is covered by an original vertical board. This is painted red with dark blue stars.

The choir desks and screen and the 'vestry' are all chase-mortised, and could have been made by the same carpenter, who was using a rare plane. These boards would have been bought-in, not made on site, and were probably made by watermill, and obtained from London.

Conclusion

Rochester Cathedral posseses the remnants of the earliest complete suite of medieval choir furniture, designed for a greater church, in Northern Europe.

Not only can it boast an unique 'vestry' structure, but also it still bears the evidence of an elaborate painted decorative scheme on the stall backs, and, again uniquely, on the desks or forms placed in front of the stalls.29 Full credit should be given to George Gilbert Scott and his colleagues for the preservation and 'restoration' of this important landmark in the history of ecclesiastical furniture history.

Postscript

A historiography of the Rochester Cathedral choir-stalls would not be complete without a brief reference to the controversy over the origins of the fragmentary furniture at Barming Church, near Maidstone. In June 1939 Dr. Francis Eeles, then secretary to the General Council for the Care of Churches tried to claim that the Barming woodwork had been stolen from Rochester Cathedral. 'I should like to see Barming show its loyalty to the Bishop and Dean of Rochester by giving them back', he said at the annual festival of the Friends of Rochester Cathedral. The Bishop agreed with him. However, Barming parishioners were indignant. "It is not a question of loyalty to the Bishop and Dean", said the rector to an Evening Standard reporter. "The stall-ends did not come from Rochester Cathedral in the first place. They were presented to Barming Church (in 1871) by two brothers, named Beaumont, farmers in the parish. They went to Flanders for a holiday, saw the stall-ends in a shop, bought them and presented them to the then Rector of Barming, Mr Carr™' 30

In a retraction, published in The Times newspaper on 24 June, Dr. Eeles hastened to withdraw any suggestion that the Barming stall-ends had come from Rochester Cathedral'. The writer added: 'beneath the stalls of Rochester Cathedral are remains of massive thirteenth-century work, little seen and known, the survivors of drastic alterations. It was not unnatural to assume that these wonderful Barming stall ends formed part of that scheme. Rochester would be really the only reasonable possible local source. The definite evidence provided by Mr Sharp (the then Rector of Barming) now seems to make it safe to assume a Flemish or neighbouring origin'.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Dean and Chapter for giving me full and free access to the furniture for the purpose of research, and for allowing me to take the photographs with which to illustrate this paper. My thanks also to John Melhuish for helping with some of the plates, and seeing the article to the printers, and to others for assistance in small but important ways.

Notes

E. Bach, Les stalles gothiques de Lausanne, Zurich, 1929.

The abbey was placed under the rule of the regular Augustinians in 1226. The roof timbers of choir and nave are reported to have been dated by dendrochronology to 1232-50. For a 19th c. description of this furniture, see Auguste Moutie, Cartulaire de l'Abbave de Notre-Dame de la Roche, Paris, 1862.

The seats at Hastieres and Gendron-Celles in Belgium are of the 13th c.

Manufactured c.1245, see C. Tracy, English Gothic Choir-Stalls. 1200-1400,

Woodridge, 1987, 5-7 and Pls 12-25.

Whatever was the original purpose of these columns, the stylistic similarity of their capitals with those on the cathedral west-front at Peterborough is undeniable Peers suggested that the west-front may have been ready for consecration before

1238. See C. R. Peers, VCH, Northants, II, 1906, 444. Illustrated in Tracy (1987 PI. 6.

w. St. John Hope, The Architectural History of the Church and Monastery of St. Andrew, Rochester, London, 1900.

The firm of joiners used for the re-construction, and the fine new work, was Heaton, Butler and Bayne of Covent Garden, London.

Hope (1900), 108.

.. the Seats and Stalls of the Quire escaped breaking down, . .. Mercurius Rusticus, London, 1685, 135.

The words of a Mr. Denne, quoted by St. John Hope (1900), above, 108. This arrangement was illustrated in J. Storer, History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Churches of Great Britain, London, 1819, PI. 7.

C. R. Baker King, 'Choir fittings in Rochester Cathedral', Spring Gardens Note Book, 1875, ii, 75.

Peterborough had 70 seats, and Westminster Abbey had 66.

Hope (1900), above, 110.

On the desks the same device is employed but there is no second capital.

Hope (1900), above, 111, and S. Robertson, 'On a wall-painting in Rochester Cathedral Choir', Archaeologia Cantiana, X, 1876.

R. C. Hussey in Robertson (1876), above. A similar, but historiated, arrangement to that on the return-stalls at Rochester must have existed behind the twelfth-century stalls at Peterborough Abbey. See S. Gunton, History of the Church of Peterborough, London, 1686, 334.

See Anon, The History and Antiquities of Rochester Cathedral, Rochester, c.

1800, 10.

Hope (1900), above, 52.

There are so few French extant 13th c.choir-stalls that it is impossible to make any generalisations about France, beyond noting that there was no superstructure at Notre Dame, Paris.

See the monk Gervase's description of Prior Conrad choir at Canterbury Cathedral in W. Stubbs, The Historical Works of Gervase of Canterbury, London, 1879, 1, 12.

Hope (1900), 52.

Dorothy Gillerman, The cloture of Notre Dame and its role in the fourteenth century choir program, (Ph. D. dissertation: Harvard University, 1973), New York London, 1977.

Hope (1900), 110. He suggested that the bishop's throne at the eastern end of the south lateral stalls was not set up before the early fourteenth century by Bishop Hamo of Hythe (1319-52).

The oak double-columns at Peterborough, nearly 2.5m. high, which were made up into a sedilia in the 17th c., may have been the uprights of Abbot Walter's choir-stalls, c.1240.

Hope (1900), 110-11.

E. W. Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting. The Thirteenth Century, Oxford, 1950, 593 and Supplementary PI. 47a.

The planking of the east-west section is modern, as is that along the top section of the north-south portion and the battens hiding the joins. Also the cornice is modern throughout.

The central upright of the vestry has the only crocket capital to appear on any of the woodwork.

J. T. Fowler (ed.), The Rites of Durham, Surtees Society, CVII, 22.

In southern Europe, Spain possesses examples of painted choir-stalls of the 12th

c. See M. Carmé Farré Sanperra, El Museo de Arte de Cataluna, Barcelona, 1983,

40-41. There is also a description and illustration of the stalls in Joseph Mainar, El Moble Caltala, Barcelona, 1976, 14-18

Evening Standard, 16 June, 1939.

Featured in The Friends of Rochester Cathedral Annual Report for 2019.

Friends of Rochester Cathedral Annual Reports

The Friends of Rochester Cathedral were founded to help finance the maintenance of the fabric and grounds. The Friends’ annual reports have become a trove of articles on the fabric and history of the cathedral.